Changing the Baseline Could Mean an Extra Trillion in Debt

Republicans and Democrats do not agree on much, but both parties are talking about business tax reform that is "revenue-neutral," raising the same amount of money as the current tax code. But "revenue-neutral" can mean drastically different things, depending on which baseline policymakers choose to use. Discussing budget baselines might put most people to sleep, but the choice could mean an extra trillion dollars added to the debt over the next ten years.

Playing Baseline Games

Much of the disagreement over which baseline to use focuses on tax extenders, a set of mostly business tax breaks that expired in 2013. These breaks expire every year or two, and Congress routinely extends almost all of them. The Senate Finance Committee has a bill that would extend nearly all of them for two years, at a cost of $85 billion. Yet if all those provisions are extended year after year, the total ten-year cost would be almost $700 billion. Although Congress will likely deal with the extenders before the end of the year, their fate could set the parameters for future tax reform efforts.

Unfortunately, House Budget Chairman Paul Ryan (R-WI) is proposing to lower the bar for revenue-neutrality. He recently suggested policymakers should make some of the tax extenders permanent during the lame duck session, arguing that they do not need to be paid for and should add to the debt (which makes their costs disappear from the budget process and from needing to be offset in a revenue-neutral tax reform). If these were made a permanent part of the tax code, a future "revenue-neutral tax reform" would raise $700 billion less than before. Essentially, he is suggesting that this Congress lock in lower revenue levels – and higher debt – to make it easier for the next Congress to pass tax reform that they can claim is revenue-neutral.

This plan would increase the debt by $700 billion over the next ten years, but it could be much worse if Congress takes an even more reckless approach to the extenders. For instance, the Ways & Means Committee has proposed expanding the provisions and enacting new breaks. Their package, which extends about one-fifth of the extenders, would cut taxes by more than $800 billion over ten years. Extending the rest of the expired tax provisions would cost another $200 billion. If taxes are cut by $1 trillion, future efforts to control the debt would become significantly more difficult.

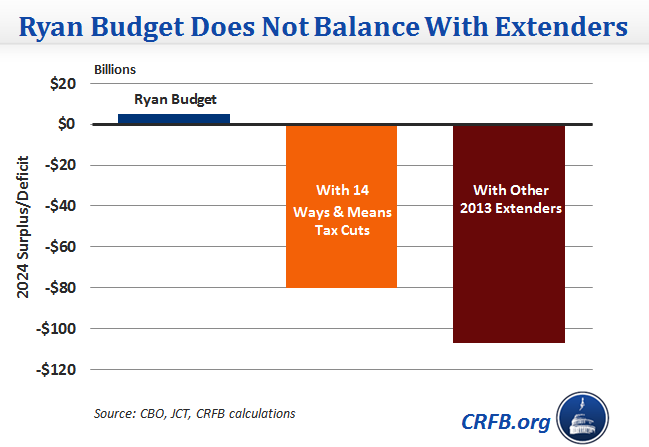

Chairman Ryan's budget, this year, was able to achieve a balanced budget within 10 years using $5.1 trillion of spending cuts, but that budget relied on current revenue levels, rather than the $800 billion of tax cuts subsequently passed by the Ways & Means Committee. If these costly policies passed in the lame duck, the Ryan budget would need even more savings to get to the same point.

The 14 provisions would add $85 billion to the debt in 2024 alone, the year that Ryan's budget had a $5 billion surplus. Extending the other provisions not yet considered by the Committee would add another $25 billion. Either way, it would put the Ryan budget in deficit in 2024.

If all these provisions were extended permanently, a future "revenue-neutral tax reform" would raise $1 trillion less than before. Given that solving our debt problem will eventually require more revenue, not less, policymakers should avoid increasing the debt through these baseline games.

Still a Chance for Agreement on Corporate Tax Reform?

Last week, a column by former National Economic Council director Gene Sperling argued that despite apparent partisan differences, "Corporate Tax Reform Is Doable in 2015." He identified five sources of agreement between the business tax reform framework of President Obama and the detailed draft published by House Ways & Means Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI). The two plans have similar tax rates on business, include a minimum tax on foreign earnings, boost infrastructure spending, and devote tax incentives to small business. And notably, both plans used the same current law baseline and were revenue-neutral compared to it.

As Sperling explains, the tax extenders are key to any discussion of revenue neutrality.

Currently, Congress tends to pass short-term extensions of a large assortment of “tax extenders” each year without paying for their 10-year, $450 billion cost.

Under Mr. Camp’s plan, revenue neutrality requires that Congress pay for extenders it wants to continue. If we define revenue neutrality in this way, Republicans can claim they aren’t raising long-term taxes, while progressives and deficit hawks can claim the plan would raise $450 billion compared with current practice. For this to work it is critical that tax reform not use gimmicks to shift costs outside the budget window.

Sperling uses a smaller $450 billion figure (rather than $700 billion) for the tax extenders because he is not including the costly bonus depreciation. That provision was originally enacted as temporary stimulus and is not considered a traditional tax extender, but plans in the House and Senate would extend it.

We've called on Congress to pay for the tax extenders so they don't make the deficit worse. This responsible approach was taken by both Chairman Camp and President Obama. Camp's tax reform proposal, the House budget resolution, and the President's business tax reform framework were all revenue-neutral compared to current law (without extenders). President Obama's budget included some of the extenders but proposed more than enough revenue offsets to pay for them. In fact, Sperling explained that some of the reason the President hasn't called for rates quite as low as the Republicans is to pay for a permanent and expanded Research & Experimentation Tax Credit.

We welcome efforts to reform the overly complicated tax code, but lawmakers should not use tax reform as an excuse to cut taxes and increase the debt.

Related Posts: