Tax Extenders: PAYGO or No Go

The year is rapidly coming to a close, with only 11 days left that the House plans to be in session. Before the year's end, Congress is supposed to hear from the budget conference committee on the results of their negotiations, but lawmakers also have a few other year-end events to handle.

Among them is consideration of the tax extenders, dozens of temporary provisions that expire annually. Extending these tax breaks has become something of an annual holiday tradition for Congress. Although these costs may be traditional in the recent past, policymakers should not assume that they are automatic. Any budget deal should not count "savings" from letting a provision expire as scheduled, and any extended tax provision should be treated with a "pay as you go" principle — lawmakers either need to find savings elsewhere to offset the cost of an extension, or let the provision expire.

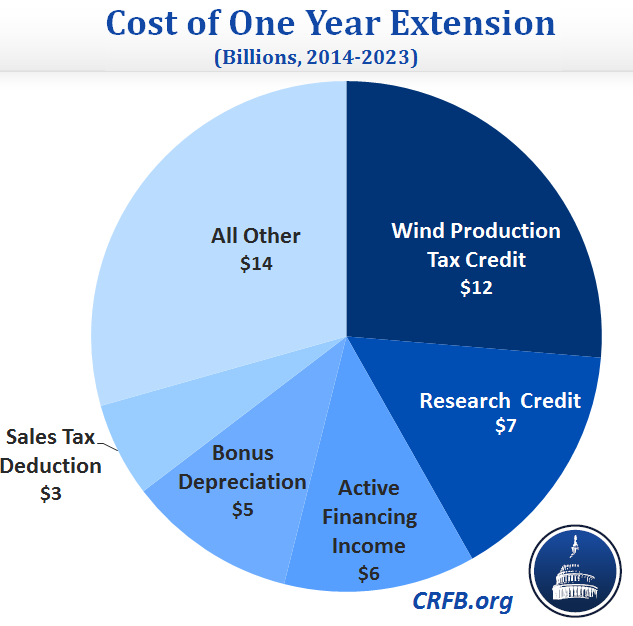

The Joint Committee on Taxation lists 64 provisions in the tax code that will expire at the end of the year. Although estimates for most of the provisions are one year old, the normal extenders would increase the ten-year deficit by approximately $40 billion if they were extended for one more year. The vast majority of the money, about 85 percent, is for business or energy provisions. One additional extender, bonus depreciation, represents a timing shift that would cost $5 billion overall, $50 billion in upfront costs over the next two years that are mostly offset in the following eight.

Not all of these extenders are equally sized. Most of them cost under a billion dollars; approximately 50 small provisions make up 30 percent of the total cost. The larger extenders are the wind production tax credit, which gives wind farms a per-cent credit for every kilowatt-hour of electricity they produce, the credit for research and experimentation expenses, an "active financing exception" that allows U.S. financial institutions to defer taxes on some of their overseas income, and the deduction for state sales taxes paid.

Source: CRFB calculations from the score of the American Taxpayer Relief Act, Congressional Budget Office.

Recent reports suggest that some lawmakers are considering letting some of these provisions expire and counting the savings as new revenue, which could then be paired with targeted spending reductions to reach a budget deal. There's a big problem with this plan: lawmakers would set an artificially low bar. They would be assuming that all temporary tax breaks are extended forever and then give themselves credit for letting a provision expire on schedule. That's certainly not how the budget scorekeepers would treat a bill, nor should they. Both JCT and CBO treat current law as the norm: extending a tax break costs money, and letting it expire on schedule has no effect. Following this agreed-upon budget convention is the most responsible thing to do. If lawmakers want to extend a provision beyond its current expiration, they should acknowledge the additional costs and offset them.

And lawmakers would be wrong to assume that every tax break is routinely extended. Many are, but the fiscal cliff legislation at the end of 2012, for example, let almost a third of the provisions (21 of 76) that expired in 2011 and 2012 lapse. Some of the ones that were extended, such as special breaks for film and television production or special depreciation schedules for racetracks and race horses, attract negative media attention every year. Furthermore, Senate taxwriters Max Baucus (D-MT) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT) have said that the Finance Committee will not issue a separate bill for tax extenders, choosing to address the provisions within tax reform. But as noted by the Congressional Research Service, "With tax reform efforts unlikely to be completed in 2013, it seems likely that the tax provisions scheduled to expire at the end of 2013 will lapse, at least temporarily." Even if the provisions lapse, lawmakers have sometimes passed them retroactively; for example, most of the provisions that expired at the end of 2011 were not extended until the end of 2012.

Hopefully, tax reform will end the uncertainty surrounding many tax extenders, either extending them permanently or letting them expire. But if lawmakers are interested in preserving the provisions before 2014, they could be considered in the normal process. If lawmakers paid for extending some of these provisions with new revenue, they would have a bill that scores as revenue-neutral, but actually enhances the long-term deficit picture by exchanging a temporary short-term cost for permanent long-term deficit reduction. Further, dealing with extenders now provides an opportunity to consider each provision instead of waiting until the end of next year, when the sense of urgency would pressure lawmakers to extend them en masse in a deficit-financed year-end package.

With tax reform unlikely to tackle extenders by the end of the year, lawmakers will need to tackle them in a separate bill in order to keep them from expiring. If they choose to extend the provisions, they should abide by PAYGO, paying for the additional costs of an extension.