Ending Taxes Below $150,000 Would Lose $10 to $15 Trillion

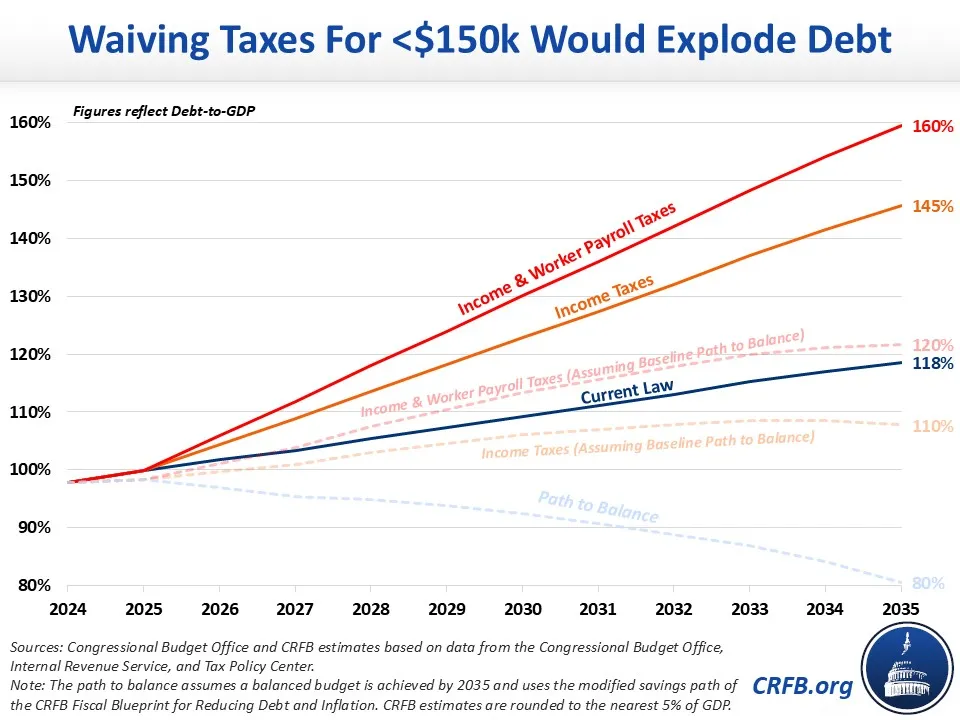

Members of the Trump Administration and Congress have recently discussed the idea of waiving all taxes for those making less than $150,000 per year, possibly after the budget is brought into balance. Even if enacted in a targeted manner, we estimate such a change would reduce revenue by roughly $10 trillion through 2035 if applied to income taxes only and $15 trillion if applied to employee-side payroll taxes as well. This would boost debt to between 145 and 160 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2035, up from 118 percent under current law.

Currently, about a quarter of all gross income taxes are paid by individuals or households with adjusted gross income of less than $150,000. Under this estimate, we assume that if income taxes were eliminated for those making up to $150,000, taxes phased back in gradually up to $200,000 of income, and the rest of the tax code were to remain unchanged then revenue would fall by roughly $10 trillion – or 2.7 percent of GDP – over a decade. Were those making below $150,000 also refunded for the worker (but not employer) share of their payroll tax contribution, revenue loss would total roughly $15 trillion, or about 4 percent of GDP.

Revenue Loss from Waiving Taxes on Income <$150,000 per year

| Dollars (2026-2035) | Percent of GDP (2026-2035) | |

|---|---|---|

| Income Tax | $10 trillion | 2.7 percent |

| Income and Worker Payroll Tax | $15 trillion | 4.0 percent |

Sources: CRFB estimates based on data from the Congressional Budget Office, Internal Revenue Service, and Tax Policy Center.

Notes: Numbers are rough and rounded. Only the employee side of the payroll tax is waived.

If enacted relative to current law, ending taxes on income below $150,000 would boost debt by $12 to $18 trillion with interest, increasing debt-to-GDP to between 145 and 160 percent – compared to 118 percent under current law. If enacted after achieving a projected balanced budget, the policy would increase projected debt from about 80 percent of GDP to between about 110 and 120 percent of GDP by 2035.

The revenue loss from this proposal could differ – and could be much larger – under different design assumptions. We model this proposal as a $150,000 itemized tax deduction that quickly phases out from $150,000 to $200,000 in income. Because it is an itemized deduction, taxpayers have the option to take this or the standard deduction, and all other elements of the tax system remain as they are under current law. Under this design, the deduction would be identical for all taxpayers regardless of filing status and would not affect the receipt of credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which can cause some taxpayers to have a negative tax liability. We assume an additional payroll tax exemption may take the form of a refundable income tax credit against the taxes.

If the proposal were to instead take the form of increasing the standard deduction to $150,000, the revenue loss would be much higher as nearly all taxpayers would shift to the standard deduction and enjoy a tax cut as a result.

Behavioral and economic changes could also change the score. With such a large exemption and rapid phase out, taxpayers would likely change their behavior and income reporting and realization to take advantage of the exemption. The change would encourage more economic activity by reducing tax rates for those making below $150,000 per year, but it would discourage economic activity by creating very high effective marginal tax rates between $150,000 and $200,000 and by adding substantially to the national debt.

Importantly, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick has said the proposal would be contingent on achieving budget balance first. Achieving an immediate balanced budget and maintaining it would require at least $22 trillion of savings over a decade, while achieving balance by 2035 might require around $17 trillion. Accounting for interest costs, ending taxes on households below $150,000 would thus reverse roughly two-thirds to more than all of the deficit reduction from a path to balance.

Given the already unsustainable fiscal situation, policymakers would be wise to improve our debt trajectory before thinking about adopting new proposals that would massively increase deficits.