Should Congress Extend Bonus Depreciation?

The Ways and Means Committee voted on a number of tax bills last week, including legislation that would restore and expand bonus depreciation at a cost of $360 billion over the next decade (including interest). Although there are reasonable arguments for and against this measure, permanent changes to depreciation schedules should be dealt with in the context of comprehensive tax reform and fully offset so as not to add to long-term deficits.

For background, bonus depreciation is a recently expired tax provision that allowed businesses to write-off half the cost of new capital investments immediately, instead of deducting them over time as normal depreciation rules dictate. Bonus depreciation was originally passed and extended as a temporary stimulus measure in 2008 designed to encourage business investment while the economy was weak. Making this provision permanent as a form of stimulus would make little sense, since, as the Congressional Research Service has noted, "its temporary nature is critical to its effectiveness." Additionally, the Tax Policy Center has argued that many businesses with too little income or are losing money don't benefit from bonus depreciation, especially in times of economic recovery, and that it may not have much of an impact on long-term investment.

The argument for permanent bonus depreciation – which is supported by the Heritage Foundation, the Tax Foundation, Americans for Tax Reform, and others – is that it would move the tax code toward "full expensing," or allowing all capital purchases to be deducted immediately, moving the tax code closer to functioning like a consumption tax. By allowing every capital purchase to be made with tax-free dollars, expensing would create incentives for companies to invest in new equipment and structures. In turn, more investment should lead to higher economic output.

But failing to offset such changes would lead to higher deficits, which would represent a drag on investment and the economy. Furthermore, retaining bonus and accelerated depreciation would make it nearly impossible to reduce the corporate tax rate below 30 percent on a revenue-neutral basis without going beyond corporate tax expenditure reductions. Thus, tax rates would need to be higher than they would otherwise be in order to keep bonus depreciation. Proponents of full expensing also suggest that bonus depreciation is a tax cut that pays for itself, citing dynamic revenue estimates that show increased economic activity will bring in more revenue than the provision costs. These dynamic estimates are highly uncertain and change dramatically using different assumptions.

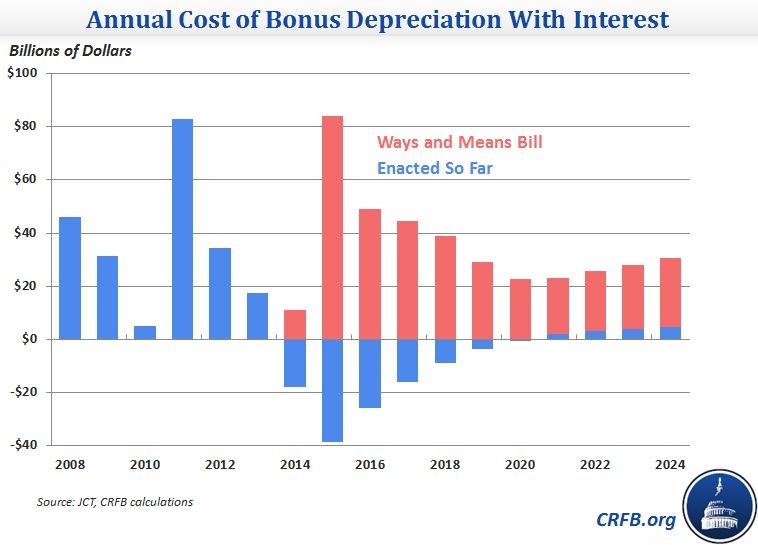

To date, bonus depreciation has added $220 billion to the deficit. If bonus depreciation remains expired (as under current law), half of those costs will be recovered. If the Ways and Means provision extending it permanently is signed into law, the total costs of bonus depreciation will rise to $507 billion (including interest costs). The Ways and Means proposal itself will add $360 billion to the deficit over the next decade, including $245 billion from restoring bonus depreciation, $40 billion from expanding it, and $85 billion in interest costs.

Although policymakers could offset this cost in isolation, it would make more sense to consider it in the context of comprehensive tax reform. Bonus depreciation interacts with many other parts of the tax code, especially those related to cost recovery. Indeed, Chairman Camp, former Chairman Baucus, and the Wyden-Gregg tax reform plan all moved in the opposite direction, reducing accelerated depreciation to pay for lower tax rates. While some might argue that expensing is more economically beneficial than lower rates, making this decision on an ad-hoc basis can lead to unnecessary complications and ultimately make tax reform more difficult.

Moreover, there is an interaction between expensing and the deductibility of interest that needs to be considered. If bonus depreciation were restored with no other changes to the tax code, companies would be able to purchase equipment with borrowed money, deducting half the equipment cost immediately and the interest on the loan over time. According to the Congressional Research Service, this would lead to a negative 37 percent tax rate on loan-financed equipment. Such a incentive to borrow may be undesirable, which is why the 2005 Tax Reform Panel recommended accompanying full expensing with the elimination of the interest deduction (Howard Gleckman of the Tax Policy Center recently explained this point in more detail).

Ultimately, policymakers can consider making full or partial expensing a part of the tax code. But if they do, they should do so in the context of comprehensive reform that addresses all potential interactions, weighs the costs and benefits, and follows the example in Chairman Camp's Tax Reform Act of 2014 to responsibly pay for any new or extended provisions. It would be fiscally irresponsible to extend bonus depreciation, or any of the traditional tax extenders, without offsetting savings.