Reset the Fiscal Debate, But Towards a Comprehensive Fiscal Plan

In a new paper, the Center for American Progress's Michael Linden makes the case for resetting the fiscal debate. His main point is that given improving deficit projections, the recent experience of developed countries, and developments in academic research, it is wise to shift the focus away from a large deficit reduction agreement. While the long-term deficit is not solved, he says, the urgency with which lawmakers have pursued deficit reduction has been counterproductive and needs to be done away with. Instead, he proposes repealing three years of the sequester and partially offsetting the costs. As he says:

No more pretending that the sky is falling. No more rash actions to cut the deficit without regard for real-world impacts. No more calls for an ever-elusive grand bargain. No more super special committees or draconian automatic punishments intended to force action. Improving our national finances is still an important goal—that has not changed. But so much else has, and the debate must change too.

Linden has three main arguments. The first is that improvements in CBO's deficit projections have bought the federal government more time in dealing with the debt. Linden's second main argument is that the case for deficit reduction has been weakened by the Reinhart and Rogoff controversy as well as the experience of austerity in Europe. Finally, Linden argues that the drive to enact deficit reduction has led to some poor policy outcomes like sequestration. We will evaluate these three arguments in turn.

CBO's Projections Have Bought Us More Time

CBO's projections have greatly improved since 2010, a welcomed sign, but as we've shown before on The Bottom Line, our debt problems remain far from solved, and the progress we've made should not be used as an excuse to put the issue on the back burner. Linden notes that a great deal of deficit reduction has happened already, especially through cuts to discretionary spending. We've previously estimated that lawmakers have enacted $2.7 trillion over ten years since the beginning of FY 2011, when our debt problems entered center stage. Linden finds a similar figure.

We noted this as well in our recent analysis of the progress made by policymakers. The savings we've enacted so far really represent the lowest-hanging fruit in the budget while the truly tough and more sweeping reforms to entitlement programs and the tax code have not been made yet. Going forward, the growth of health care spending and the failure of revenue to keep up will drive deficits and debt higher.

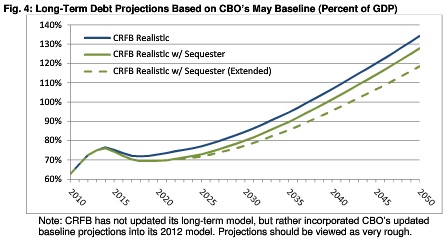

Source: CRFB

Our Realistic Baseline projects that debt will fall from a high of 77 percent to 72 percent by 2019, but it will then quickly rise to 76 percent by 2023 and to over 130 percent of GDP by 2050. We have estimated that it would take an additional $2.2 trillion over ten years to put debt on a clear downward path ($1.6 trillion if the sequester remained in effect). We need to address entitlements and revenue to make our long-term debt picture sustainable, but unlike cuts to appropriations, these reforms will take more time and will need to be phased-in to allow people time to adjust to the changes.

Source: CRFB

Linden also notes that health care projections have fallen as CBO incorporates a recent slowdown of health care cost growth. While an encouraging sign, it is best to exercise caution, as much of this slowdown is likely temporary and related to the recession. Many studies have found cyclical factors to be the main reason for the slowdown, so it is best to be conservative and take advantage of health care savings policies that have been proven to reduce both public and overall health care spending. However, even if health care costs do slow on a more permanent basis, there is still the issue of population aging, which is the predominant factor in pushing up spending in both Social Security and health care programs over the next 25 years.

The Argument for Deficit Reduction Has "Crumbled"

Linden argues that the evidence for the need for deficit reduction has been greatly weakened due to the Reinhart and Rogoff controversy and the experience of austerity. Linden focuses his attention on the 90 percent threshold, which does become less apparent after revisions to the R&R methodology. However, even after the authors corrected their errors, the paper still shows a negative relationship between debt an growth. This is consistent with other supporting literature that has shown a negative relationship between debt and growth, including studies from the Congressional Budget Office, International Monetary Fund, Bank of International Settlements, OECD, and others. The R&R controversy has weakened evidence for a specific threshold, but this certainly should not be interpreted as evidence that the link between economic growth and debt has weakened overall.

Deficit Reduction Efforts Have Led to Some Poor Policy Outcomes

The road to putting the budget on a sustainable path has been a difficult one. There is no question, and Linden points out, that the 2011 debt ceiling debacle came with considerable cost to the economy and even to the budget. And the mindless sequestration we have allowed to abruptly cut spending across the board is no way to budget.

Yet it is important to remember that these policy outcomes are at least in part the result of the failure to enact a comprehensive deficit reduction plan. The standoff that lead to the last-minute Budget Control Act deal in August of 2011 came after Speaker Boehner and President Obama were unable to agree to a larger deficit reduction package. And the Super Committee’s failure to do the same is what ultimately lead to the sequester.

Indeed, serious movement on tax and entitlement reforms may represent the best or perhaps even the only way to reverse the sequester currently in place; and may help more easily facilitate an agreement to raise the debt ceiling. As we wrote in our recent report, "What We Expect from the Upcoming Fiscal Discussions," these fiscal speed bumps are likely to be coupled with a discussion of our long-term debt burden, and it may be difficult to move forward without a debt deal:

At present, there is substantial disagreement between the House, Senate, and the Administration over how to deal with the sequestration. As a result, House and Senate appropriators are a full $91 billion apart on next year’s funding levels and will need to resolve this difference by October 1st. Meanwhile, the Treasury Department will likely run out of extraordinary measures to avoid hitting the nation’s debt ceiling sometime this fall, and the necessary step of raising the debt ceiling may prove difficult without a broader agreement to address the debt.

Turning the conversation away from fiscal sustainability will only increase the temptation put aside the budget until a last minute fix is needed, which rarely leads to good policy.

*****

Linden's paper is a reminder of the progress we have made so far but also of the costs of waiting and failing to take up politically difficult reforms. As we turn our attention to replacing the ongoing sequestration as well as dealing with the debt limit and FY 2014 appropriations this fall, it is time to hit the fiscal reset button, but not to put fiscal sustainability aside as Linden suggests. Rather, lawmakers need to turn their attention to the hard choices of entitlement and tax reform, which we will need to do if we are going to be able to put debt on a sustainable long-term path.