Most of Deficit's Decline Because Tax Breaks Aren't Included

Much of the press coverage of the updated projections issued by the Congressional Budget Office last week focused on the fact that the deficit would be $59 billion lower in FY 2015 than it was in FY 2014. But those headlines overlooked a major reason the deficit is projected to decline: Congress is waiting until after the fiscal year ends to revive a host of expired tax breaks. These tax breaks expired last year but are expected to be taken up by the end of the year, adding potentially over $150 billion to the 2016 deficit.

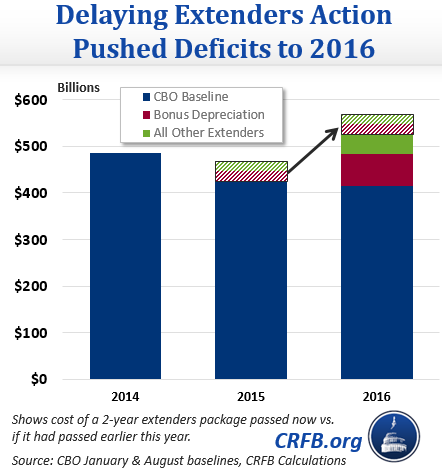

CBO's current law baseline, which assumes these "tax extenders" expire, shows deficits declining for the next two years. Given likely action on the extenders however, those projections may be unrealistic. If lawmakers continue the extenders for two years, as legislation approved by the Senate Finance Committee would do, the 2016 deficit would be about $150 billion (37%) larger than CBO's projections. Increased deficits means it's important to offset the cost for any action on extenders, unlike what lawmakers did last year.

Allowing these tax breaks to expire and retroactively extending them one or two years at a time is one way Congress masks the extenders' impact on the deficit. More than half of the deficit's drop between FY 2014 and FY 2015 is explained by the delay of Congress in extending these tax breaks beyond 2014. If the provisions had already been extended, the deficit would have only declined to $468 billion in FY 2015, instead of $426 billion. However, because the tax breaks will not show up on the government's balance sheet until FY 2016, their costs will be shifted. Ultimately, this would push the deficit in FY 2016 to $566 billion. One stimulus provision, bonus depreciation, represents 60 percent of the package's cost in the next two years.

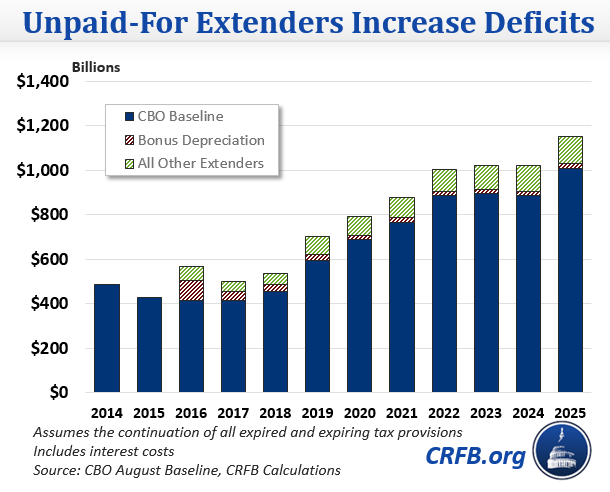

These provisions are regularly allowed to expire and are revived, but current law projections are based on their expiration. As a result, the baseline deficit appears more than $1 trillion smaller over 10 years. The Congressional budget resolution relied on a similar trick, using that revenue to make the budget balance but calling for a budget process where the costs would be added to the deficit instead. If the budget resolution assumed the extenders were permanent as its policy statement suggests, the budget would have failed to achieve balance, with a deficit of $120 billion in 2025. (See a similar analysis we did showing how the House and Senate budgets don't balance with enacted legislation.)

The same principle applies to longer projections. If the cost of extending all expired and expiring tax provisions were considered, the budget deficit would be even larger, exceeding $1 trillion in 2022, three years sooner than in CBO's normal baseline.

It's time for lawmakers to stop acting irresponsibly on the tax extenders. To prevent the 2016 deficit from rising by over one-third, they could offset the tax extenders as we proposed last year in the PREP Plan or make the package much less expensive by extending only certain provisions. Dealing responsibly with these tax provisions would prevent hundreds of billions from being added to debt over the next ten years.

Related Posts:

- Finance Committee Approves Extenders, Adds to Debt, discussing to Senate's approach of extending all provisions for 2 years

- House Considers $320 Billion of Tax Cuts, discussing the House's approach to extending only certain provisions, but permanently (and still deficit-financed)

- How to Offset the Tax Extenders (2014), describing our PREP Plan to pay for a two-year extension as a bridge to tax reform

- Tax Break-Down: Tax Extenders, explaining the history and rationale of the provisions