Setting the Record Straight on Social Security

Recently, many policymakers and commentators have called for expanding Social Security benefits rather than slowing the program’s costs, suggesting that the program’s current shortfalls are modest and easily addressed. Below, we answer some questions about Social Security to help explain why many of these calls are misguided.

Is Social Security's Financing Problem Real?

Unfortunately, suggestions that Social Security does not face a financing problem are not based in fact. Already, the costs of benefits are well in excess of revenue from payroll taxes. Social Security’s cash-flow deficit will add $75 billion to the deficit in 2014, $1.0 trillion over the next decade, and $3.8 trillion in the decade following. As we've explained, the program's past surpluses do nothing to change its very real current cash deficits. Regardless of whether past surpluses were saved in an economic sense or not, the federal government will have to borrow more to make up for the Social Security system’s cash flow deficit.

Social Security is also in trouble in its own right. The program faces a 75-year shortfall of 2.7 percent of payroll, with annual shortfalls reaching 3.9 percent in 25 years and 4.8 percent in 75 years. According to official estimates, the program’s trust fund will run out of money either in 2031 or 2033. Although these estimates are subject to some uncertainty, the CBO is 95 percent certain the trust fund will run out within a quarter century. At that point, all beneficiaries will face an immediate 23 percent across-the-board benefit cut regardless of age, income or status.

There is no question that this abrupt benefit reduction needs to be avoided, but doing so will require tough choices. As we’ve explained before, the longer we wait to act, the tougher those choices will be. The actions of those who are downplaying the magnitude of the problem and the need for action to address the shortfalls now will actually lead to deeper cuts in benefits for all beneficiaries or greater increases in payroll taxes for all workers than would otherwise be the case.

CRFB Social Security Resources

- The Reformer, a Social Security reform simulator

- Social Security and the Cost of Delay

- Analysis of the 2013 Social Security Trustees Report

Should We Expand Social Security Benefits?

In recent weeks, some have called for expanding Social Security benefits. Although there is a strong case for targeted benefit enhancements, it would be imprudent and irresponsible to enact broad-based benefit enhancements before the program’s finances are under control.

The old-age bump up provisions and minimum benefits in the Simpson-Bowles and Domenici-Rivlin plans, which would enhance benefits for low-income workers and the very old most at risk of poverty, are sensible additions to any reform plan. It is questionable whether the same is true about the across-the-board increase in initial benefits and adoption of the CPI-E proposed in legislation sponsored by Senator Tom Harkin (D-IA).

We’ve already written about the numerous flaws of CPI-E, which has been deemed an inaccurate measure of inflation by both the Congressional Budget Office and Bureau of Labor Statistics.

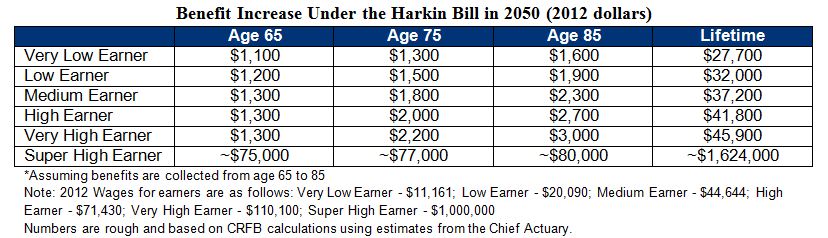

In addition to these concerns, broad-based benefit increases like those in Senator Harkin’s bill are incredibly expensive. When fully phased in, his proposal would increase costs by about 1.2 percent of payroll, resulting in a 30 percent increase in the shortfall. Rather than focusing on low-income seniors who may need support, these increases would go to everyone. For example, under his plan a 38-year old today with income in the top five percent of earners would receive a $2,200 benefit increase (in 2012 dollars) in 2050 alone.

With the Social Security program already underfunded, substantially adding to the shortfall by increasing benefits on seniors that may not need these increases would be unwise. It would be far more responsible to identify other approaches to encourage savings and improve retirement security, and to focus Social Security reforms on making that system solvent while providing targeted enhancements to those most in need.

Can Social Security's Finances Be Solved Through Higher Taxes on the Most Wealthy?

Rather than heed warnings from the Trustees and others about Social Security’s financial state, many have claimed that its shortfall could be easily closed by eliminating the $117,000 cap on wages subject to the income tax.

Yet while increasing or eliminating the cap could be part of the solution (as in Simpson-Bowles and Domenici-Rivlin), it is not sufficient to make Social Security solvent, let alone pay for benefit enhancements, and raises concerns of its own.

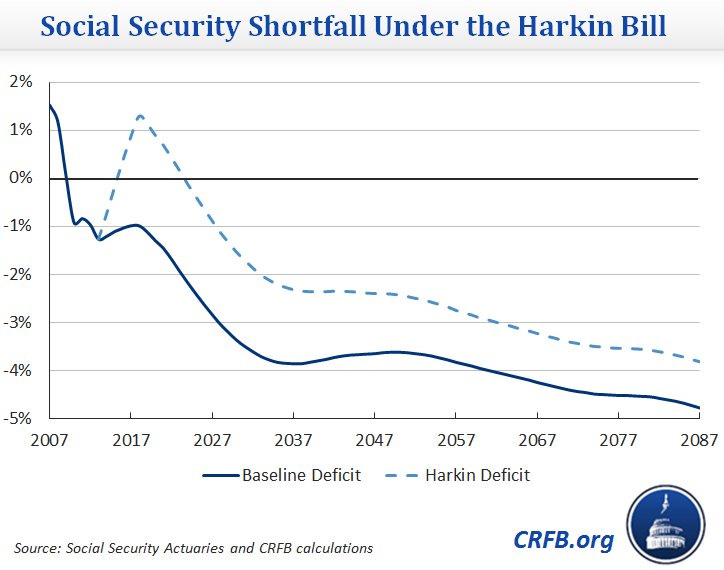

According to the Social Security Chief Actuary, repealing the taxable maximum would close about seven-tenths of the program’s 75-year shortfall, and only about one-third of the gap in the 75th year. Senator Harkin’s legislation on the whole would close only one-half of the 75-year shortfall and one-fifth of the shortfall in the 75th year. The legislation would lead to cash surpluses between 2016 and 2023, but deficits would return by 2024 and continue to grow thereafter.

Part of the reason raising the taxable maximum does so little over the long-run is that new revenue would be accompanied by higher benefits for the very wealthy. This problem could be reconciled by not crediting income above the current taxable maximum toward benefits, but that solution also raises concerns. Strong supporters of Social Security like Former Social Security Commissioner Bob Ball have argued the link between benefits and contributions is among the most important features of the program, and others like CBPP’s Bob Greenstein have argued that “breaking Social Security’s link between payroll-tax contributions and benefits… [would risk] undermining public support for the program.”

Eliminating the taxable maximum entirely would also have profound effects on the rest of the budget, especially when added to the Medicare payroll surtax and income tax rate increase that went into effect this year. In addition to the potential economic consequences of a 12.4 percent rate hike, a tax increase that large would make it politically challenging to raise more revenue from the wealthy, if it all. The government has many important needs, from financing growing health care costs to investing in infrastructure and education to keeping debt levels under control. Raising that much revenue to fund Social Security (including higher benefits for wealthy seniors) would suggest that spending more money on retirement benefits for seniors is a higher priority than other options including new investments or spending on children.

*****

There is no question that the United States could benefit from improvements to its retirement system, including regulatory, tax, and spending changes across multiple programs.

But one of the major threats to retirement security is the looming insolvency of the Social Security program. The program’s finances must be fixed in order to fully fund benefits and give workers the ability to plan and prepare. Such a fix could increase revenue coming into the system, slow the growth of benefits being paid out, and even offer some targeted benefit enhancements to those who truly need them. (Try to improve the program by using our Social Security Reformer).

But "retirement security" cannot be used to offer everything to everyone at little to no cost. That type of thinking will lead to stalemate; and as we've explained before, the longer we wait to reform Social Security the bigger the problem becomes and the harder it is to fix it. Eventually, the “do nothing plan” would result in a 23 percent across-the-board benefit cut. That's a threat to retirement security that we ought to avoid.