CBO Takes a Look at the CPI-E

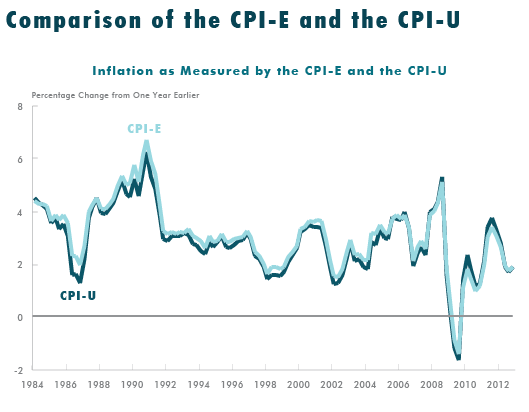

Opponents of the chained CPI often propose an alternative index for cost-of-living adjustments, the experimental CPI for Americans 62 years of age and older (CPI-E), which BLS has developed as a possible measure of inflation for the elderly subgroup. On Friday, CBO examined the CPI-E in a blog post, showing the goals of developing the CPI-E as well as some of the flaws of the measure.

The growth of health care costs has historically outpaced the rate of inflation, though there has been some slowdown in recent years. Seniors spend a much greater proportion of their income on health care, and the CPI-E weights it more heavily, accounting for about half of the 0.2 percent by which the CPI-E has outpaced the CPI-U since its development.

Source: CBO

Much of the other half of the difference between CPI-E and CPI-U is due to the larger weighting of housing in the CPI-E. The CPI incorporates an "imputed rent" based on the value of housing. However, given as many seniors have paid off their mortgages, the price of housing may play a smaller role in seniors' cost of living than the measure indicates.

CBO further describes some of the issues with the CPI-E:

It is unclear, however, whether the cost of living actually grows at a faster rate for the elderly than for younger people, despite the fact that changes in health care prices play a disproportionate role in their cost of living. Determining the impact of rising health care prices on the cost of someone’s standard of living is problematic because it is difficult to measure the prices that individuals actually pay and to accurately account for changes in the quality of health care...Many analysts think that BLS underestimates the rate of improvement in the quality of health care, and some research suggests that such improvement may make the true increase in the price of health care more than 1 percentage point a year smaller, on average, than the increase in that price measured in the CPI. If that is the case, then all versions of the CPI overstate growth in the cost of living, with the overstatement being especially large for the CPI-E because of the large weight on health care in that index.

Switching to the CPI-E by itself would not address two of the problems of the traditional CPI: subsititution bias and small-sample bias. We've covered substitution bias before on The Bottom Line. If the relative prices of two substitutable goods -- say, apples and oranges -- change, consumers are expected to change their buying habits accordingly. The traditional CPI is only able to adjust when the market basket of goods in the CPI is revised, but the chained CPI takes this substitution bias into account and therefore more accurately measures inflation.

The other major flaw of the traditional CPI, small-sample bias, is often ignored but is also relevant. CBO's recent post examining differences between the traditional index and chained index offers a detailed explanation of how the small sample of items used in the calculation of indexes in specific metropolitan areas can upwardly bias the CPI.

BLS creates the item-area indexes using, on average, prices of only about 10 examples of an item. Such a small sample creates a measurable upward bias in those indexes. Because the traditional CPI is calculated as an arithmetic average of those indexes (and the arithmetic average is unbiased), any bias contained in the item-area indexes carries through to the overall CPI.

...The chained CPI-U is also largely free of small-sample bias because of the way in which it is computed. Both the traditional CPI and the chained CPI-U are based on the same item-area indexes, which are calculated using a geometric average. To combine those indexes into an overall estimate of price growth in the United States, however, BLS uses a geometric-average formula for the chained CPI-U, as opposed to an arithmetic average formula for the traditional CPI. The use of a geometric-average formula to combine the item-area indexes effectively makes the number of elements in the geometric average much larger, which essentially eliminates small-sample bias.

Measuring inflation is a difficult task, but the chained CPI is currently the best index available. The CPI-E was designed to measure inflation specifically for seniors, but it still suffers from some technical flaws, and there is still an open question of whether it makes sense to use this index for Social Security, which contain subgroups other than seniors. A better way to deal with any change in benefits is by providing additional protections along with the change, as was done in the President's budget and the recently released "Bipartisan Path Forward." Benefits can be adjusted and protections can be added, and both are better than continuing to use an inaccurate measure of inflation.