The Real Story on Social Security Deficits

Social Security faces a serious financial shortfall, but there is no shortage of Social Security myths designed to draw attention away from the need for action. One such myth is that because interest payments this year will cover the gap between Social Security benefit outlays and tax revenue, there is little need to worry about the financial state of the program. This claim couldn't be further from the truth.

Background

Since 2010, Social Security has been running cash deficits -- meaning that the total tax revenue it brings in from the payroll tax and income taxation of benefits has fallen short of benefit payments. So far, those deficits have totaled nearly $450 billion and this year alone will exceed $70 billion,. In their latest report "the Trustees project annual deficits for every year of the projection period."

However, the Social Security trust fund (technically, the hypothetical combined Old-Age Survivors and Disability Insurance trust fund) currently holds $2.8 trillion of government bonds which accumulate interest each year (these interest payments represents a cost to the rest of government, as we discuss later). Including this year's interest payment, Social Security is likely to run a small surplus this year -- about $15 billion -- as compared to its $70 billion cash deficit. This has led some to conclude that Social Security is in a strong fiscal position. This conclusion is wrong for several reasons:

1. Cash Deficits Are a More Meaningful Measure of Social Security's Health

In their annual report, the Trustees focus primarily on three financial measures to explain the actuarial status of the trust fund: annual cash-flow measures, long-term summary measures such as 75-year actuarial balance, and projected trust fund ratios. When the Trustees measure Social Security's annual balances, they focus on a the cash measure that excludes interest payments -- and in fact, the single-year tables they produce include no measure of balances with interest incorporated.

The focus on cash balance reflects a wise decision to illustrate the structural gap between funds consistently coming in and going out of the trust fund, rather than the transient income resulting from a large but rapidly depleting trust fund. Social Security is funded largely on a pay-as-you-go basis, meaning current benefits are paid for primarily from current revenue. As such, the structural gap between actual spending and revenue will ultimately have to be reduced substantially, if not closed entirely, to ensure the program's long-term sustainability.

None of this is to say that interest income is meaningless for trust fund solvency or should be ignored, but it tells little about the structural imbalances facing the Social Security program.

2. Social Security's Finances Are Worsening Under Either Measure

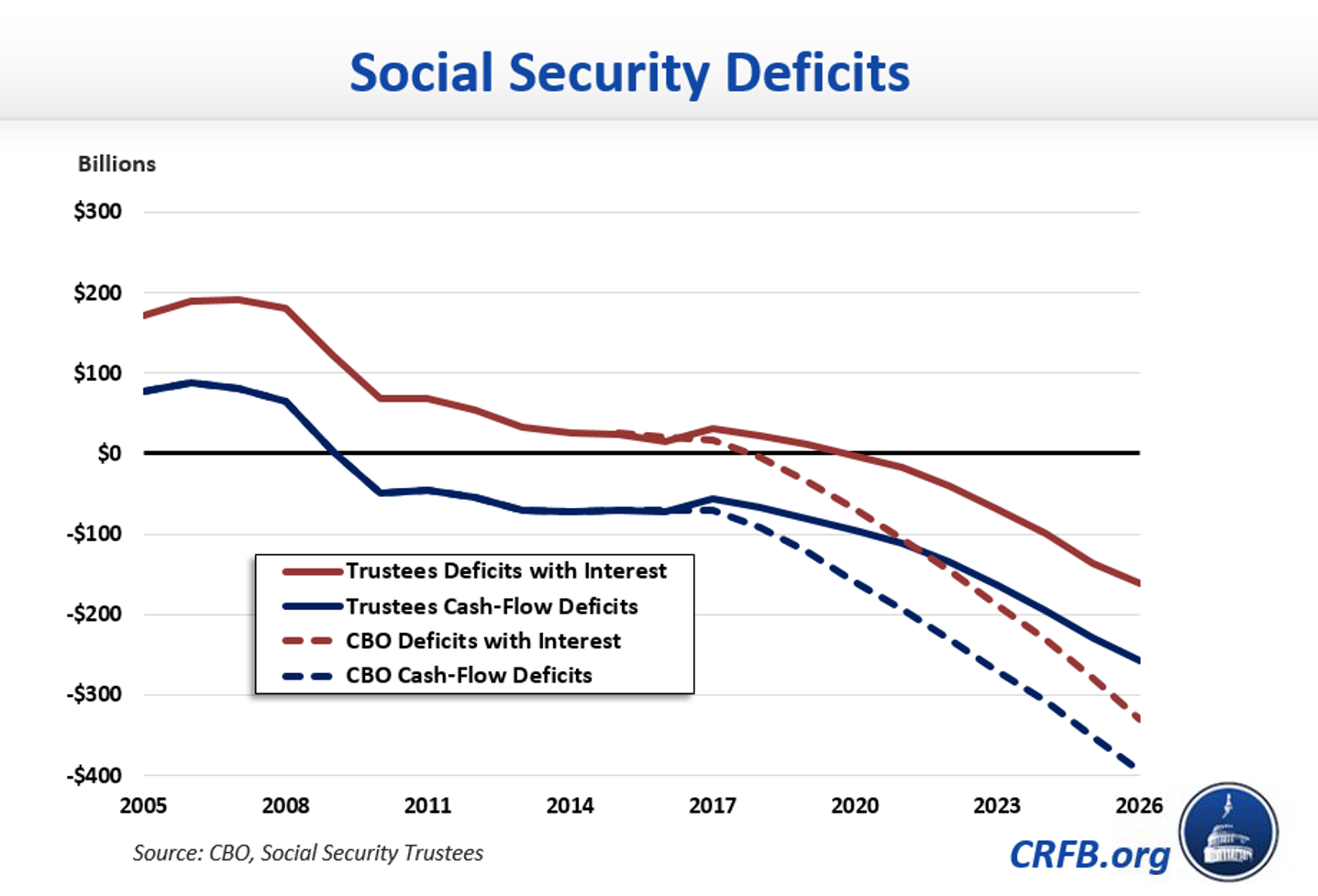

In 2007, Social Security ran a cash surplus of $80 billion and a surplus with interest of $180 billion. Just a decade later, the cash surplus is $150 billion lower (a $70 billion deficit), while the surplus with interest has fallen by an ever larger $165 billion (to about $15 billion). While it is true that some surpluses have remained under the interest-inclusive measure, the trend line is clear under either measure: Social Security's finances are deteriorating.

According to the Trustees, Social Security will begin running deficits including interest in 2020; according to CBO this will occur by FY2018. By 2026, the program will be running an interest-inclusive deficit of $160 to $230 billion and a cash-flow deficit of $250 to $400 billion. These are not signs of a financially healthy program.

3. Social Security's Trust Fund Ratio has Been Declining Since 2010

Interest income has allowed Social Security's combined trust fund to grow in nominal dollars, despite rising cash deficits since 2010. However, growth in interest income has failed to keep pace with benefit growth or inflation.

According to the Social Security Trustees, the "trust fund ratio" -- a key measure they use to compare the size of the trust fund to annual benefits -- peaked at 358 percent in 2008, and has been declining every year since 2010. By the Trustees estimates, the trust fund was large enough to pay 3.5 years worth of benefits in 2010, but can only pay 3 years worth of benefits today, will only be able to pay 2 years by 2023, and will be exhausted by 2034.

Indeed, even without accounting for the growing cost of the program (and it's growing needs), it is difficult to argue the trust fund is heathier today than it was a few years ago. In CPI-indexed dollars (an imperfect proxy for "real" inflation-adjusted dollars), the size of the trust fund peaked in 2010 at $2.85 trillion and stands at about $2.83 trillion today. The Trustees project the trust fund, in real dollars, will decline by $50 billion over the next year and $1 trillion over the next decade. In other words, under any meaningful measure the trust fund has been shrinking since 2011.

4. Interest Income Doesn't Matter When Viewing Social Security from a Budget Perspective

Although this piece generally focuses on Social Security from a "trust fund perspective," Social Security can also be viewed from a "budget perspective" that takes the federal government's unified budget into account. From that perspective, Social Security is the government's largest spending program, third fastest growing major mandatory program, and is funded with the government's second largest revenue source.

Viewed this way, interest income to the Social Security trust fund is exactly offset by interest payments made by other parts of the government to the trust fund, and this intragovernmental transfer has no real fiscal or economic impact. As the President's budget explains:

The trust fund balances are assets of the agencies responsible for administering the trust fund programs and liabilities of the Department of the Treasury. These assets and liabilities cancel each other out in the Government-wide balance sheet. When trust fund holdings are redeemed to fund the payment of benefits, the Department of the Treasury finances the expenditure in the same way as any other Federal expenditure—by using current receipts if the unified budget is in surplus or by borrowing from the public if it is in deficit. Therefore, the existence of large trust fund balances, while representing a legal claim on the Treasury, does not, by itself, determine the Government’s ability to pay benefits.

Thus, from a budget perspective, the cash flow deficits Social Security has been running since 2010 have been a draw on Treasury funds that result in additional government borrowing. The presence or absence of interest does not change that reality.

5. Social Security Faces Serious Large Long-Run Challenges

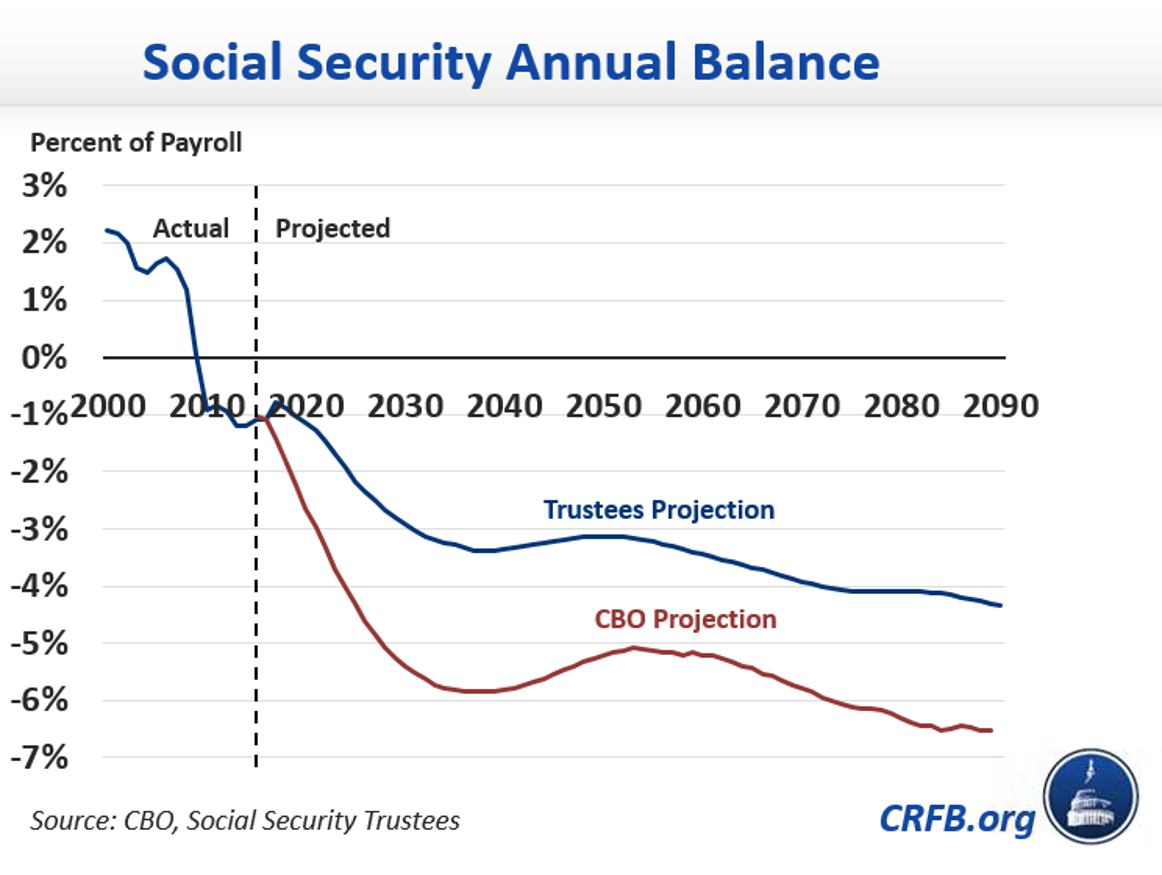

Though Social Security's large trust funds will ensure it can pay full benefits for the next decade or two despite growing deficits, the funds are far too small to cushion against the program's large and growing imbalance over the long term. This year, the program faces a cash imbalance of about 1.1 percent of taxable payroll. By 2030, the Trustees project that deficit to grow to nearly 3 percent of payroll, and by 2090, to 4.4 percent of payroll. The Congressional Budget Office is more pessimistic and projects the imbalance will grow to 5.3 percent of payroll by 2030 and 6.5 percent of payroll by 2090.

Importantly, the trust fund is projected to decline as a share of payroll every year going forward, meaning that fewer dollars of interest payments will be available to cover cash deficits. According to the Trustees, the (combined) trust fund will be depleted by 2034 and no interest payments will be available (CBO estimates insolvency in 2029).* At that point, all beneficiaries regardless of age or income will face a deep across-the-board benefit cut under current law.

Even the Trustees' more optimistic projections show insolvency is not far away. In 2034, today's 50-year olds will have just retired, and today's youngest retirees will be turning 80. Action will need to be taken soon to phase in policy changes gradually, protect current beneficiaries and low-income workers from significant changes, spread out the existing trust fund over the transition to a reformed program, ensure changes are shared among more cohorts, and give workers adequate time to plan and adjust.

Every year policymakers wait to act, the size of the problem literally becomes larger. Those spreading the myth that Social Security's finances are fine are doing a huge disservice to retirees who rely on the program as well as workers who hope to in the future.

*The Trustees estimate that there is a 95 percent chance the trust fund reserves will be depleted between 2029 and 2045.