Delaying Social Security Changes Ties Policymakers' Hands

Our analysis of the 2015 Social Security Trustees' report noted that "As time goes on, it will be more difficult to secure the Social Security programs for current and future generations with thoughtful changes instead of abrupt benefit cuts or tax increases." We previously detailed how much bigger changes need to be to keep Social Security solvent if lawmakers wait for in both the 2013 and 2014 reports. While the 2015 report showed a slight improvement in the program's projected finances, making the necessary changes slightly smaller, the problem with delaying change remains.

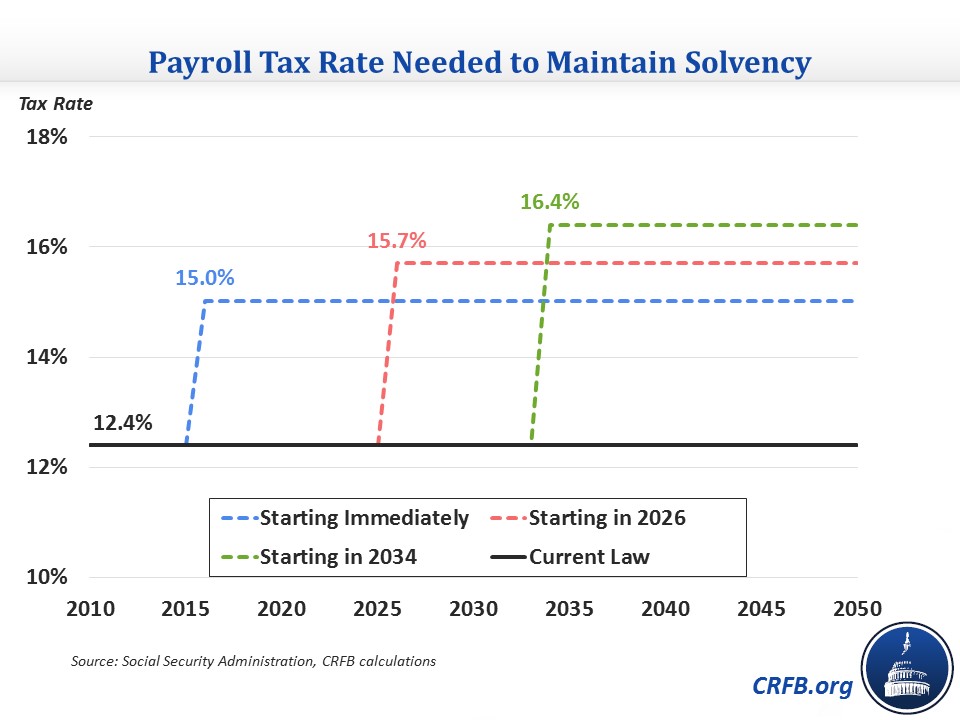

The Trustees state that it would take a 2.62 percentage point increase in the payroll tax to make the program solvent over 75 years, making the rate over 15 percent instead of the current 12.4 percent. Delaying the increase by ten years raises the necessary increase to 3.3 percentage points for a new rate of 15.7 percent. Lawmakers could also undertake gradual payroll tax rate increases, but those rates would need to be slightly higher, particularly if they waited until 2026. Finally, waiting until 2034, when the Trustees project the trust fund to become insolvent, would require a 4 percentage point tax increase for a new rate of 16.4 percent. By then, a gradual increase would not be able to keep the trust fund solvent.

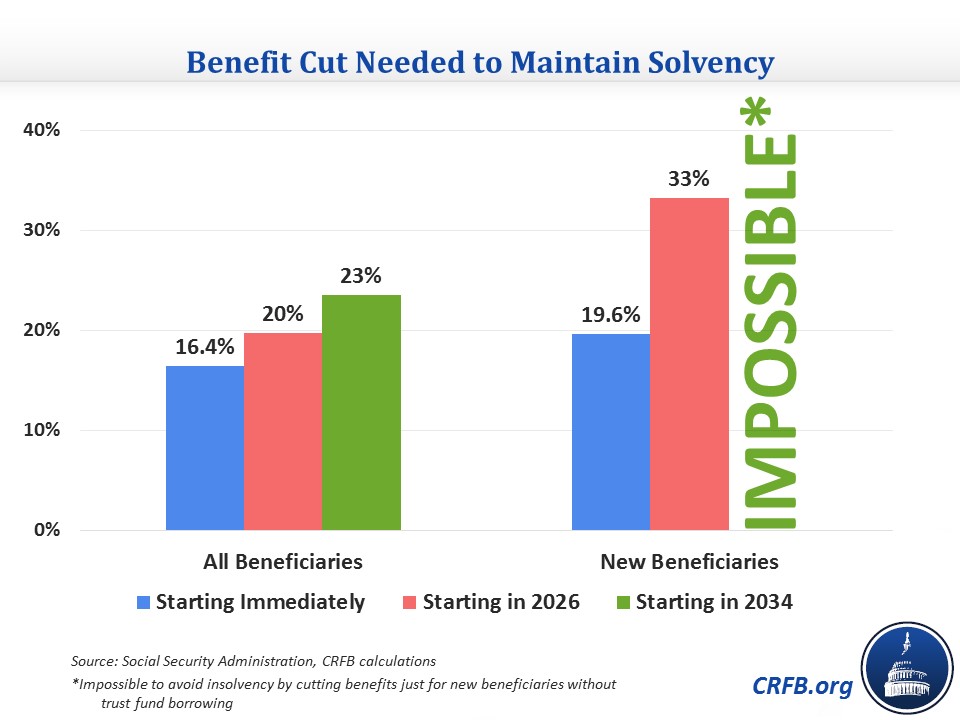

Looking at benefits, it would require a 16.4 percent cut to all benefits starting now to ensure 75-year solvency. Waiting ten years increases the necessary cut to about 20 percent, and waiting until 2034 increases the cut to about 23 percent. The result is more apparent when only looking at cutting benefits for new beneficiaries, an approach generally favored by policymakers. The required cut for all new beneficiaries starting now is 19.6 percent. That cut is relatively close to the size of the cut for all beneficiaries, but delaying change causes rapidly increasing necessary cuts. Waiting ten years increases the necessary cut to about one-third, and by 2031, even eliminating benefits for new beneficiaries would not keep the trust fund solvent. As with payroll tax increases, the benefit cuts could be made gradually, but they would need to be higher and especially so in later years and if the cuts are limited to new beneficiaries.

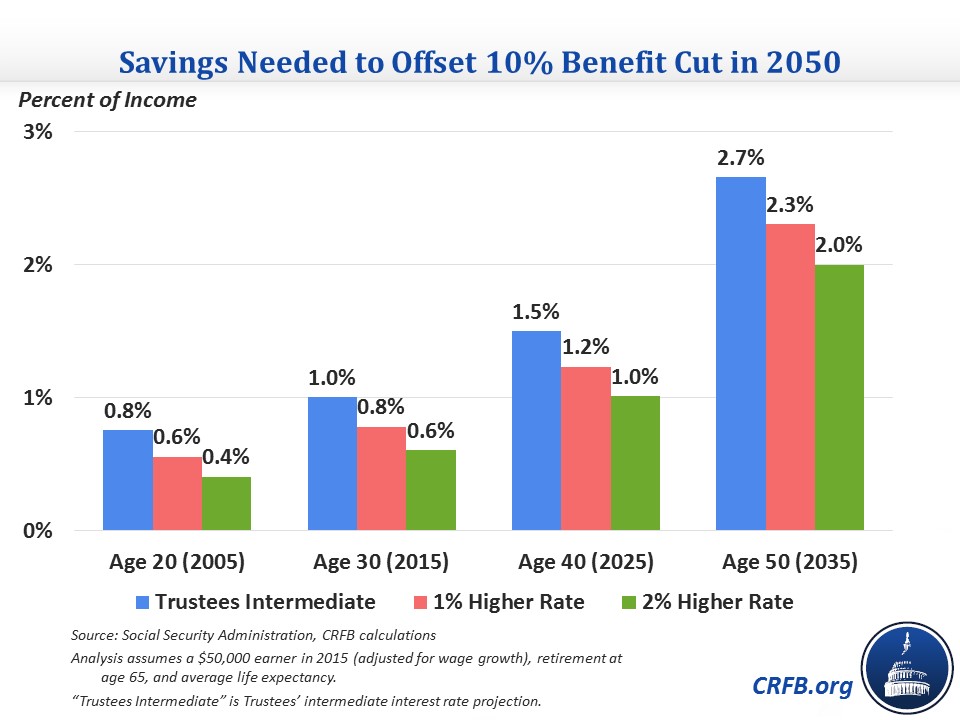

Another way to look at the harm from waiting is to look at individuals' savings responses to a cut in benefits. In order to fully compensate for an announced 10 percent benefit cut in 2050, a 30 year-old in 2015 would have to save an average of 1 percent of his or her income per year (assuming a $50,000 income in 2015 adjusted for wage growth). That amount grows over time to the point that the same person in 2035 would have to save 2.7 percent, nearly three times the amount if they knew of the cut 20 years earlier. These amounts assume a rate of return equal to the intermediate projections of the Social Security Trustees; assuming higher rates of return would make these amounts lower, but they would still rise significantly over time.

These numbers show that not only do the necessary changes get larger the longer policymakers wait, but also the options they have to work with shrink. Having gradual or delayed tax changes or having benefit changes affect only new beneficiaries becomes much more difficult the closer we get to the insolvency date. If lawmakers do not act soon, they will find themselves having to make much more disruptive changes for beneficiaries, taxpayers, or both. The Trustees agree:

The Trustees recommend that lawmakers address the projected trust fund shortfalls in a timely way in order to phase in necessary changes gradually and give workers and beneficiaries time to adjust to them. Implementing changes soon would allow more generations to share in the needed revenue increases or reductions in scheduled benefits.

To learn more about the 257-page 2015 Social Security Trustee's Report, see our 7-page paper "Analysis of the 2015 Social Security Trustees' Report." To see our 2013 report on the cost of delay for Social Security, click here.