Capital Gains and Tax Reform

Yesterday, the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee held a joint hearing on tax reform and the tax treatment of capital gains. Base broadening tax reform with the payoff of lower rates is one of the key components of both the Simpson-Bowles and Domenici-Rivlin plans. But in order to get the lower rates in a fiscally responsible way, everything must be on the table, and that includes capital gains.

CRFB's Senior Policy Director Marc Goldwein commented on this very topic in a recent article in Tax Notes. Goldwein cites that the recent Tax Policy Center piece, showing it would be impossible to achieve revenue-neutral and distributionally-neutral tax under Governor Romney's proposal, could be remedied if policymakers were willing to reduce investment incentives.

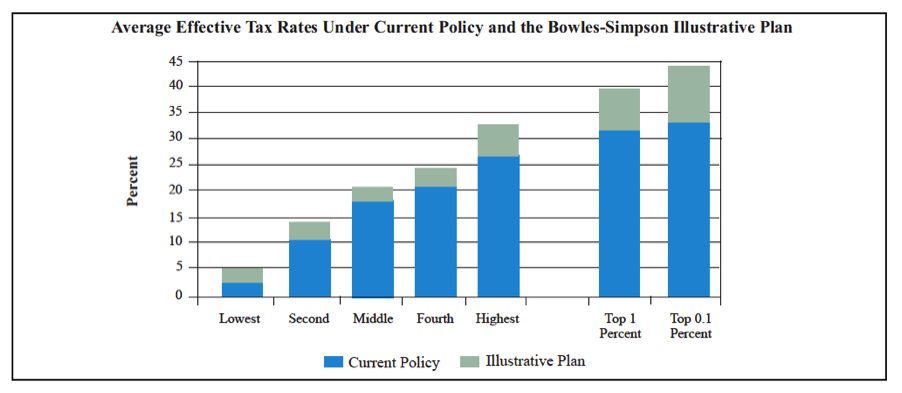

Goldwein recognizes that there is a theoretical "tax trilemma" between increasing revenue, progressivity, and growth from a simple and efficient code, but argues that the current code is so complex and inefficient that it is possible to do all three. He points specifically to the Simpson-Bowles illustrative plan, which reduces the top tax rate to 28% while raising $1 trillion of revenue and increasing progressivity.

Of course, the progressivity at the very top from the Simpson-Bowles plan comes in part from taxing capital gains and dividends as ordinary income (28%) and eliminating the "step-up basis" loophole for capital gains at death. Goldwein argues that despite popular opinion, this might not have a serious effect on growth. Goldwein points out that many studies have shown little correlation between the capital gains rate and growth. He writes:

One explanation for this weak relationship is that the benefit of lower taxes on one type of capital income may be outweighed by the economic cost arbitrage and misallocation caused by the many different rates on capital income. Under current law, short-term capital gains, long-term capital gains, interest, dividends, corporate income, small business income, wage income, retirement account income, income from bonds, and appreciation of tangible assets are all taxed differently.

Lowering overall rates and then taxing all income the same could have substantial benefits by allowing businesses and individuals to make investment decisions based on what the market, not the government, thinks is best. Taxpayers would put more of their money into wise long-term investments and hand less to tax accountants and other intermediaries. These efficiencies by themselves are likely to make up for much or all of the potential losses from higher rates on capital gains.

And, in fact, the best way to encourage savings and investment is not through lower tax rates on specific types of investment, but through a comprehensive fiscal plan that reduces "crowd-out" of investment from excessive national debt and restores confidence in the future of the economy. For this reason, tax reform that brings in new revenue is not only consistent with economic growth, but perhaps necessary for it.

This very issue was the main topic at the joint Ways and Means/Finance hearing. Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (D-MT) argued that capital gains needs to be included in the discussion, and Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) said that trade-offs between preferential rates and other priorities would need to be weighed in the context of comprehensive reform. Chairman Baucus laid out four considerations for capital gains taxation:

First, we need to consider the capital gains rate compared to the rates on wage income, dividends, and corporate income. The tax rate on capital gains is currently lower than the rate on wage income. Some say this is to avoid double taxation. But most of the time, that claim doesn't prove true. Only a third of capital gains come from sales of corporate stock. The rest have never previously been taxed before reaching individuals.

Second, we need to consider how capital gains rates affect different income brackets. Capital gains go disproportionately to high-income taxpayers. Last year, capital gains represented half the income of the top 0.1 percent of earners, but three percent for the lowest 80 percent of taxpayers. Low capital gains tax rates are the main reason why many wealthy individuals pay lower tax rates than middle class families.

Third, we need to consider our low savings rate. Americans need to save over their lifetimes. This is an opportunity for our witnesses to talk about the relationship between tax rates on capital gains and national savings.

Fourth, we must consider complexity. Experts tell us that about half the U.S. tax code – more than 20,000 pages – exists solely to deal with capital gains. That complexity, as well as the wide gap between the tax rates on income and capital gains, invites people to use all kinds of shenanigans to game the system.

Witnesses at the hearing were split on what to do with the taxation of capital gains. Len Burman of Syracuse University and William Stanfill of Montegra Capital Income Fund and TrailHead Ventures argued for taxing capital gains as ordinary income, saying that the distortions and inequities caused by the preferential rates were not worth it and that raising those rates would not impact growth or investment materially. David Brockway of the law firm Bingham McCutchen and formerly Chief of Staff at the Joint Committee on Taxation said that taxing capital gains as ordinary income may be the most efficient way to achieve a desirable distributional outcome from tax reform.

However, David Verrill of the Angel Capital Association and former National Economic Council director Larry Lindsey argued the opposite. Lindsey pointed out that when accounting for the fact that some capital gains will have already paid the corporate tax rate, the effective rate on capital gains is much higher than the headline 15 percent rate (and would go higher when accounting for the rates in effect in 2013). He also said that the much higher taxes on equity as opposed to debt were creating unhealthy distortions in terms of corporate financing. Verrill argued that increasing the capital gains tax rate would hurt small businesses and startups, especially since financing those businesses came with large risks that might not be worth it if the tax rate was higher.

Overall, there are a lot of things to consider with capital gains, both economic and political. Positive growth effects from lower capital gains tax rates must be balanced with the distortions it causes, the crowding out of investment that occurs from taking in lower revenue, and the regressivity of the preferential rates.

As Goldwein showed, it is possible to increase revenue, increase or maintain progressivity, and have a more growth-friendly tax code. The key, though, is to keep all options on the table, so different reforms can be weighed in terms of their effects on those three variables. Otherwise, lawmakers may set themselves up for too tall a task.