Assuming Costs Away Doesn’t Make SGR Deal Free

Now that we have shown that the "doc fix" proposal in the House will likely add to the debt in the longer term – refuting a key argument for not fully offsetting the ten-year cost of the bill – supporters of the legislation have come up with a cynical new argument. Specifically, supporters argue that we shouldn’t count the higher spending provided for the legislation because future Congresses are likely to enact those spending increases anyway.

Because Congress is unlikely to allow the cuts to physician payments scheduled under current law, they argue that changes to the law should not be measured against current law but against a baseline that assumes more fiscal irresponsibility – such as the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) Alternative Fiscal Scenario (AFS) – in which scheduled cuts do not occur.

Yet this argument is inconsistent with long-standing budget scoring conventions, historical precedent with respect to the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR), other descriptions of this very SGR bill, and general principles of fiscal responsibility. More to the point, the argument is circular. It assumes future Congresses will be fiscally irresponsible, then argues the current legislation is responsible because it isn’t as irresponsible as Congress would have been.

Costs should be measured relative to current law – because it’s the law

CBO budget scoring, “pay as you go” budget rules, and budget enforcement rules all measure changes in law relative to the law. This long standing budget convention is designed to give cost estimators the ability to measure the impact of a legislative change and ensure all changes are accounted for. While there is value in also understanding the impact of legislation relative to alternative scenarios (such as Congress acting irresponsibility), this information doesn’t change the facts. The law calls for a cut in physician payments, and reversing that cut costs money. It is for this reason that even the drafters of the SGR bill state that “since 2003, Congress has spent nearly $170 billion in short term patches” and that Doug Holtz-Eakin – who criticizes current law as a “pure fantasy” – himself uses a current law baseline to explain that “[r]epeal of the SGR is costly however – roughly $175 billion over the next 10 years.” (Importantly, if costs from changing current law are never recognized, lawmakers will have opened a huge loophole they could use to significantly increase the deficit.)

SGR has almost always been paid for with alternative savings

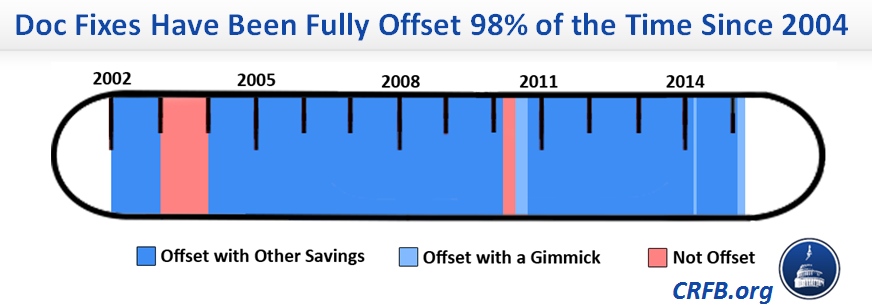

Proponents of measuring the cost of SGR reform relative to an alternative baseline point out that the physician cuts scheduled under current law are unlikely to occur. “Not in my lifetime. Not on this planet. Pure fantasy,” says Holtz-Eakin. They are right: policymakers will not allow 20 percent cuts to physician payments anytime soon. But if history is an indicator, policymakers will almost certainly pay for the cost of temporary “doc fixes” with alternative health care savings. Indeed, since 2004, 98 percent of doc fixes have been offset over the subsequent decade; and of the $170 billion in doc fix costs the drafters identify, $165 billion have been offset.1 Any fantasy that comes true 98 percent of the time is one worth believing in.

Relying on the Alternative Fiscal Scenario (AFS) has wide-reaching implications

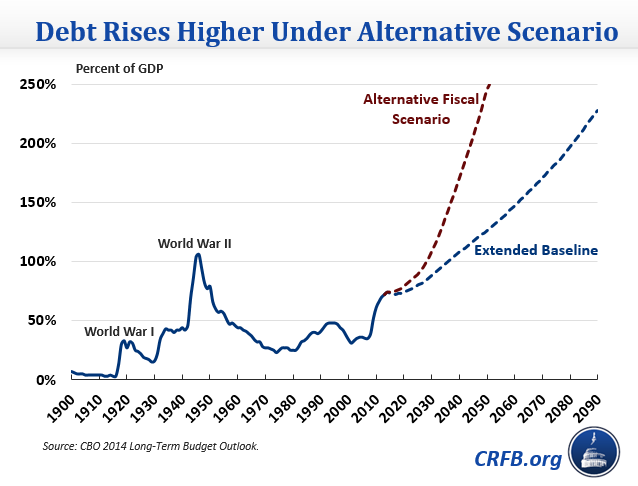

Arguments that SGR reform should be measured relative to a baseline that assumes future irresponsibility like the AFS may seem harmless, but their implications can be quite serious. The AFS assumes Congress will avoid cutting physician payments, but it also assumes that a host of temporary tax breaks known as the “tax extenders” will continue, expiring refundable tax credit expansions originally enacted in the 2009 stimulus bill will continue permanently, and “sequestration” cuts will be repealed.

Were Congress to start measuring relative to this baseline, increasing spending would be free, and there would be no need to either stick to current spending levels nor pay for sequester relief as we have twice before. Under this baseline, debt will continue to grow rapidly even in the near-term and will eclipse the size of the economy in about 15 years. In short, abiding by the AFS baseline for purposes of PAYGO rules would be a fiscal disaster.

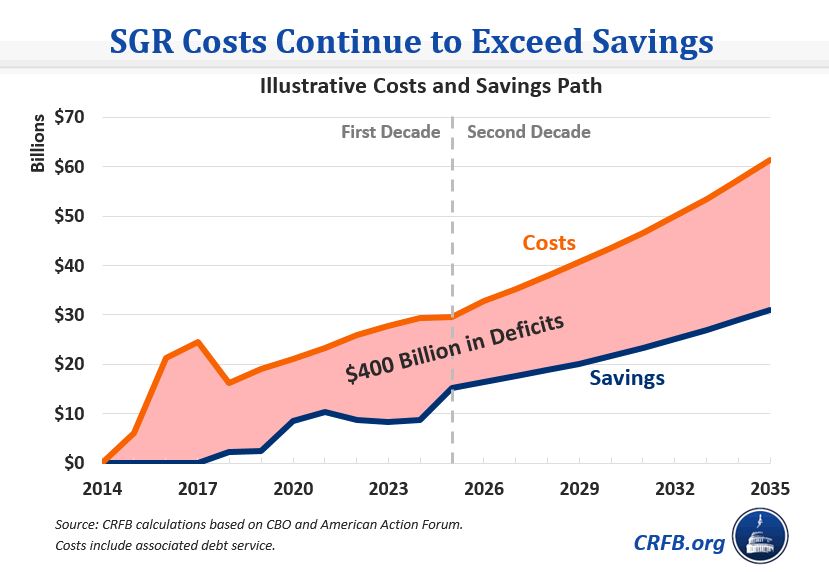

The SGR bill has significant costs – unless you assume them away

Arguing that SGR reform doesn’t cost anything by assuming the costs will happen anyway is circular logic. Not only does it give Congress a free pass for increasing already-unsustainable Medicare costs and debt levels, but it excuses actual fiscal irresponsibility today because of the prospect of hypothetical fiscal irresponsibility of future Congresses. The bottom line is that replacing a scheduled cut with a continued payment increase will cost money, and the “offsets” in the legislation will only cover a small portion of the costs. The bills own supporters admit it will cost about $140 billion this decade, and by our very rough estimates, it could add over $400 billion to the debt by the end of next decade.

No amount of hand waiving can assume away those costs.

1 We tallied the costs of all the SGR bills since 2003 and came up with $175 billion, rather than $170 billion as the drafters identify.