Reform Needed for Medicaid DSH

Federal Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments are set to face an $8 billion annual reduction – more than 50 percent – in 2025, 2026, and 2027. These payments are intended to support hospitals that care for a disproportionately high number of low-income patients on Medicaid or uninsured individuals, helping to offset uncompensated care costs.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) originally mandated the reductions, anticipating that broader health insurance coverage would lessen the need for DSH payments. However, the cuts have been repeatedly delayed.

This cycle of costly delays should end. In the short term, Congress should either allow the scheduled DSH cuts to proceed in full or phase them in while ensuring the $24 billion in projected savings through the 2025-2034 budget window is preserved.

Over the longer term, Congress should reform the DSH payment methodology to better align with hospitals’ actual needs, as originally intended. Such reforms should also include all non-DSH supplemental payments to hospitals, which – unlike DSH – have fewer or no limits, currently cost over $80 billion a year, and are growing rapidly. A unified and better-targeted approach to DSH payments would improve efficiency while significantly reducing the overall cost of federal Medicaid supplemental support payments.

In this paper, we explain:

- Medicaid DSH payments and their limits

- Required reductions in DSH spending

- The lack of a budgetary case for delaying DSH cuts

- Options for policymakers to reduce Medicaid spending and reform DSH

While states and hospitals have expressed concern about the cuts, these concerns are largely unwarranted, given the decreased role of DSH payments as a source of hospital funding. Many states consistently leave DSH funds unspent and federal support has risen due to state financing strategies and gimmicks that exploit loopholes.

Policymakers should end the repeated delays by allowing the scheduled reductions and should seize this opportunity to reform the federal DSH program comprehensively while strengthening Medicaid program integrity.

Medicaid DSH Payments and Their Limits

Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments are intended to supplement standard federal Medicaid matching funds and are directed to “deemed DSH hospitals” that serve a higher proportion of Medicaid and low-income patients compared to other hospitals in a state.1

States also have discretion to make DSH payments to other hospitals meeting minimum criteria, such as a Medicaid inpatient utilization rate of at least 1 percent.2 As with all Medicaid payments, DSH costs are shared between states and the federal government, with the federal share ranging from 50 percent up to 83 percent.

When Congress introduced the DSH payment requirement in 1987, funding was uncapped at the national, state, and hospital levels. This led to a dramatic increase in spending, from $1.4 billion in 1990 to $17.5 billion in 1992, driven by a handful of states leveraging DSH funds aggressively.3 Many states relied on financing gimmicks to maximize federal matching funds without increasing their own contributions, as we have discussed in previous briefs. In response, Congress imposed federal limits on Medicaid DSH payments in 1993, effectively curbing their growth.4

The 1993 limits included:

- Aggregate limits: Maximum amount of federal DSH matching funds that can be spent for all states across the country.

- State-specific limits: Each state is allotted a portion of the aggregate limit, known as a DSH allotment, which represents the maximum federal matching funds a state can claim for DSH payments.

- Hospital-specific limits: Each hospital’s DSH payment is capped at the amount of uncompensated care costs they incur from treating Medicaid and uninsured patients.

The aggregate DSH limit and state-specific allotments were established based on 1992 DSH spending levels rather than the actual uncompensated care costs faced by hospitals. Consequently, states that aggressively increased DSH spending through financing schemes were rewarded with larger DSH allotments, while states with more stable and modest DSH spending received smaller allocations. The disparity between the 1990s era high-DSH and low-DSH states persists today.

Required Reductions in DSH Spending Limits

In 2010, Congress passed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – legislation designed to expand health coverage to many of the then 50 million uninsured Americans by expanding Medicaid, offering income-based subsidies in new state-based exchanges, and establishing coverage mandates.

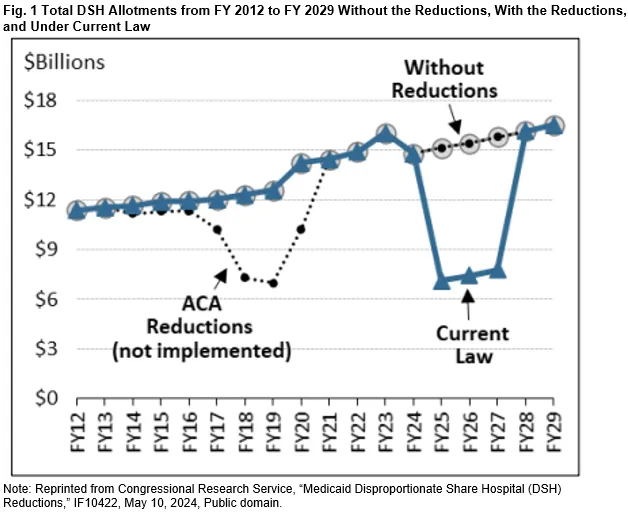

To help finance a portion of these costs, the ACA mandated an $18 billion reduction in aggregate Medicaid DSH spending based on the assumption that increased health insurance coverage would decrease the uninsured population and thereby lower hospitals’ uncompensated care costs. These DSH reductions were scheduled to phase in starting in Fiscal Year (FY) 2014, coinciding with the implementation of the ACA’s primary coverage provisions, and then ending by FY 2021, when DSH payments would revert to pre-ACA levels.5

The reductions never took place. Through over a dozen pieces of legislation, Congress altered their timing and scale. Initially, this involved pushing back the start date, reducing nearer-term cuts while gradually increasing cuts later in the budget window, to make the changes budget neutral. Other alterations delayed the cuts further without changing the scale of reductions. The current regime of cuts reflects a timeline delay plus an increase is the size of the reductions.6

DSH cuts are now set to begin on January 1, 2025, at $8 billion annually and continue through FY 2027 – totaling $24 billion.7 After FY 2027, state DSH allotments revert to their higher levels set according to DSH spending patterns from 1992. One notable impact of the many delays and alterations is that they provide opportunities for budget gimmickry by using far-off increases in cuts to pay for short-term spending increases without any intention of allowing the cuts to hit.

There is No Budgetary Case for Delaying DSH Cuts

DSH payments are poorly targeted and reflect a Medicaid financing framework that has dramatically changed over the more than three decades since DSH limits and allocations were set. From a fiscal standpoint, there is no justification for further delaying DSH cuts. Additionally, greater savings could be obtained through a comprehensive reform of DSH payments that incorporates all Medicaid supplemental payments into a unified system.

The rationale behind the ACA’s reductions of DSH payments – a decline in uncompensated care due to the ACA’s expansion of health insurance coverage – has largely materialized. The uninsurance rate is far lower today than it was prior to the ACA, falling from 17 percent in 2013 to 8 percent in 2023, with nearly 30 million fewer people uninsured despite population growth. At the same time, Medicaid enrollment has increased from 34 million in 2013 to 80 million in 2024, supported by federal payments that cover 90 percent of costs for the expansion population.

Furthermore, DSH payments have become a much smaller share of total Medicaid funding, dropping from 13 percent in FY 1993 to just 2 percent in FY 2022.8 This decline reflects both the rise in overall Medicaid enrollment and a significant increase in the expensive and rapidly growing non-DSH supplemental payments created by states once DSH payments were limited.

These newer supplemental payments totaled $80 billion in 2022 compared to just $15 billion for DSH payments.9 As we have written before, unlike DSH payments, these supplemental payments lack a statutory mandate, defined purpose, and provider-specific limits, and are distributed as lump-sum payments not tied to specific Medicaid services. They are often driven by states and providers collaborating to tax providers as a means of funding the state share of payments, shifting the state share of Medicaid costs to the federal government while inflating overall Medicaid expenditures. The rapid growth of unlimited state-directed payments tied to managed care represents the most egregious misuse of these financing strategies.

In the aggregate, these payment schemes fail to direct financial support to providers most in need and do not directly improve access for Medicaid enrollees. Instead, they allow hospitals to secure high payments from the federal government – often exceeding Medicare rates and nearing those of commercial insurance.10 This trend contributes to hospital consolidation and rising profits, particularly among large nonprofit hospitals, many of which report negligible uncompensated care costs in some states.11

Because of this growth and the changing Medicaid financing landscape, many states would not be impacted by the scheduled reduction in DSH payments and could maintain their current DSH spending levels. The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission has projected that for FY 2026, 15 states would not be impacted because their prior spending was already equal to or below the reduced DSH limits.12 Given these developments, further delays to DSH cuts are fiscally unjustifiable. Instead, policymakers should reform DSH and supplemental payments to better target resources, curb unnecessary federal spending, and prioritize patient access and provider needs.

Proposals to Reduce Medicaid Spending and Reform Medicaid DSH Payments

As the January 2025 deadline for DSH cuts approaches, Congress will likely face pressure to delay scheduled reductions once again. However, this presents an opportunity to advance meaningful DSH reform while also allowing the cuts to proceed. Ideally, reform would align the DSH program with its original legislative intent – targeting support to providers with the highest uncompensated care costs. Integrating existing non-DSH payments into a modernized, more focused DSH program could enhance the program’s effectiveness while significantly reducing federal spending. Here are possible steps of action:

Let DSH Cuts Take Effect and Make Them Permanent

Given the impetus for reducing DSH payments in the first place – paying for part of the Medicaid ACA expansion and acknowledging less uncompensated care – a fiscally responsible Congress would allow DSH cuts to proceed as scheduled and make them permanent. Since the cuts have already been accounted for in prior budgets, the resulting “savings” should be allocated to deficit reduction, preventing the use of DSH reductions as a recurring budgetary gimmick.

Alternatively, Congress could opt for a gradual phase-in of the DSH reductions over the ten-year budget window. However, the lower level of DSH spending should remain permanent once the full $24 billion in cuts are achieved, ensuring the intended fiscal savings are realized.

Reform DSH Payments to Better Reflect State and Provider-Specific Needs

If Congress opts to delay the ACA-mandated DSH reductions again, it should direct CMS to revise the DSH reduction methodology for the future in order to account for states with unspent DSH funds after any cuts took place. MACPAC has recommended that reductions should begin with those states, essentially allowing unspent DSH funds during the reduction period to be reallocated to other states, helping offset reductions and ensuring more funding is available to pay whatever hospitals have uncompensated care costs.13

More fundamentally, Congress could instruct CMS to revise how state DSH allotments are calculated to better align with each state’s actual uncompensated care costs. MACPAC has repeatedly highlighted the lack of meaningful correlation between DSH allotments and hospital uncompensated care costs under both historical spending and the ACA-spurred reduction methodologies.14 Although Congress acknowledged the need for improved DSH allocation during the reduction phase, the current system —based on outdated historical spending— still fails to effectively target and align DSH funding with actual uncompensated care.

MACPAC advocates for using a proxy measure to more precisely reflect uncompensated care needs, such as the number of individuals in a state who are likely to incur these costs.15 Such an approach could adjust for geographic variations in hospital costs and move away from the historically determined and outdated payment methodology. Policymakers could also tighten eligibility criteria for DSH payments to ensure funds are directed to hospitals serving significant Medicaid and uninsured populations. Currently, states have wide latitude in distributing DSH funds, with the only mandate being to pay deemed hospitals.

Non-deemed hospitals can qualify for DSH payments if just 1 percent of their inpatient days are for Medicaid patients, making most hospitals eligible. Raising the eligibility threshold to require a higher percentage of Medicaid inpatient days would improve the targeting of DSH funds, directing them to hospitals with larger Medicaid patient populations and greater needs.

Broaden Reform to Incorporate all Medicaid Supplemental Payments

Given that many supplemental payments were created to circumvent DSH payment limits enacted in the 1990s, it is logical to consolidate these payments into a unified system that targets funding based on need and includes clear federal, state, and provider-level limits. This reform could also tie payments to quality and value measurement and end the practice of federal support not connected to beneficiary improvements or health care goals.16 In addition to rules on the payment side, there should also be rules over state financing to reduce the ability for states to shift spending to the federal government – a practice enabled by the proliferation of supplemental payments.

A key step for reform would be to develop a new DSH allocation methodology based on uncompensated care costs (as discussed above), provided that the new formula excludes provider taxes and government hospital fund transfers from the calculation of hospital costs. Currently, when states use provider taxes to fund Medicaid payments, these taxes are counted as hospital costs for Medicaid DSH purposes, artificially increasing uncompensated care costs. Thus, excluding these inflated costs would ensure that states are not inequitably rewarded with larger DSH allotments due to financing gimmicks, creating fairer and need-based determinations of state DSH funding.

More substantially, policymakers could eliminate current authorities for supplemental payments outside of DSH, halting the creation of new supplemental payments while implementing a version of a proposal discussed in our prior brief for a Medicaid financing policy that mandates each state to contribute a minimum amount of state general funds for Medicaid payments. By requiring states to provide a minimum level of state general funds and limiting their use of provider taxes and other provider-based sources, hospitals would still receive funding to address uncompensated care costs without further increasing federal expenditures.

Under this approach, a reformed DSH system could potentially provide higher funding levels than current DSH payments. However, because the distribution would be based on actual need rather than historical spending or the availability of financing schemes, the total federal expenditure on supplemental payments would likely decrease significantly, achieving both fiscal efficiency and targeted support.

Conclusion

The current debate around Medicaid DSH payment reductions largely focuses on the immediate effects of the mandated cuts on states and hospitals. While Congress should permit these cuts to proceed as planned, a broader and more enduring challenge remains to be addressed: the need to refine the DSH program and its methodologies. This reform should include a comprehensive review of all Medicaid supplemental payments, acknowledging their rapid growth spurred by state financing gimmicks. Establishing clear limits, reducing overall spending, and strategically targeting remaining funds to those states, populations, and providers with the greatest need would ensure federal support is both efficient and equitable.

1Federal law defines “deemed DSH states” as those with a Medicaid inpatient utilization rate of at least one standard deviation above the mean for hospitals in the state that receive Medicaid payments, or a low-income utilization rate that exceeds 25 percent. 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396r-4(d).

2Hospitals also must have at least two staff obstetricians who treat Medicaid enrollees to be eligible for a DSH payment, although there are certain exceptions to this requirement for rural and children’s hospitals. 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396r-4(d).

3 Urban Institute, “The Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Payment Program: Background and Issues,” October 1997, p. 1, fig. 1, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/medicaid-disproportionate-share-hospital-payment-program.

4KFF, “Federal Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Allotments,” https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federal-dsh-allotments/ (for FYs 2010 and 2020); Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), “Chapter 3: Annual Analysis of Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Allotments to States,” March 2024, p.85, Table 3A-1, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Chapter-3-Annual-Analysis-of-Medicaid-Disproportionate-Share-Hospital-Allotments-to-States.pdf (for FY 2024).

5 Congressional Research Service (CRS), “Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Reductions,” IF10422, May 10, 2024, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/details?prodcode=IF10422.

6 Id. Medicaid DSH reductions are to occur from FY 2025 (specifically, the period beginning January 1, 2025, and ending September 30, 2025) through FY 2027. For a legislative summary of delays to the ACA’s Medicaid DSH reduction schedule, see MACPAC, “Disproportionate Share Hospital Payments,” July 2023, https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/disproportionate-share-hospital-payments/.

7 The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) estimates that the total state and federal reductions for 2026 and 2027 will be $14.2 billion each year compared to $8 billion in federal funds. To the extent states relied on providers through provider taxes and other means to finance the state share of DSH, the total (state and federal reduction) will be less. The U.S. Government Accountability Office estimated that state general funds as a source of revenue for DSH payments was 34 percent overall in 2018, but in many states a lower amount of state general funds were contributed to the state share. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Medicaid: CMS Needs More Information on States’ Financing and Payment Arrangements to Improve Oversight,” Report no. GAO-21-98, December 2020, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-98.

8 CRS, “Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Payments,” R42865, November 20, 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42865/21.

9 The $15 billion in total DSH spending does not include separate DSH payments made to institutions of mental diseases. MACPAC, “Medicaid Based and Supplemental Payments to Hospitals,” April 2024, Table 1, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Medicaid-Base-and-Supplemental-Payments-to-Hospitals.pdf.

10Kempski, Ann and Gee Bai, "Medicaid Financing Requires Reform: The North Carolina Case Study," Health Affairs Forefront, March 28, 2024, https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/medicaid-financing-requires-reform-north-carolina-case-study.

11Id. and North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, “North Carolina Medicaid Annual Report for State Fiscal Year 2023,” https://www.ncdhhs.gov/sl-2023-134-section-9e1-medicaid-annual-report/open.

12 MACPAC, “Chapter 3: Annual Analysis of Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Allotments to States,” March 2024, p. 74, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Chapter-3-Annual-Analysis-of-Medicaid-Disproportionate-Share-Hospital-Allotments-to-States.pdf.

13 MACPAC, “Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP; Chapter 1: Improving the Structure of Disproportionate Share Hospital Allotment Reductions,” March 2019, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/March-2019-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf.

14 Id.

15 Id. at 11.

16 See Mann, Cindy and Deborah Bachrach, “Integrating Medicaid Supplemental Payments into Value-Based Purchasing,” The Commonwealth Fund, November 22, 2016, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2016/nov/integrating-medicaid-supplemental-payments-value-based.