Actually, The SGR Has Slowed Health Care Cost Growth

To bolster their case against offsetting the high cost of SGR reform, many have claimed that the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) is “budget fakery” and represents “savings that aren’t going to be realized.” Yet while it’s true most SGR cuts have not gone into effect as scheduled, that doesn’t mean the SGR hasn’t helped to control health care costs.

In fact, through repeated temporary "doc fixes" to stave off the cuts by enacting more targeted savings elsewhere, the SGR has actually created nearly as much savings as it’s called for – albeit over a longer time period.

For a little bit of background, the SGR formula was created as part of the 1997 Balanced Budget Act to help control the rising cost of Medicare by essentially capping the growth of doctors’ payments. Since 2003, however, the SGR has called for cuts deemed too deep by Congress – and so they’ve used temporary “doc fixes” to replace these cuts with more targeted savings.

Despite these doc fixes, the SGR has actually done a great deal to control health care costs by keeping physician payment updates modest and pushing policymakers to offset the cost of avoiding cuts.

Our follow-up post, SGR Continues to Slow Health Care Cost Growth, updates the facts and figures in this blog in light of the 12-month "doc fix" passed in March 2014.

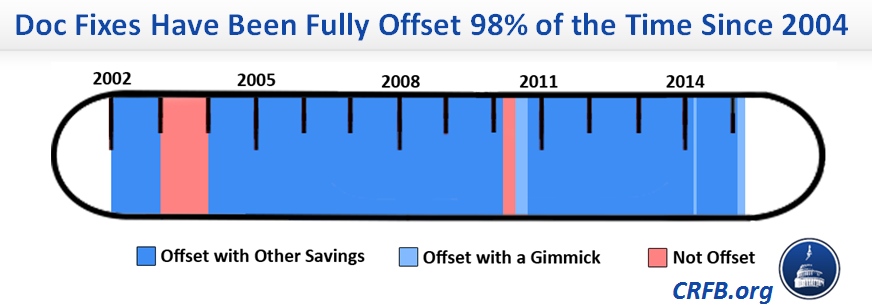

Lawmakers deficit-financed the first “doc fix” back in 2003, but since then have offset 120 out of the 123 months of doc fixes with equivalent savings. That’s 98 percent. Even ignoring the couple times small gimmicks were used, policymakers still paid for these delays 95 percent of the time – with almost all of those savings coming from health care programs.

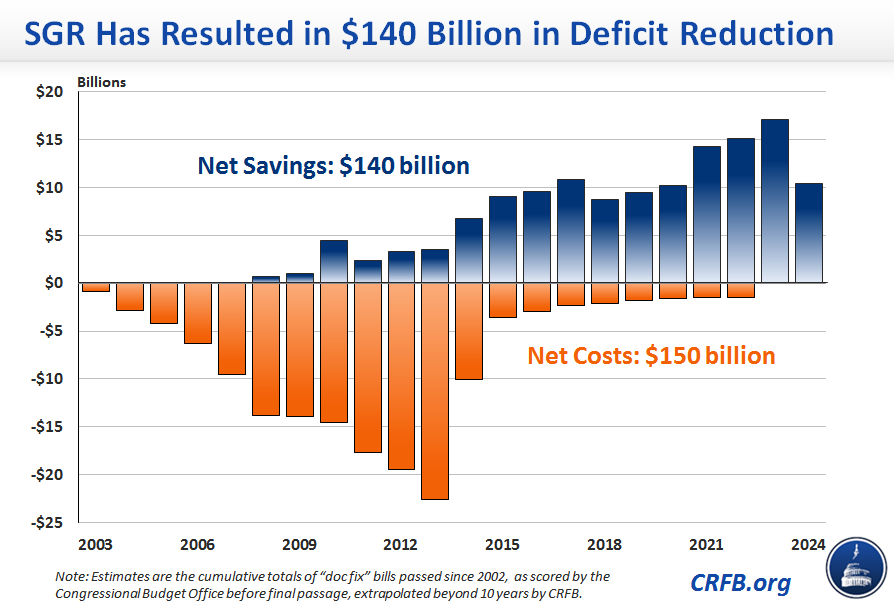

The fact that we almost always pay for temporary doc fixes matters both for understanding the fiscal history of the SGR and in determining its future. Since 2003, the total cost of “doc fixes” has added to just over $150 billion through 2024 – a fact bolstered by those who suggest no harm in adding a new $150 billion to the credit card. Yet those advocates forget that lawmakers have enacted $140 billion in deficit reduction over the same time period – almost entirely from health care programs – to pay for the repeated delays.

And despite implications to the contrary, these offsetting savings have often taken the form of serious, if small, health care reforms, saving taxpayers more than $130 billion from health care programs. Reforms have included expansions of bundled payments, equalizing payments for the same services done at different sites of care, more accurate payments for hospital services, bringing payments to Medicare Advantage plans more in line with the costs of traditional Medicare, recapturing unintended Affordable Care Act (ACA) premium subsidies, and reduced overpayments for services like clinical labs and advanced imaging. And then some of the savings have come from extending health care cuts already in place.

In addition, the threat of large payment cuts and the need to pay for “doc fixes” each year has likely encouraged lawmakers to avoid overly-generous payment updates for physicians in Medicare. While doctors have not received the huge cuts called for under the SGR, their payments have grown at an average of only 0.7 percent annually. By comparison, the Medicare Economic Index (MEI) has averaged 1.8 percent annual growth over that period.

Had we provided MEI-level updates over the last decade, costs would have been another $60 billion higher, which would bring the total savings resulting from the SGR to $200 billion. Assuming a payment freeze for the next decade, total costs through 2024 will be about $150 billion lower than if the MEI was adopted.

The bottom line – while the SGR has not worked exactly as originally intended, it has certainly helped to control health costs.

To be sure, the SGR is a flawed formula. And the fact that it has controlled costs does not mean lawmakers should continue the disruptive practice of enacting temporary patches – often for only months at a time. That’s why the bipartisan, bicameral legislation to replace the SGR with more sensible payment incentives is so encouraging.

But in enacting SGR reform, leaders cannot throw out the baby with the bath water. The package under consideration would cost at least $140 billion over ten years.

Replacing the SGR all at once offers an opportunity to pursue more structural Medicare reforms instead of tinkering on the margins. By changing payment models and incentives on the provider and beneficiary side, policymakers would not only be generating savings to pay for SGR reform, but also helping to strengthen Medicare, improve the health care system, and bend the health care cost curve.

Failing to pay for SGR reform, on the other hand, would not only break with precedent, it would break the bank as well.

Update April 1, 2014: The tables and graphs in this post have been updated to reflect the 12-month doc fix that the Senate passed on March 31.

Methodology Notes: To calculate the cumulative savings resulting from policies enacted to offset delays to the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula ($140 in total from 2003-2024), we analyzed Congressional Budget Office (CBO) scores of the relevant legislation. We allocated savings to costs based both on the score and our understanding of legislative history. For instance, although the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 increased the debt in total, lawmakers explicitly designated requisite health care savings to offset the costs of the "doc fix" included. In the multiple cases where deficit-reducing reforms were intended to offset both an SGR delay and a temporary extension of the various so-called "health extenders," we only counted the percentage of savings necessary to offset the SGR delay, and ignored the additional savings for the purposes of this analysis. The analysis does not incorporate the effects of doc fixes on federal interest costs. To estimate deficit savings beyond the 10-year windows estimated by CBO, we analyzed each policy separately, but for most we assumed that annual savings continued as the same percentage of their respective baseline. The estimates in this blog do not include either the savings achieved by the SGR reduction when it took effect in 2002 or the extrapolated costs of the deficit-financed SGR delay in 2003, due to a lack of data. Additionally, this analysis does not account for potential behavioral effects beyond those incorporated in CBO estimates that lower Medicare physician payment rates may have had in increasing the volume of physician services.