Actually, Paul, the Debt is Still a Problem

In a recent New York Times column, economist Paul Krugman argued that the focus on the national debt represented “an imaginary budget and debt crisis.” He stated that current debt increases are manageable, there is little danger of a debt crisis, and it would be “no big deal” economically to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio. He contends that those who focus on impending deficits are fear mongering and diverting the national attention "from its real problems — crippling unemployment, deteriorating infrastructure and more."

We find several flaws in Krugman’s budgetary logic, detailed below.

Claim: The Long-Term Outlook is "distinctly non-alarming"

In his column, Krugman argues that the latest Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections are "distinctly non-alarming" except to those engaging in scare tactics. We think Doug Elmendorf – Director of CBO – would disagree. In his recent testimony before the House Budget Committee, he warned that the debt projections could have "significant negative consequences," that further debt increases "could be especially harmful," and that the budget is on an "unsustainable current path."

Krugman's claim that the projections are benign is based on the fact that in 2039, debt as a share of GDP will only be as high as levels during World War II. Arguing debt is sustainable because it is projected to reach a level never before seen except once during a national catastrophe doesn't make sense. The debt buildup was sustained in part through financial repression and followed by a sustained period of economic recovery and (partially due to demographics) rapid growth. It was taken at a time when the United States was the only economic super-power and other economies were in shambles. Finally, it was taken with a clear plan and strategy to pay the debt in the future.

Whereas World War II was followed by years of near-balanced budgets, 2039 is currently projected to be followed by years of increasing deficits. By the end of the 75-year projection period, debt would equal nearly 230 percent of GDP. As CBO explains, this "could not be sustained indefinitely."

If this were not concerning enough, Krugman forgets to mention that the situation could be far worse. He focuses on CBO's current law baseline, which assumes that Congress does not pass any more doc fixes without gimmicky offsets (like this spring's), allows expired tax breaks to remain expired or be paid for (both the House and Senate have passed bills to revive them without offsets), and responsibly offsets all new legislation (unlike the Veterans Affairs reform or immigration funding bills now being considered).

If Congress acts irresponsibly, as we hope they will not, the situation would be far worse. Under CBO's "Alternative Fiscal Scenario" (AFS), debt would reach 163 percent of GDP by 2039, and above 250 percent of GDP after 2050.

Claim: A Debt Spiral is Almost Impossible

When the long-term outlook was released, Krugman argued that "CBO has just declared an end to the debt spiral." Specifically, he pointed out that with average interest rates lower than average growth, the federal government could simply remain in primary balance (keeping revenue equal to non-interest spending) and debt would fall as a share of GDP rather than increase.

Setting aside for a moment the fact the U.S. is never projected to reach primary balance, Krugman's original math was simply wrong. As Elmendorf explained (and Krugman subsequently corrected), interest rates after the first decade will be higher than nominal growth, not lower.

The 25-year averages originally cited by Krugman were especially influenced by the very low interest rates we expect in the next 5 years, and not a good indicator of long-term average. Indeed, when looking at the long-term interest and growth rates in the Long-Term Outlook, we find interest rates will be about 0.3 points higher than economic growth.

This was enough for Krugman to modify his assertion, updating it to assert that CBO's new assumptions only "almost eliminates the risk of a debt spiral." However, in the revised version he still forgets the impact that higher debt has on the economy.

CBO's long-term baseline scenario relies on "benchmark" economic assumptions that don't incorporate economic effects as its short-term scenario does. When CBO incorporates the fact that debt lowers growth and increases interest rates, the differential between the two rises from 0.3 to 0.8. Under the AFS, the gap widens further to nearly 1.8 points.

Under any of those scenarios, a debt spiral remains a very real possibility.

Growth and Interest Rates Over the Long-Term

| Without Economic Feedback | With Economic Feedback** | |||

| 25-Year Average (cited by Krugman) |

Long-Term Average | Current Law | Alternative Fiscal Scenario | |

| Nominal Interest Rate | 4.1% | 4.7% | 5.0% | 5.8% |

| Nominal Growth Rate | 4.3% | 4.4% | 4.2% | 4.0% |

| Difference | 0.2% | -0.3% | -0.8% | -1.8% |

Source: CBO, CRFB extrapolations

*The long-term average is based on CBO's estimates beyond the first decade (after 2025).

**CBO provided data on the feedback's effects on interest rates and GNP in 2039, which was used a rough proxy for the average rate change over the long term.

Claim: The Fiscal Gap is Tiny

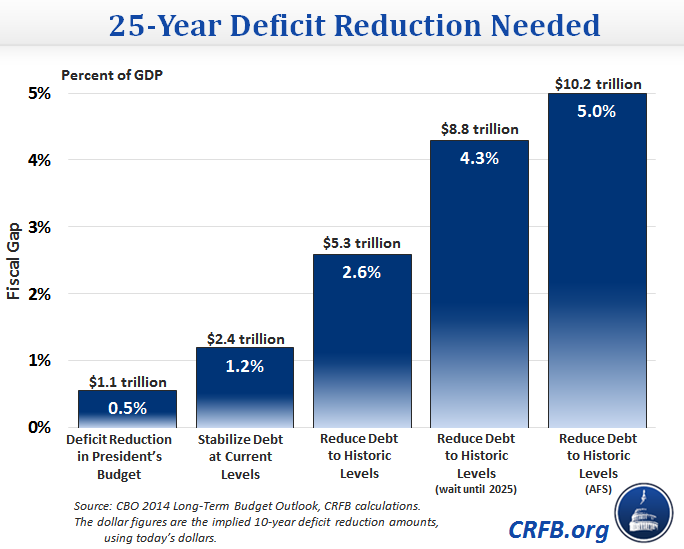

Krugman argues that the adjustments needed to stabilize debt are "surprising little" and "no big deal," totaling only 1.2 percent of GDP. Yet that would be the equivalent of about $2.4 trillion of savings over the next ten years, which is more than two times the savings in the President's budget, and far more than any policies we have seen proposed by Krugman to date. Indeed, when Erskine Bowles and Al Simpson proposed $2.4 trillion of revenue and targeted spending cuts and reforms – using much of that money to replace the sequester – Krugman suggested we should "disconnect that respirator [on the grand bargain], and let Bowles and Simpson spend more time with their families."

In fact, while he criticizes "Republican opposition to anything a Democratic president might propose," it appears to us that Krugman has opposed a large number of the President's past proposals as well, including means-testing Medicare, adopting the chained CPI, and adjusting the Medicare age.

Hard as it may be to achieve, even the 1.2 percent of GDP figure Krugman asserts is needed dramatically understates the case. A 1.2 percent of GDP adjustment would still leave the debt at record-high post-war levels; a 2.6 percent of GDP adjustment ($5.3 trillion over ten years) would be needed to bring it back to historical levels. That adjustment would increase to 5 percent of GDP ($10.2 trillion) if measured against CBO's AFS.

And as we've explained before, the longer we wait the harder it will be to close the fiscal gap. If we follow Krugman's advice and put the fiscal situation on the back burner until 2025, for example, the size of the adjustment to bring debt to historical levels would rise from 2.6 percent of GDP to 4.3.

Claim: Past Warnings About the Debt Were a False Alarm

Krugman argues that the debt crisis is an imagined crisis "promoted because it served a political purpose — that many people were pushing the notion of a debt crisis as a way to attack Social Security and Medicare." He concedes that previous debt projections were not entirely fear mongering – current estimates have improved somewhat because health care costs are slowing much more than anticipated. However, he does not acknowledge that some improvement is due to responses taken to address the debt crisis he dubs as imaginary. These responses were mostly deep cuts in the discretionary budget, most of which he opposed. In a rare point of agreement, we have also pointed out how these discretionary cuts were harmful and sidestepped the ultimate drivers of the long-term debt. However, the fiscal picture would be even worse today had these cuts not been adopted.

Claim: The consequences of debt are benign

Implicit throughout Krugman's entire piece is an argument that debt does not have serious consequences. As he said recently "I don’t want to say that debt doesn’t matter at all. But it clearly matters a lot less than the fear mongers tried to tell us." Yet the Congressional Budget Office repeatedly warns about the many consequences of debt – including slower economic growth, lower wages, higher interest rates, less room for public investment, reduced ability for the government to respond to future needs and crises, and an increased risk of fiscal crisis. As CBO explains:

How long the nation could sustain such growth in federal debt is impossible to predict with any confidence. At some point, investors would begin to doubt the government’s willingness or ability to pay its debt obligations, which would require the government to pay much higher interest costs to borrow money. Such a fiscal crisis would present policymakers with extremely difficult choices and would probably have a substantial negative impact on the country.

Even before that point was reached, the high and rising amount of federal debt that CBO projects under the extended baseline would have significant negative consequences for both the economy and the federal budget.

* * *

The debt crisis is not imaginary. If left untouched, debt will reach World War II levels within a quarter century, even assuming that policymakers turn over a new leaf of fiscal responsibility. It would be a mistake to let that happen, and debt could be much worse. The United States is not looking at a decade of balanced budgets and global dominance as we did in 1946. Even though deficits are under control for the next few years, they will not remain that way as demographic and health care pressures take over. It would be wise to act now to phase in targeted tax and spending changes now to put the nation's debt on a downward path over the long term.