Tax Reform in A Bipartisan Path Forward

Recent reports from Capitol Hill show momentum for tax reform is building. Both the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance Committees have been compiling options and draft reports on different aspects of tax reform, demonstrating a commitment from both tax-writing committees to examine the tax code. With the possibility of a conference committee for the budget resolutions that passed each chamber earlier this session, tax reform may be critical to a budget agreement.

With that in mind, we continue our series on A Bipartisan Path Forward by turning to the tax side of the budget to discuss the reforms proposed in Simpson and Bowles's new plan. Overall, they propose $740 billion in revenue over ten years, with $585 billion from tax reform. So how do they do it?

The plan would advance comprehensive tax reform that lower rates and broadens the tax base to raise revenue. It specifically mentions five parameters for reform:

- Lower rates, broaden the base, and reduce deficits.

- Start from zero, a tax system with no tax expenditures, and raise rates accordingly when tax expenditures are added back in.

- Maintain or increase progressivity of the tax code.

- Move to a territorial tax system.

- Promote economic growth and competitiveness.

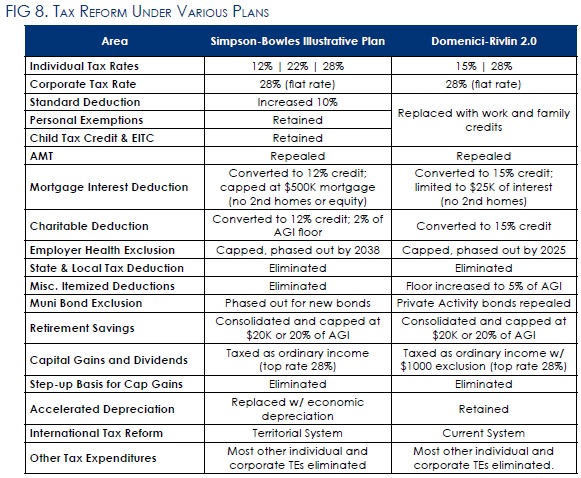

Many of these points are familiar ones from the original Simpson-Bowles plan. In order to hit its revenue target, the plan started with a clean slate of zero tax expenditures, three tax rates of 8, 14, and 23 percent, a repeal of the Alternative Minimum Tax, and a corporate rate of 26 percent (see what it would take to get to a 26 percent corporate rate with our tax calculator). The Illustrative Plan in the original Simpson-Bowles then added back preferences like the Earned Income Tax Credit and child tax credit, while retaining the employer health insurance exclusion, mortgage interest deduction, charitable deduction, and retirement savings preferences in more limited forms. It raised the individual rates to 12, 22, and 28 percent and the corporate rate to 28 percent to compensate. Due to changes in the tax code, economic forecasts, and revenue targets since the original Simpson-Bowles plan came out, a plan modeled on the Illustrative Plan would differ somewhat from the one described above.

To enforce the revenue targets in case tax reform does not come to fruition and to incent lawmakers to take up reform, the plan calls for an enforcement mechanism to raise the $585 billion of revenue. One approach the report cites is to have a broad limitation on tax expenditures. It estimates that a rate limit (similar to one in the President's budget) of 27 percent applied to all itemized deductions, certain above-the-line deductions, the standard deduction, the health insurance exclusion, the foreign income exclusion, and the municipal bond exclusion would roughly raise the revenue targeted. An alternate failsafe which would more closely mimic actual tax reform would have a different limit on tax expenditures, such as the Feldstein-Feenberg-MacGuineas cap, that raised more revenue, with half the revenue used to hit the revenue target and the other half applied to rate reduction. This is very similar to a tax reform failsafe proposed by Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer, using the logic of a "50 percent solution" that splits the difference between revenue-neutral 1986-style reform and the President's reforms that would go solely to deficit reduction. Certainly, lawmakers could make individual changes in the tax code in addition to the mechanisms mentioned in the report.

Tax reform may be the key to getting bipartisan agreement on a budget deal, and "A Bipartisan Path Forward," like the original Simpson-Bowles plan, presents a bold, pro-growth approach to accomplishing it.