New Simpson-Bowles Plan Would Boost Economic Growth, Not Slow It

Some commentators have criticized deficit reduction plans like "A Bipartisan Path Forward" for, in their opinion, promoting austerity at a time when we should be promoting economic recovery. Missing from their analysis is that many deficit reduction plans -- the recent one by Erskine Bowles and Al Simpson included -- would actually reduce short-term austerity when the economy is weak and implement the vast majority of its deficit reduction in later years when the economy is stronger.

Indeed, just behind putting the debt on a downward path, the second principle put forward by Erskine Bowles and Al Simpson is to "Promote, Don't Disrupt, Economic Growth." They write:

The United States must pursue a growth agenda. As the economy recovers, one of the best ways to promote economic growth is to bring our debt under control to encourage private investment and mitigate the risk of a fiscal crisis. However, sharp austerity could have the opposite effect by tempering the still fragile economic recovery. In order to protect the recovery and promote long-term growth, deficit reduction should be phased in gradually and reforms should be designed to strengthen current economic conditions, promote work, encourage innovation, improve productivity, and bolster investment in our future. Encouraging investment also means finding additional savings from wasteful or low-priority spending throughout the budget to make resources available for critical investments in education, high-value research and development, and infrastructure to meet the demands of the future.

And while most of the policies in the plan begin in 2014, they are phased in quite gradually. Of the $2.5 trillion of total deficit reduction, only about 5 percent of it takes place before 2016 when the economy is still expected to be relatively weak. By comparison, a full 20 percent of the sequestration savings occur before 2016. As a result of these differences, the Bipartisan Path Forward actually represents less of a hit on the economy in 2013, 2014, and 2015 -- even as it reduces the deficit by more than twice as much over ten years.

[chart:8577]

Relative to the Congressional Budget Office current law baseline, the fact that the Simpson-Bowles plan repeals much of the sequester should lead to a larger economy in 2013 and 2014, likely in the range of 0.2 or 0.3 percent. The larger deficit reduction over the decade would lead to additional growth as the economy recovers (with a small possible hit to the economy in the middle of the decade), as would pursuing comprehensive tax reform.

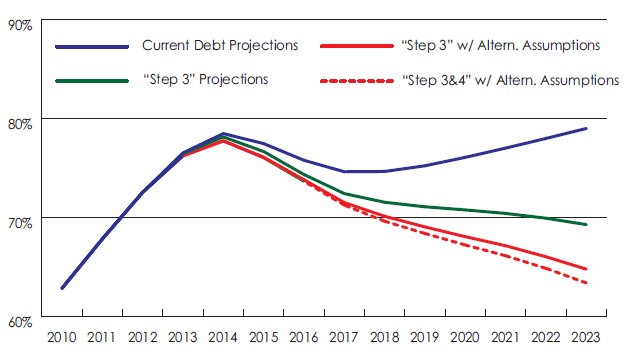

In Appendix E of the report is an attempt to analyze the potential growth effects of the Simpson-Bowles plan and the resulting "fiscal dividend" -- essentially the additional revenue generated by faster economic growth. Whereas the plan would reduce debt levels to 69 percent of GDP under traditional scoring, the report finds that assuming a faster war drawdown and applying some conservative dynamic scoring would result in debt levels falling to 65 percent of GDP.

Source: A Bipartisan Path Forward

How do they reach this result? First, they assume $380 billion less in spending on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan over the next decade, consistent with the Senate budget resolution, to reduce the debt from 69 percent of GDP to 68 percent of GDP.

Next, they attempt to measure the economic effect of less deficit reduction now and more in the future using CBO's report, Macroeconomic Effects of Alternative Budgetary Paths (we blogged on it earlier this year) which finds a generic $2.3 trillion deficit reduction plan would increase GDP by 0.5 percent and GNP by 0.9 percent by 2023.

Finally, they attempt to estimate the effects of comprehensive tax reform on economic growth. The Joint Committee on Taxation has estimated that the combined effect of generic base-broadening reforms to both the corporate and individual code could increase output by anywhere from 1.2 percent to 2.0 percent in the second five years after enactment. The analysis conservatively assumes a one percent increase in the latter half of the ten-year macrodynamic projection.

These economic adjustments, taken together, would likely increase revenue by about $375 billion and generate another $120 billion of interest savings. Combined with the higher GDP level in the denominator, this would be enough to bring debt levels down to 65 percent of GDP by 2023.

The Bipartisan Path Forward does not endorse this type of dynamic scoring as a normal budget convention -- we've written before about the pros and cons of such an approach -- but that doesn't mean growth effects should be ignored. By replacing the abrupt mindless sequester with more intelligent, gradual, and ultimately larger deficit reduction measures it is possible to improve the short- and long-term economy and in the process further control our mounting debt. While dynamic economic effects are difficult to estimate, these estimates show that the Simpson-Bowles proposal could both promote economic growth and reduce debt even further than advertised.