The Tax Break-Down: The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

This is the fourteenth post in our blog series, The Tax Break-Down, which will analyze and review tax breaks under discussion as part of tax reform. Last week, we wrote about the FICA Tip Credit.

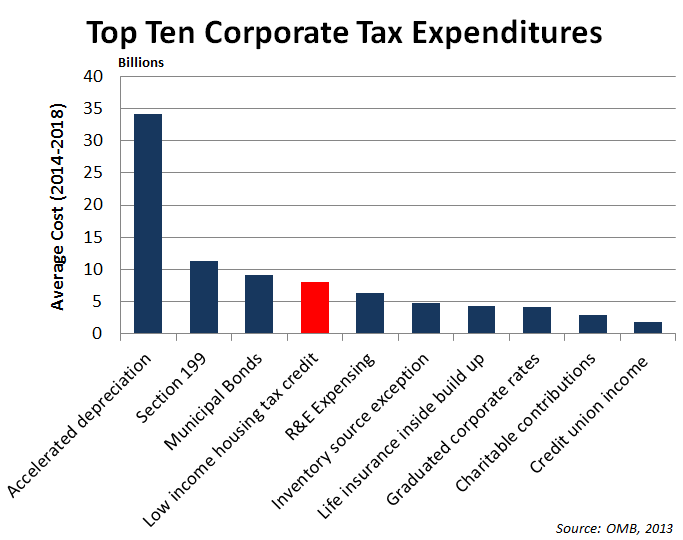

The low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) is the fourth most expensive corporate tax break, and was enacted as part of the 1986 tax code overhaul. The LIHTC is the federal government's largest tax expenditure targeting affordable rental housing and (when enacted) represented a new approach to tax expenditures, rather than relying on direct subsidization.

Under the LIHTC, the government allocates nonrefundable tax credits to state-run housing agencies, who distribute them to housing developers that agree to make a portion of their units available to low-income renters. The housing developers who receive the tax credits then sell them to independent investors to help finance the actual development of the housing units. The investors are ultimately the ones who claim the tax credit rather than the low-income residents of the rental units or the developers.

There are actually two tax credits under the program: a 9 percent credit allocated to new construction projects and a 4 percent tax credit for new construction and rehabilitation projects financed with tax-exempt private activity bonds. Under current law, the 9 percent credit is scheduled to revert back to more uncertain and fluctuating rates next year based on formulas in effect in 2008 — although this provision has a very negligible budget impact. The 9 percent credits are allocated across all 50 states based on population, about $2.20 per person in 2012, which is indexed to inflation each year. For low population states, there is an allocation floor slightly over $2.5 million.

How Much Does It Cost?

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, the LIHTC will cost $6.7 billion in foregone revenue in 2014, or approximately $85 billion over the next ten years. Likewise, OMB estimates that the LIHTC will reduce revenues to the federal government by an average of about $8 billion each year over the next few years. Corporations claim 95 percent of the credit, with individuals and passthrough businesses claiming the remainder.

According to CRFB's Corporate Tax Reform Calculator, eliminating the LIHTC could finance a roughly 0.3 percentage point reduction in the corporate tax rate.

The costs of the LIHTC are roughly a third of the size of outlays for Section 8 housing vouchers. A large share of LIHTC credits (specifically, the 9 percent credits) are capped based on the per-capita allotment to state housing agencies each year and, therefore, provide a set amount of federal funding committed to support low-income housing, unlike support given through other programs, which can vary from year-to-year.

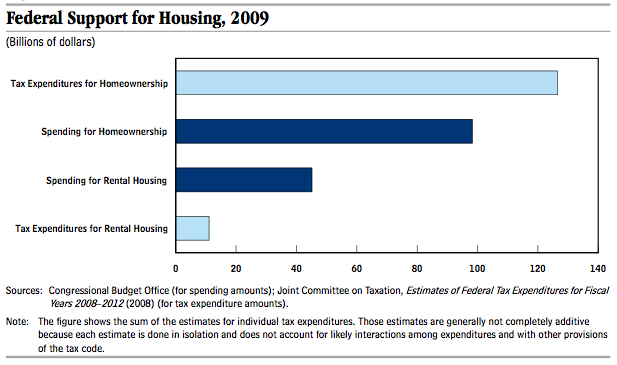

In terms of overall federal support for housing, including rental housing and home ownership, the LIHTC makes up only a small share of the resources. Data from 2009 from the Congressional Budget Office shows that tax expenditures for rental housing (of which the LIHTC comprises roughly half) were much smaller than federal support for homeownership and even spending on rental housing. (Note: Spending and tax expenditure costs were likely larger in 2009 than in other years as a result of temporary measures, such as the Making Home Affordable program and first-time homebuyer credit.)

Who Does It Affect?

The LIHTC affects developers seeking to build low-income housing units by affecting their access to capital, the investors who ultimately receive the tax credits, and low-income households who may ultimately have greater access to affordable rental housing as a result of the tax credits.

The final rental housing units are meant to serve households with incomes at or below 60 percent of median income in the local community.

The final investors can be individuals, corporations, or financial institutions. Since about 2001, the entities claiming of the majority of the credits shifted from individual investors to corporate investors. One dollar of tax credit allows an investor to claim the tax credit each year for a 10-year period once the project is completed.

According to some estimates, the LIHTC has helped produce 2.6 million housing units for lower-income households, creating over 3.6 million jobs and leveraging $100 billion in private capital. However, data suggests a muted impact overall on the net supply of affordable housing.

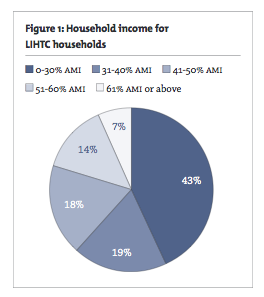

In terms of tenant data, in 2008 the government began requiring state housing agencies to provide tenant data to HUD, which made a statisical sample available to researchers. Some initial studies show that the tenants of LIHTC units tend to have slightly higher incomes than other federal rental assistance programs, but that more than 40 percent of LIHTC units had occupants who earned 30 percent or less of area median income (a threshold referred to as "extremely low-income" households).

Source: Moelis Institute, NYU.

What Are the Arguments for and Against the LIHTC?

Proponents of the LIHTC include a broad political coalition of developers, intermediaries, and housing advocates. Since the LIHTC brings in potential investors and developers into the low-income housing market who may otherwise not have been involved in the market, proponents argue that it creates a greater supply of housing for households facing few affordable options. The LIHTC has had a better record than other types of public assistance programs in providing affordable housing outside areas of concentrated poverty.

Also, housing experts often point to the flexibility that states have in setting regulations, responding to shifting housing trends, and administering the tax credits to developers — leading to innovations that would be more difficult at a federal level. Additionally, there may political advantages in giving broad authority to state housing authorities instead of the federal government.

Opponents of the LIHTC argue that providing credits does not guarantee affordable housing will actually be constructed, since credit prices and housing supply fluctuate with the economy. For instance, during the recent financial crisis, the market value of the tax credits among potential investors fell sharply as a result of lower risk tolerance (particularly risk that economic changes could wipe away tax liability and, thus, the benefit of LIHTCs) and investors had fewer available funds to invest. As a result, developers faced significant challenges in obtaining financing for developing low-income housing units. Low-income households faced a cutback in supply at the same time that demand for affordable rental housing was increasing as a result of increased unemployment, increased difficulties in obtaining a mortgage, and increased foreclosure rates.

Other opponents have raised efficiency concerns by noting that there are sizable transaction costs associated with the sale of the tax credits, which often flow through independent third parties that help oversee the transactions and compliance regulations, along with an overall complex system to run at all levels. Some estimates peg the total amount of initial equity provided for construction projects falling to roughly 71 percent after transaction and contract costs are factored in, though there is reason to believe competition in recent years has pushed these costs down.

According to available evidence, the LIHTC program may "crowd out" sizable shares of other unsubsidized housing and, thereby, has limited effects on the overall supply of affordable housing. But other research has argued that shortages of affordable housing will dampen this result, as can other factors.

Lastly, many residents in housing units financed in part through LIHTC's often receive other forms of public housing assistance, such as Section 8 vouchers. As a result, it is unclear whether the tax credits are successful in isolation and if subsidies alone could address the challenges of affordable housing.

What Are the Options for Reform and What Have Other Plans Done?

The two large bipartisan deficit reduction plans, the Fiscal Commission and Domenici-Rivlin proposals would both eliminate the low income housing tax credit in favor of lower rates. Stopping the credit allocations to all new projects would raise approximately $40 billion.

Many other proposals would keep the basic structure of the LIHTC in place, but make improvements around the edges. For instance, the President's budget would adjust several parameters of the LIHTC by allowing states to convert unused private activity bonds into LIHTCs that states can allocate and encouraging mixed-income occupancy projects, among a few other small reforms.

Many LIHTC reform proposals would look to replace the tax credits with a voucher program; however, vouchers typically come with a host of other challenges, including higher overall prices for housing given the federal subsidies and the potential reduced supply of affordable housing for lower income households who have limited means but do not qualify for vouchers.

There have also been calls for lawmakers retain the credit in its current form or to expand the LIHTC or other federal programs aimed at promoting affordable housing to better serve even lower-income households. However, some suggest these goals could be better met through initiatives intended to serve more at-risk households, such as the National Housing Trust Fund.

| Revenue Impact from Reform Options for the LIHTC | |

| Policy | 2014-2023 Savings |

| Fully eliminate the LIHTC for new and existing credits | $85 billion |

| Eliminate new LIHTC allocations (but honor existing credits) | $40 billion |

| Eliminate new LIHTC allocations, for C-Corps only | $38 billion |

| Replace LIHTC with increased voucher spending for low-income renters | Dialable |

| Reduce LIHTC credit percentage to 8 percent or lower | Unknown (Reduces deficit) |

| Replace LIHTC with a tax reduction on rental income | $0 billion |

| Adopt a renters tax credit |

Dialable |

| Reallocate tax credits to states according to need | Neutral |

| Cap the number of rent-restricted households in each LIHTC property | Unknown |

| Allow LIHTC credits to be used against AMT liability | Unknown (Increases deficit) |

| Adopt President's proposal (convert PAB cap to LIHTCs, encourage mixed income occupancy, formula changes, etc.) | -$1 billion |

| Increase LIHTC annual allocations by 50 percent | -$12 billion |

Where Can I Read More?

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development — LIHTC Basics

- Congressional Research Service — An Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

- Mihir Desai, Dhammika Dharmapala, and Monica Singhal — Tax Incentives for Affordable Housing: The Low Income Housing Tax Credit

- Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University — Long-Term Low Income Housing Tax Credit Policy Questions

- Len Burman and Alastair McFarlane —The low-income housing tax credit

* * * * *

The LIHTC is a substantial component of the federal goverment's effort to promote affordable housing, and is one of the larger corporate tax expenditures. But there are many federal housing programs — including public assistance programs, housing vouchers, and other housing tax incentives — and some may be more effective than others at fostering access and greater supply of affordable housing for lower-income households. As lawmakers in both the House and Senate look to overhaul and simplify the federal tax code, they will have to consider how to treat the LIHTC in the pool of hundreds of other reforms.

Read more posts in The Tax Break-Down here.

Update April 29, 2014: The original version of this post stated that HUD had not yet published tenant information it collected from state housing agencies. The post has been updated to state that HUD has posted a statisical sample of the data for housing researchers.