The Tax Break-Down: Foreign Earned Income Exclusion

This is the twelfth post in our blog series, The Tax Break-Down, which will analyze and review tax breaks under discussion as part of tax reform. Last week, we wrote about intangible drilling costs, a tax break for companies in extractive industries.

The United States is the only major industrialized nation that taxes citizens on their worldwide income. If an American lives abroad, they owe taxes to both the country they are living in and the United States, but they can claim a credit to avoid double taxation and pay whichever is higher. All other developed countries do not tax their citizens abroad—those citizens only owe tax to the country they are living in.

The foreign earned income exclusion, sometimes referred to as Section 911, allows U.S. citizens and resident aliens to exclude the first $97,600 (indexed for inflation) of foreign earned income, so that money is only taxed by the country of residence, not the United States. There is also a related exclusion for housing allowances paid by an employer (or a deduction for self-employed housing expenses), which are limited to 30 percent of the income exclusion.

These benefits are in addition to the foreign tax credit that prevents the same income from being taxed by two countries, which is not considered a tax expenditure. Federal employees do not benefit from these exclusions, but they do get a separate set of tax benefits. Federal employees are generally not taxed by other countries and pay tax only to the United States, although amounts recieved for cost-of-living, housing, and travel are excluded from income.

The foreign earned income exclusion is designed to prevent a U.S. taxpayer who moves to a high-cost country from paying more taxes than a similarly situated taxpayer in the United States, since the standard deductions are not adjusted for a higher cost country. The taxpayer living overseas is likely to have to have a higher income and higher expenses to obtain the same quality of life. The exclusions do not matter to a U.S. citizen living in a high-tax country, since they earn enough foreign tax credits not to pay any U.S. tax. However, U.S. citizens in low tax countries could pay little to no income tax due to these exclusions.

The income exclusion's parameters and limit have changed numerous times since its introduction in 1926. From then until 1962, the exclusion was unlimited, after which it was set at $20,000 in the Revenue Act of 1962. The limit was changed numerous times in the 1980s, eventually settling at $70,000 as set in the Tax Reform Act of 1986. The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 called for the limit to be indexed for inflation, a policy that went into effect in 2006.

How Much Does It Cost?

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, the income and housing exclusions will cost $6 billion in 2014, or approximately $90 billion over the next ten years. Most of that cost (84 percent) is from the income exclusion. The Office of Management and Budget has a similar estimate: $6 billion in 2014.

A JCT score of the 2010 Wyden-Gregg tax reform bill estimates that repealing the exclusions would raise $69 billion from 2011-2020. The Congressional Progressive Caucus estimates repeal would save $75 billion in the current 2014-2023 window.

Who Does It Affect?

Obviously, the exclusions are for U.S. citizens who live for an extended period outside the U.S. In terms of the distributional effects, those who benefit from the exclusions have much higher income on average than the overall population. Using IRS data, Eric Toder of the Tax Policy Center finds that in 2006, the average income for someone who used the exclusions was $170,000, compared to the overall average of $58,000.

Average Income per Tax Return by Adjusted Gross Income, 2006

Source: TPC

Note: X-axis represents adjusted gross income, while Y-axis represents income with the FEIE added back in.

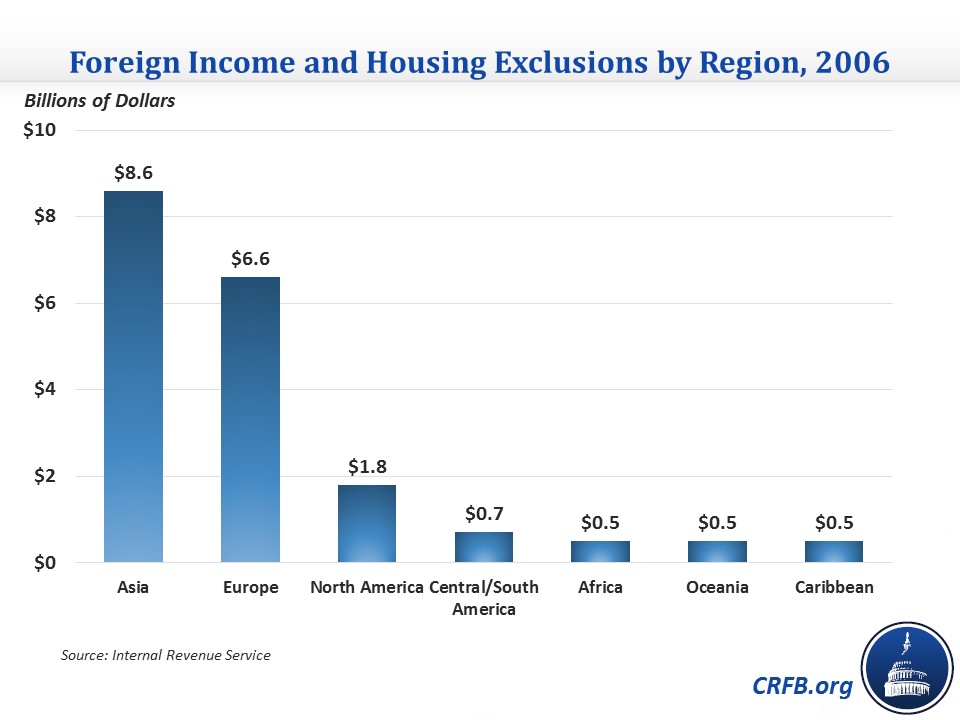

In terms of geographical location, in 2006, there were $20 billion in exclusions/housing allowances claimed, with the most coming from Asia ($8.6 billion, about one-quarter coming from Iraq and Japan). The second most came from Europe ($6.6 billion), and the third most came from other North American countries ($1.8 billion). Other regions/continents accounted for less than $1 billion each.

What Are the Arguments for and Against the Exclusions?

Proponents of keeping the foreign earned income exclusion and housing allowance argue that the provisions are necessary to align U.S. taxation with that of other industrialized nations who do not tax their citizens who live abroad. They also argue that they do not benefit from U.S. government services and so should not pay for them. Proponents also point out that exclusions adjust for higher costs of living abroad and level the playing field for U.S.-based multinationals that hire workers from home, since foreign expatriates working for a foreign multinational are not taxed by their home country. Further, they argue that reducing or eliminating the exclusion would make it more burdensome for U.S. citizens to conduct business or hold a job abroad, thus limiting the ability of U.S. owned businesses to compete. Finally, proponents claim that the exclusions help alleviate double taxation.

Opponents of the exclusion argue it is unfair to give Americans tax breaks for choosing to work abroad, subsidizing their lifestyle choice. Because many companies offer "tax equalization" packages promising employers that they will not pay any more tax overseas than they would pay in the United States, the exclusions subside employers sending employees overseas. They point out that U.S. citizens do still receive government benefits, such as through the U.S. military's presence abroad. They also say that the exclusions are an overly blunt way of correcting for the high costs of living abroad, since they also provide benefits to people living in countries with lower costs than the U.S.

What Are the Options for Reform?

The foreign earned income exclusion has been a frequent target for repeal in bills and other plans over the years. As an example, the Wyden-Gregg bill, Congressional Progressive Caucus budget, Simpson-Bowles plan, and Domenici-Rivlin plan all call for the exclusion to be eliminated. The President's submission to the Super Committee included the income exclusion as part of the 28 percent limit on certain tax preferences, thus limiting its benefit for taxpayers in the 33, 35, and 39.6 percent tax brackets.

On the other side, in 2008, a group of House Republicans introduced legislation to make the foreign earned income exclusion unlimited. This would transform the U.S. tax code for individuals from a citizenship-based system to residence-based system, where only people residing in the U.S. would be taxed by the federal government. A variant on this idea from Bernard Schneider would apply an "exit tax" regime in place of the current system. This system would apply a tax on a person's property who takes residence abroad, after which they would be exempt entirely from U.S. taxation.

Of course, there are many other options for reform, including changing the limit amount, freezing it so it does not rise with inflation, or subjecting it to another broad-based tax expenditure limit other than the 28 percent limit.

| Options for Reforming the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (2014-2023) | |

| Policy | Savings |

| Repeal the income and housing exclusions | $90 billion |

| Reduce exclusions by half | $35 billion |

| Repeal the income exclusion | $75 billion |

| Repeal the housing exclusion | $15 billion |

| Limit the value of the exclusion to 28% | $5 billion |

| Freeze the exclusion amounts so they cannot grow with inflation | $5 billion |

| Make the exclusion unlimited | -$10 billion |

| Replace the exclusion with an exit tax | Dialable |

Note: Estimates are based on available scores or very rough CRFB estimates.

Where Can I Read More?

- Internal Revenue Service -- Foreign Earned Income Exclusion

- Internal Revenue Service -- SOI Tax Stats - Individual Foreign Earned Income/Foreign Tax Credit

- Eric Toder -- Taxes on Foreign Income

- Congressional Research Service -- Tax Expenditures: Compendium of Background Material on Individual Provisions (starting PDF p. 51)

- FAWCO -- Foreign Earned Income Exclusion In the Crosshairs - Once Again!

- American Bar Association -- Report of the Task Force on International Tax Reform

- Bernard Schenider -- The End of Taxation without End: A New Tax Regime for U.S. Expatriates

- PriceWaterhouseCoopers -- Economic Analysis of the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion

*****

While discussion of the international tax system usually focuses on how businesses are taxed, there is also a question of how individuals should be treated. The foreign earned income exclusion serves as a way to account for higher cost-of-living countries. However, it may not be the best way to reflect differences in cost of living, since it doesn't account for lower cost-of-living countries, and completely eliminates income tax liability for some U.S. citizens in low-tax countries. Lawmakers will have to decide whether the exclusion is worth keeping or whether it is worth scaling back or eliminating for deficit or rate reduction.