Social Security Cost Growth Should Be Slowed, Not Accelerated

In a speech in Elkhart, Indiana on June 1, President Obama discussed retirement security, saying, "We can’t afford to weaken Social Security. We should be strengthening Social Security. And not only do we need to strengthen its long-term health, it’s time we finally made Social Security more generous, and increased its benefits so that today’s retirees and future generations get the dignified retirement that they’ve earned. And we could start paying for it by asking the wealthiest Americans to contribute a little bit more. They can afford it. I can afford it."

He did not specify what the expanded benefits or tax increases would look like, but broad-based benefit increases would not be the best use of resources and would put the cart before the horse in terms of ensuring solvency. In addition, increasing taxes on the rich would help Social Security's finances but would not fully ensure 75-year solvency and would become a more inadequate solution over time, especially if it is enacted along with benefit increases.

The Opportunity Cost of Increasing Social Security Spending

Targeted benefit enhancements for Social Security recipients who need them most certainly should be considered in the context of a reform plan, and indeed they have been included in a number of bipartisan plans put forward in recent years.

But before advocating for broad expansions that would increase overall costs, policymakers must recognize that both costs and benefits are already growing rapidly. As recently as 2008, the program's costs consumed only 11.6 percent of payroll, well below the nearly 13 percent raised by the payroll tax and other sources. By 2035, that cost will grow to 16.6 percent according to the Social Security Trustees and almost 19 percent according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Both the number of beneficiaries and benefit levels (as we discuss below) will grow significantly over time.

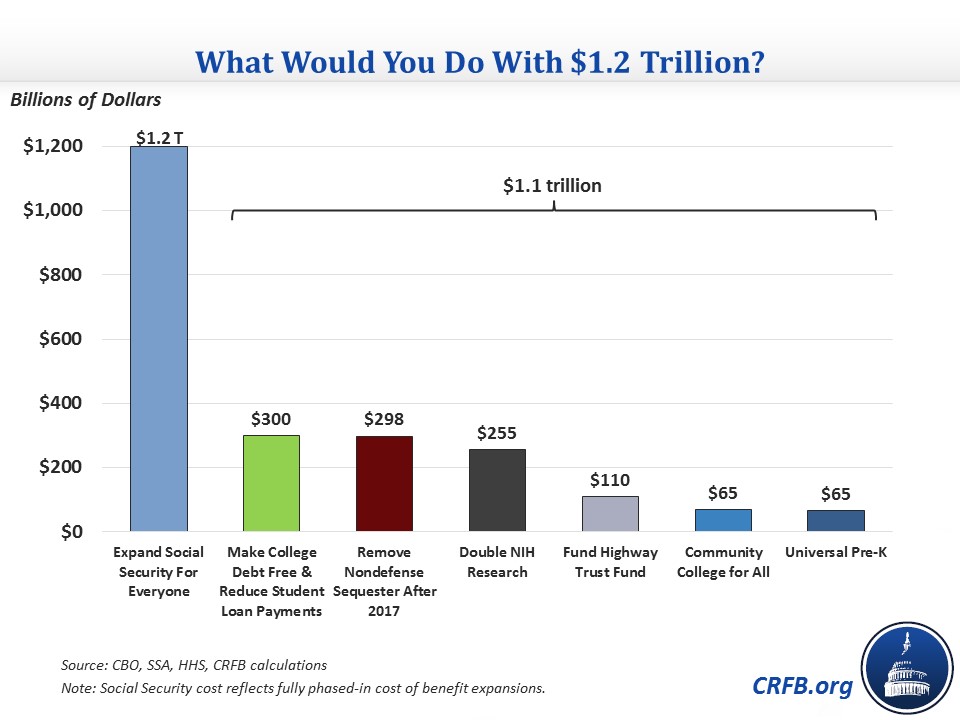

In light of the benefit growth under current law – which greatly outpaces the growth in available revenue – it is far from clear that further net increases are a wise use of scarce dollars, particularly since broad-based expansions can be quite costly. Democratic presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders's (I-VT) Social Security benefit expansions, as one example, would cost 1.3 to 1.4 percent of payroll once fully phased in, the equivalent of at least $1.2 trillion over ten years. For that cost, it would be possible to fully repeal the non-defense sequester, make college debt-free, double National Institutes of Health research funding, make community college free, establish universal pre-K, and fully fund the Highway Trust Fund.

Whereas those options would all increase investment-oriented spending and spending in children, increases in Social Security would actually exacerbate the trend away from spending on investments and on children. According to the Urban Institute’s Kids' Share report, the federal government spent six times as much on seniors as children (in 2011), and that trend will surely grow under current law with three-fifths of total spending growth over the next decade coming from adults and seniors on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid but only two percent from programs for children. Broadly expanding Social Security benefits would give seniors first claim on additional tax revenues and therefore worsen this disparity.

Moreover, broad-based benefit increases could actually provide greater benefits (in dollars) to the most affluent retirees since they have higher benefits already and they tend to live longer. Under Senator Sanders's plan, for example, Social Security would spend $42 billion a year more for the wealthiest 20 percent of earners, but only $8 billion for the lowest quintile, according to Third Way.

Lawmakers must weigh benefit expansions against other priorities, keeping in mind the economic, fiscal, and distributional consequences of their decisions.

Do Most Seniors Need Higher Benefits?

Currently, about 8 percent of Social Security beneficiaries age 62 and older live in poverty, and 13 percent of beneficiaries have incomes less than 125 percent of the poverty line. Certainly more could be done to enhance benefits for these and other vulnerable populations; for example, by creating a new minimum benefit, making the benefit formula more progressive, and/or expanding benefits for widow(er)s. But the case for broad-based benefit expansions – including for very wealthy beneficiaries – seems weak.

As we showed last year, average retirement income in the United States is among the highest in the world – higher than all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries other than Luxembourg (more recent estimates from Andrew Biggs find that Norway also has higher income).

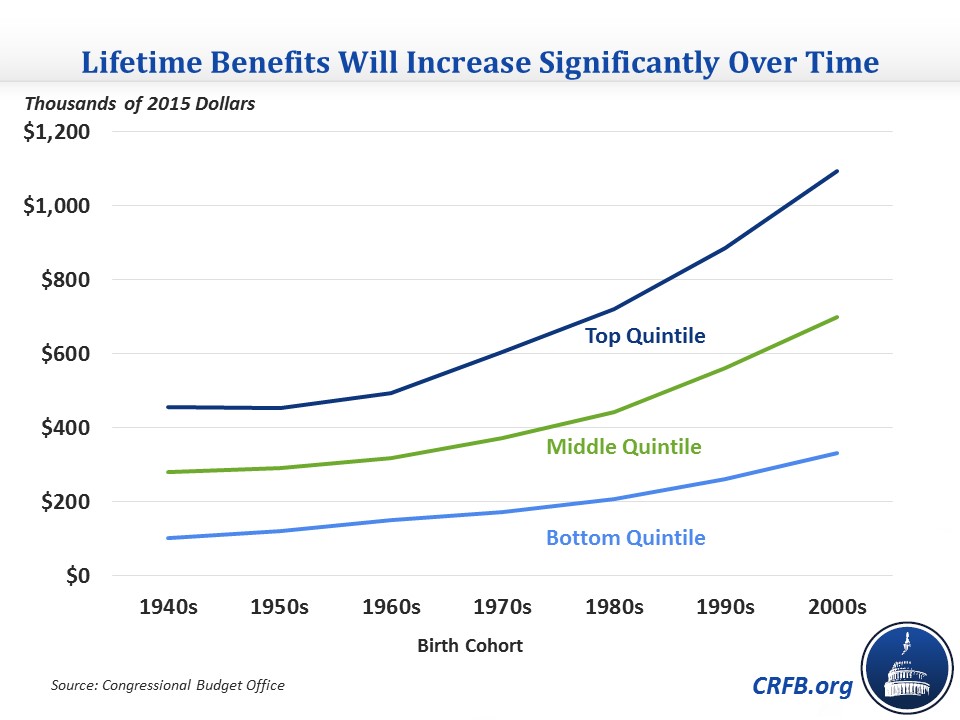

And at least when it comes to Social Security, that income is projected to grow. Initial Social Security benefits themselves rise roughly in line with wage growth, and lifetime benefits increase further as life expectancy grows.

A typical recent retiree born in the 1940s, according to CBO, will receive about $18,000 per year in initial benefits and $280,000 of benefits over their lifetime. Annual scheduled benefits for someone born in the 2000s, meanwhile, will be nearly twice as high (in constant 2015 dollars) at $35,000 initially and almost $700,000 over their lifetime. For the top one-fifth of earners, the increase is even sharper: annual benefits over the period will rise from $24,000 to $52,000 initially and lifetime benefits from $455,000 to nearly $1.1 million.

And of course, this is only for individuals. Generally, Social Security guarantees that a couple earns at least 1.5 times as much as the higher earner in that couple and up to twice as much.

Given that Social Security benefits are already growing rapidly – so much so that revenue will cover only about three-quarters of costs – it is reasonable to question whether further expanding benefits for middle- and higher-earners is really a wise use of resources.

The Limits of Taxing the Rich

Lawmakers also must assess their desire to increase overall spending on Social Security in the context of the program's finances. President Obama suggests taxing high-income earners to improve Social Security's finances. Certainly this can be a part of any solution of fix Social Security, but there are limits to this strategy.

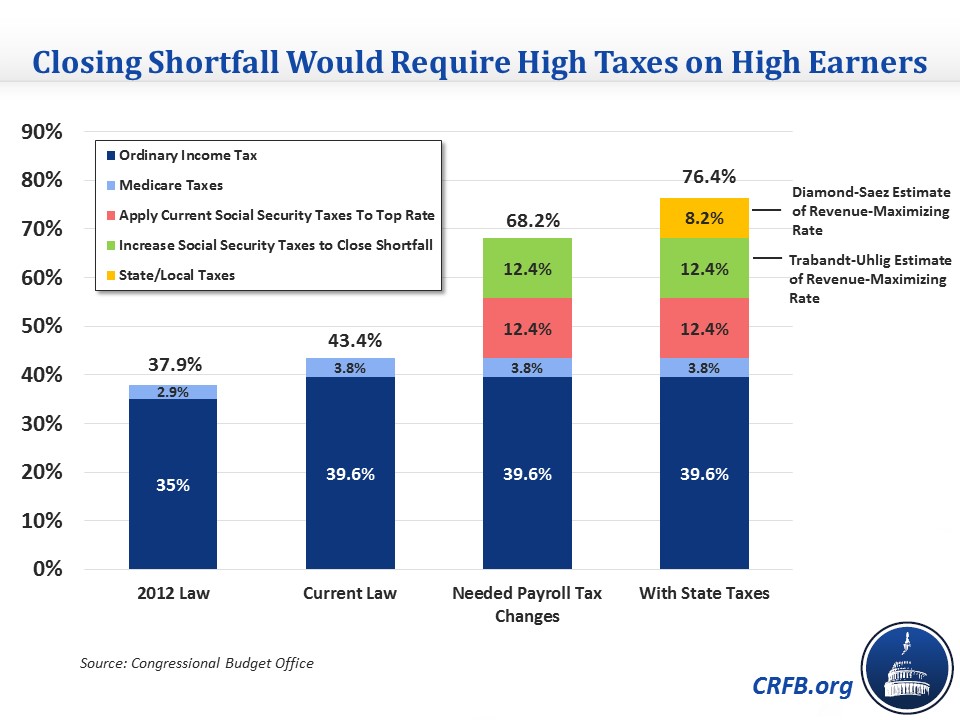

Senator Sanders, for example, would pay for his plan by applying the 12.4 percent payroll tax (currently imposed on the first $118,500 of wages) to all income above $250,000 and then applying an additional 6.2 percent tax on investment income above that level. Yet under Senator Sanders's plan, Social Security’s trust fund would only be extended by 40 years, and by the end of the 75-year window Social Security would face an annual deficit of nearly 2.5 percent of payroll. Closing that gap further with taxes on high earners would eventually require more than doubling the payroll tax rate for high earners (assuming no additional money from investment income, as capital gains would already be past their revenue-maximizing limit), bringing the total tax hike to about 25 percent for those earners.

Combined with current taxes, a 25 percent hike would bring the top statutory rate to about 68 percent – or an average of 76 percent including state and local taxes but excluding interactions. With estimates of the revenue-maximizing rate in the 60s or low 70s, such tax hikes would leave little room to tax the wealthy for anything else, and it could create real economic damage in the process.

Conclusion

President Obama's call for expanding benefits, while unspecific, could open the door for broad expansions that are not only counterproductive for Social Security's finances but would crowd out other important priorities. With the Social Security program already underfunded, substantially adding to the shortfall by increasing benefits for all seniors regardless of income would be unwise. It would be far more responsible to focus on Social Security reforms that make the system solvent while providing targeted enhancements to those most in need.