Repatriation Tax Holiday Doesn't Work As a Highway Trust Fund Offset

With the Highway Trust Fund (HTF) running low and the threat of disrupting highway construction later this summer, lawmakers are scrambling to come up with a short-term solution to add more money to the fund. However, a new Joint Committee on Taxation analysis shows that one popular idea to "pay" for the transfer – a tax holiday for corporations returning cash held overseas, or "repatriation tax holiday" – actually adds to the debt and therefore cannot be used as an offset.

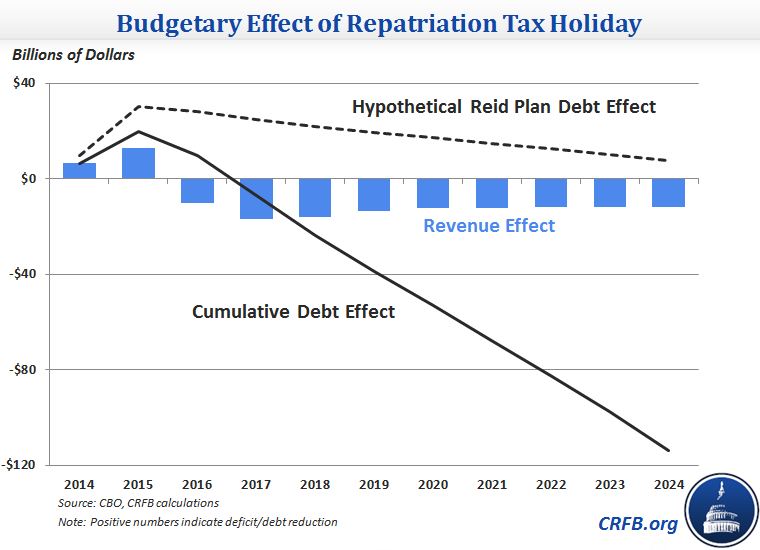

Because of the budget agreement passed last year, any money transferred into the trust fund is required to be offset with revenue elsewhere. The New York Times is reporting that Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) and Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) are working on a proposal to use revenue from a one-time repatriation tax holiday in conjunction with a restriction on counting borrowing costs against repatriated profits to keep the HTF afloat. According to Reid aides, the combined proposal would reduce the debt on net by $3 billion over 10 years despite the $96 billion cost of the repatriation holiday in isolation.

Despite saving $3 billion over 10 years, lawmakers propose transfering the full $30 billion raised in the first two years, ignoring the $27 billion in costs over the following eight years (and the likely future costs beyond then as well). If they could actually produce $30 billion of net revenue, that could stave off the HTF's exhaustion for almost two years. To actually fund the HTF for ten years would require $170 billion.

For background, U.S. multinational companies can defer taxes on non-financial income earned overseas until they bring the money back to the United States. When they bring it back, the income is subject to a 35 percent corporate rate, although the companies get a credit for taxes paid to foreign governments. Companies have lots of cash "trapped" this way: estimates suggest that American companies have between $1.7 and $2 trillion of cash overseas. In 2004, lawmakers enacted a one-year "repatriation holiday" that allowed businesses to repatriate income at a 5.25 percent tax rate, instead of 35 percent. The IRS found that companies repatriated $362 billion during the holiday.

Based on data from the last repatriation, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that bringing back the 2004 holiday for 2014 would raise $20 billion in 2014 and 2015 but would cost $115 billion over the next eight years, for a total cost of $96 billion. The score reflects a number of different factors:

- Companies will repatriate much more income during the holiday. However, some of this income would have been repatriated anyway.

- By moving up repatriations, companies will then repatriate less income in future years.

- Perhaps most importantly, companies may delay repatriation in future years and/or earn more of their income overseas in anticipation of another repatriation holiday, reducing the corporate tax base.

Obviously, counting the first two years of repatriation holiday revenue, even with the limit on corporate interest deductibility, to pay for a transfer to the HTF would be short-sighted given that significant costs would follow. Reducing corporate tax revenue in the future to fund the HTF for a short period of time is not fiscally sound.

Importantly, this proposal is quite different from what House Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) did in the Tax Reform Act. Camp did not allow companies to choose repatriation; the proposal taxed all unrepatriated income at a reduced rate as a transition to a territorial tax system where companies would no longer pay any U.S. tax on their overseas business income. That provision raised $170 billion over ten years, and most of that revenue was dedicated to the Highway Trust Fund. Granted, the proposal did double-count the tax revenue for both the HTF and for making the plan revenue-neutral. However, it at least raised enough revenue to make the fund solvent through 2021.

With only a few months left before the Highway Trust Fund's low balances disrupt ongoing construction projects, lawmakers will likely need to rely on a general revenue transfer, at least in the short term. Nonetheless, they will be required to offset the transfer with real savings and should be working in the interim to develop a long-term solution.