No, the New Simpson-Bowles Plan Does Not Call for More Austerity Than the Old One

We have already responded twice to a wrong-headed call from the Center for American Progress to abandon pursuit of a debt bargain in favor of replacing only 40 percent of the sequester. The paper rightly points out that substantial progress had been made on bringing down debt levels, and that a falling debt-to-GDP ratio for the next few years reduces the immediacy of the debt threat. Yet just because the situation looks better over the next few years does not mean we are out of the woods. And CAP’s suggestion that more deficit reduction will lead to growth-stunting short-term austerity has it backwards – a long-term deficit reduction plan is probably the best way out of austerity.

Take for example the Bipartisan Path Forward (BPF), the new plan released by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson. That plan reverses most of the sequester, and includes only about $50 billion of deficit reduction in 2013 and 2014 compared to $130 billion for the sequester (even as it reduces the deficit by twice as much over ten years). The BPF gets 95 percent of its deficit reduction in 2016 and beyond.

Yet Linden suggests that this new plan has more austerity than the Fiscal Commission plan, co-chaired by Simpson and Bowles. Linden states:

Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles, for example, recently released a new version of their plan for deficit reduction. With the unemployment rate so much higher and growth so much slower than they expected when they wrote their original plan, does their new plan call for a somewhat higher level of spending for 2014 than they proposed originally? It does not. In fact, the new plan from Simpson and Bowles actually envisions total 2014 federal spending about $170 billion below the spending level in their original plan.

Though this fact is technically right, it includes substantial omission that leads to a false conclusion. In fact, economic policy in 2014 under the Bipartisan Path Forward will be far more expansionary than what was projected under the Fiscal Commission plan.

How can this be true? For starters, the paper measures in nominal dollars rather than as a percent of GDP. Spending as a percent of GDP is indeed higher in 2014 under the Bipartisan Path Forward than the Fiscal Commission. Deficits as a share of GDP are much higher. More fundamentally, while the CAP paper rightly identifies the $170 billion different in total spending, it fails to identify the source of that difference (which is non-contractionary), it looks at only one side of the budget, and it ignores the impact of monetary policy. It also ignores the baseline context: what the budget would look like in the absence of further action. The current fiscal environment is already one of austerity in the form of the sequester -- a policy that was absent in December 2010 -- and the BPF largely reverses that policy.

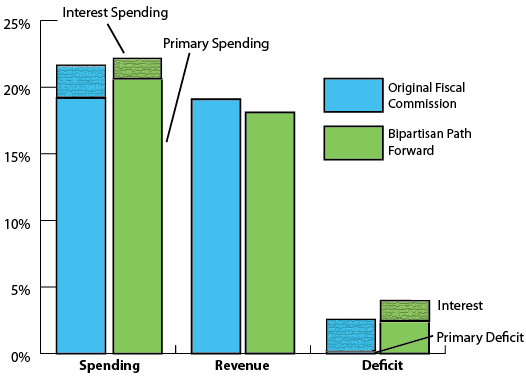

FY 2014 Budget Metrics in Original Fiscal Commission Plan and Bipartisan Path Forward (Percent of GDP)

Source: Fiscal Commission, Moment of Truth Project

The lower spending level CAP identifies is more than entirely accounted for by one thing: lower interest spending. While total federal spending is $162 billion lower in the Bipartisan Path Forward than the Fiscal Commission plan, interest spending in 2014 is $185 billion lower. This means that even with downward adjustments to health care spending estimates and discretionary spending cuts since December 2010, primary spending in the Bipartisan Path Forward is still $23 billion higher than in the Fiscal Commission (or 1.4 percent of GDP higher). This means the source of the supposed austerity is coming from fewer payments to bondholders, half of whom live abroad and many of whom are either wealthy individuals or long-term pension funds, who are unlikely to spend much of the resulting income in a way which would boost aggregate demand. This is especially true given that more than the entire reduction in interest payments come from lower interest rates, which we will later explain are themselves expansionary.

In addition, revenue collection is more than $300 billion lower in 2014, which means more money in the hands of the consumers. A portion of this, about $50 billion, is the result of policy differences between the Bipartisan Path Forward and Fiscal Commission. The rest is mainly technical and economic baseline differences. When accounting for both sides of the ledger, the Fiscal Commission plan had total 2014 deficits $206 billion lower than Bipartisan Path Forward and primary deficits $391 billion lower.

Finally, there is the matter of interest rates. Back in August of 2010, CBO projected the three-month interest rate (which is closely aligned with the federal funds rate) at 4.1 percent. Now it projects that rate at 0.1 percent. Yes, this means lower interest payments from the government. But more importantly, lower interest rates are a form of expansionary economic policy which encourage individuals and businesses to spend more for consumption and investment. According to one very rough rule of thumb, a 1 percent reduction in short-term interest rates leads to a 0.4 percent expansion in GDP.

|

ROUGH Economic Impact of Differences (billions)

|

||||

|

|

Original Fiscal Commission

|

Bipartisan Path Forward

|

Difference

|

ROUGH Economic Impact |

|

Primary Spending

|

$3,413

|

$3,436

|

+$23

|

+$25

|

|

Revenue

|

$3,387

|

$3,019

|

-$368

|

+$180 |

|

Short-Term Interest Rate*

|

4.1%

|

0.1%

|

4.0%

|

+$265

|

|

Total

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

$470 |

Source: Fiscal Commission, MOT, author calculations

*Denotes CBO's projection of three-month T-bill rate in FY 2014

Note: Assumes a multiplier of 1 for primary spending increases, a multiplier of 0.5 for revenue decreases, and a 0.4 percent increase in GDP for each 1 percent decrease in the short-term interest rate.

Add everything together using some very rough multipliers and rules of thumb, and one could conclude that the new Bipartisan Path Forward in conjunction with other economic policy creates $470 billion (2.8 percent of GDP) more economic activity in 2014 than the original Simpson-Bowles and the late 2010 policy environment did. This is hardly consistent with the claims made by CAP.

Of course, these numbers should be taken with an incredible amount of caution. And as CAP rightly points out, different situations merit different economic responses. In addition, new projections aren’t all rosy. While higher short-term deficits may be better for the immediate economy, they also lead to larger debt levels which could threaten the medium and long-term.

Debt in 2014 under the Bipartisan Path Forward is 78 percent of GDP, compared to 70 percent under the Fiscal Commission plan. If not brought under control, these debt levels could begin to stunt investment, result in a loss of confidence, and leave the country less equipped to deal with future economic or other national crises.

In the end, the best thing we can do for economic growth is replace the abrupt and temporary sequestration cuts with a deficits reduction package that is larger, more gradual, more permanent, more intelligent, and more focused on reforming our tax and spending programs to promote short as well as longer-term economic growth. Simpson and Bowles explained how this would work in their report:

The argument that we should not enact comprehensive deficit reduction until the economy is stronger presents a false choice. Enacting a deficit reduction plan today is not the same thing as implementing immediate austerity. One of the guiding principles of the Fiscal Commission and this plan is that deficit reduction should be phased in gradually to avoid harming the economic recovery. Indeed, one of the reasons to act now in putting a plan in place is to allow time for the changes to be phased in gradually.

Designed properly, a comprehensive deficit reduction framework can promote short- and long-term economic growth by not only avoiding the effects of the sequestration but reducing uncertainty, improving confidence in future economic growth, promoting work, savings, and investment over the long-term, and reducing the likelihood of future debt crises.

On the other hand, continuing to wait to enact a comprehensive deficit reduction plan carries with it no true benefits and substantial economic risk.