Loren Adler: Tax Extenders Deal Could Undermine the ACA

Loren Adler, Research Director for the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, wrote a guest post that appeared on the RealClearPolicy blog. It is reposted here.

It's sadly no surprise that lawmakers are working on an irresponsible package of tax cuts without any pretense of caring about the massive $700 billion cost, but hidden in that negotiation is an attempt to undermine the Affordable Care Act's cost-control efforts and deal a huge blow to workers' pocketbooks.

The deal reportedly includes a two-year delay of the excise tax on high-cost, employer-provided insurance plans — commonly referred to as the "Cadillac tax" — along with a similar delay of the medical-device tax, in exchange for fully funding the ACA's "risk corridor" program (which limits insurers' losses if their costs to cover enrollees end up significantly exceeding the premiums charged, and vice versa). On top of that, last week, the Senate voted 90-10 to fully repeal the Cadillac tax.

Ironically, this news comes not long after the Congressional Budget Office detailed just how costly ACA repeal would be, adding $5 trillion to the debt over the next 20 years, and amid growing evidence that the ACA is playing a role in the current health-care spending slowdown. Controlling health-care costs, as the ACA sought to achieve, will prove critical to our ability to afford other priorities like a strong social safety net and important investments.

Delaying the Cadillac tax — the law's primary means of addressing private-market health spending — lends credence to critics' arguments that many of the ACA's cost controls are unrealistic and will be undone before any debt reduction can be achieved.

The Importance of the Cadillac Tax

The two-year delay itself may not be prohibitively expensive, but it surely makes full repeal far more likely, which would blow a big hole in the budget. Constituencies fearful of the Cadillac tax already won a delay to its current 2018 start date during the bill's negotiations. Any further delay would signify resignation to eventual full repeal.

The excise tax indirectly chips away at the nation's largest tax expenditure — the exclusion of employer-paid health insurance premiums from any taxation — which is a regressive tax break that will cost $329 billion in foregone revenue in 2015 and nearly $4.4 trillion over 10 years, according to the Treasury Department.

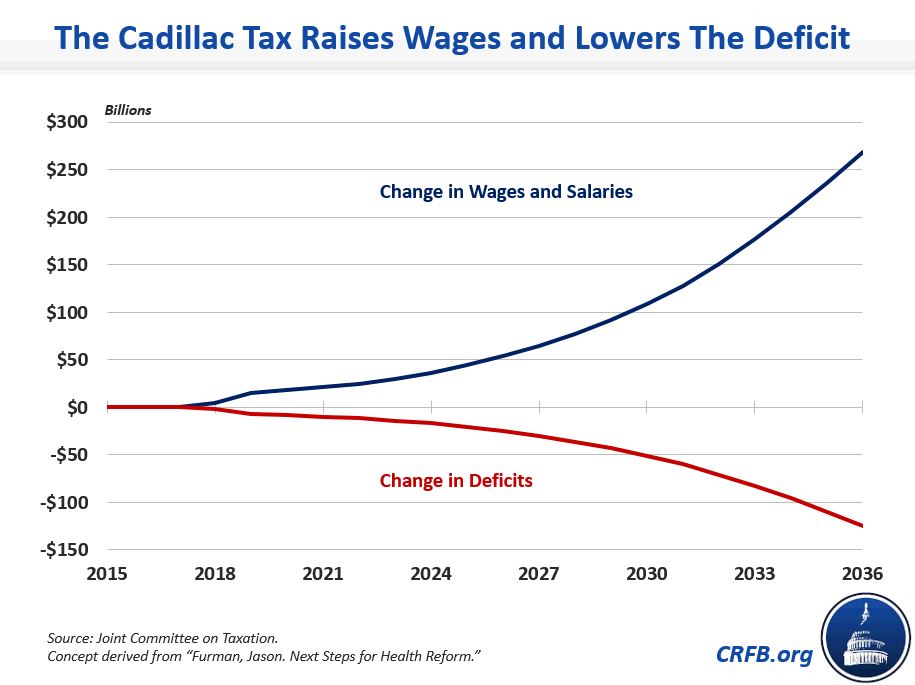

In doing so, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates, the Cadillac tax will raise $91 billion through 2025, and more importantly will generate roughly $600 billion of revenue in the subsequent decade. That makes the tax one of the ACA's most important levers to reduce long-term deficits.

It is also the key lever for addressing rising costs in the employer market, where most Americans get their health insurance.

The existing tax exclusion for employer-provided health benefits, an accident of history, distorts the health-insurance market by incentivizing companies to spend less money on employee wages and more on health benefits, thereby driving up health-care costs and suppressing wages. This distortion has led many employers to offer lavish, often unnecessary health benefits because such benefits are untaxed, which in turn increases the demand and therefore prices for health-care services throughout the system.

By indirectly limiting this tax break, the neutral Congressional Research Service estimates, the Cadillac tax will reduce private insurance costs by roughly 3 percent in 2024, and by a growing amount over time. Importantly, the tax already seems to be having clear effects on the design of employer-provided health plans and has shown itself to be an important tool for slowing private health-spending growth (and may even be playing a role in the recent slowdown). Even delaying the excise tax, then, could halt investments being made and help reverse current progress on controlling health-care spending.

Further, a wide body of evidence suggests that employers care about total employee compensation, and thus reduce wages when health benefits are more expensive and vice versa. In fact, the rapidly rising cost of employer-provided health insurance has almost certainly contributed to the slow growth of real wages over the last few decades, particularly among the middle class, for whom health benefits make up a relatively high proportion of their compensation.

The Cadillac tax helps combat this problem by encouraging employers to offer less costly health plans and instead increase wages. In fact, CBO and JCT estimate that the excise tax, if left in place, will lift workers' wages by $45 billion per year by 2025,an effect that will grow exponentially. For comparison, as the administration's Jason Furman noted recently, this boost is twice the size of the wage gain that would accrue to workers if the minimum wage were increased from $7.25 to $10.10 per hour.

And while many employers will certainly offer higher wages and shift to a plan that requires higher out-of-pocket costs (deductibles, copays, etc.), to the degree that employers are able to reduce their health costs through greater efficiency (which should not be too difficult given the plethora of waste in our health-care system) or narrower but still sufficient networks, workers could end up with higher wages without facing higher out-of-pocket health-care expenses.

Harbinger of a Costly Capitulation?

Beginning to unwind the ACA's key cost controls, like the Cadillac tax, is a slippery slope to start walking. Many of the law's important cost-saving reforms also have powerful interests lined up against them, from Medicare Advantage plans to hospitals to post-acute-care facilities, which will all be emboldened by a blow like this. Similarly, the Cadillac tax is not the only proposal that has been criticized as politically unrealistic or that relies on indexing thresholds slower than their expected rate in order to save more money over time.

Specifically, the ACA reduced payment updates for hospitals in Medicare by roughly one percentage point annually in perpetuity to adjust for productivity growth. This may eventually become untenable as a matter of policy — if, in fact, hospital productivity cannot be improved that much, as former CMS Chief Actuary Richard Foster and others have argued — but it will almost certainly first become difficult to sustain politically.

The tax credits to help individuals afford their marketplace insurance premiums, central to the law, are (approximately) restricted from growing faster than per capita GDP, which will cause them to slowly erode over time as long as health-care premiums continue to outpace GDP growth, as has nearly always been the case historically. Simultaneously, because eligibility for subsidies is tied to percentages of the federal poverty line (FPL), which grows annually only with inflation —slower than wages) — a smaller percentage of the working-age population will be eligible for subsidies over time.

Add to all of this serious efforts to repeal the ACA's reduction to overpayments for Medicare Advantage plans and the Independent Payment Advisory Board, among other provisions, and you can see the path to trillions of dollars in savings disappearing, as critics have warned.

Moreover, it's not just the threat that these provisions might eventually be repealed without offsets. Pumping the brakes on bending the health-care cost curve now could cause many actors throughout the health system to second-guess their investments in new models of care delivery and stall future improvements, undermining health reform. In fact, there's evidence that such efforts in anticipation of continued focus on reducing costs may already be having an impact.

Instead of pulling back on cost-containment efforts, therefore, we need to double down on those that are successful like the Cadillac tax.

What Does This Mean?

At best, this deal would spell only a minor hiccup to the ACA's (so far promising) cost-control efforts. One positive sign is that lawmakers at least appear unwilling to opt for full repeal, instead pursuing a delay, despite the fact that the rest of the package shows zero concern for its fiscal impact.

At worst, this agreement could foreshadow myriad efforts to undo many of the laudable cost-control efforts in the ACA. And while much has (rightfully) been made of the impressive health-care spending slowdown underway, national health expenditures are still expected to eat up a larger and larger share of our economy over time, reaching nearly 20 percent of GDP within ten years (up from 17.5 percent last year), and federal health-care spending as a percentage of GDP is projected to jump 50 percent by 2040.

As the public trustees for Social Security and Medicare noted recently, we "will need all of current law's cost containment and more to ensure that [Medicare] remains on a financially secure footing."

Further, unwinding the ACA's cost controls undermines the case for future expansions to the law, such as fixing the "family glitch" or increasing cost-sharing assistance, or for any expansions to the social safety net. If the public and policymakers come to believe that pay-fors will eventually be reversed, such efforts will become far more difficult to achieve.

"My Views" are works published by members or staff of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, but they do not necessarily reflect the views of all members of the committee.