ACA Repeal Could Add $5 Trillion to the Debt Within 20 Years

Much of the focus on the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO) score for repealing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) naturally has focused on the ten-year budgetary and economic feedback effects, which showed that repeal would increase deficits by $353 billion on a static basis, or by $137 billion if macroeconomic effects were incorporated. As we pointed out in our write-up, though, CBO also provides an estimate of the second-decade effects, finding that repeal would increase deficits over the second decade in the broad range of one percent of GDP (which implies around a $3.5 trillion deficit increase).

CBO doesn't provide a detailed year-by-year score beyond the first ten years because those estimates, as it explains, "would not be meaningful because the uncertainties involved are simply too great." However, the report does provide enough information for a reasonable estimate to be made based on the growth rates of the broad categories of policies, which show the savings generally rising much faster than the costs.

To estimate the long-term impact of the legislation, CBO divides the bill into parts and assigns simplifying growth rates to each part. Specifically, CBO assumes the following:

- Savings from repealing coverage provisions – including new spending as well as revenue from the mandates and Cadillac tax – will grow by about 2 percent per year

- Costs of repealing Medicare and Medicaid savings – including reduced growth rates for provider payments -- will grow by about 15 percent per year

- Costs of repealing non-coverage tax increases – the biggest being the Medicare investment income tax – will grow by about 6 percent per year

These differing growth rates are due to features in the Affordable Care Act law whereby – assuming policymakers stick to the law – changes in the underlying growth rate of Medicare lead to faster growing savings in that program, while the combination of a failsafe designed to limit the growth of exchange subsidies and rapidly increasing revenue from the Cadillac tax lead the net costs of coverage to grow more slowly.

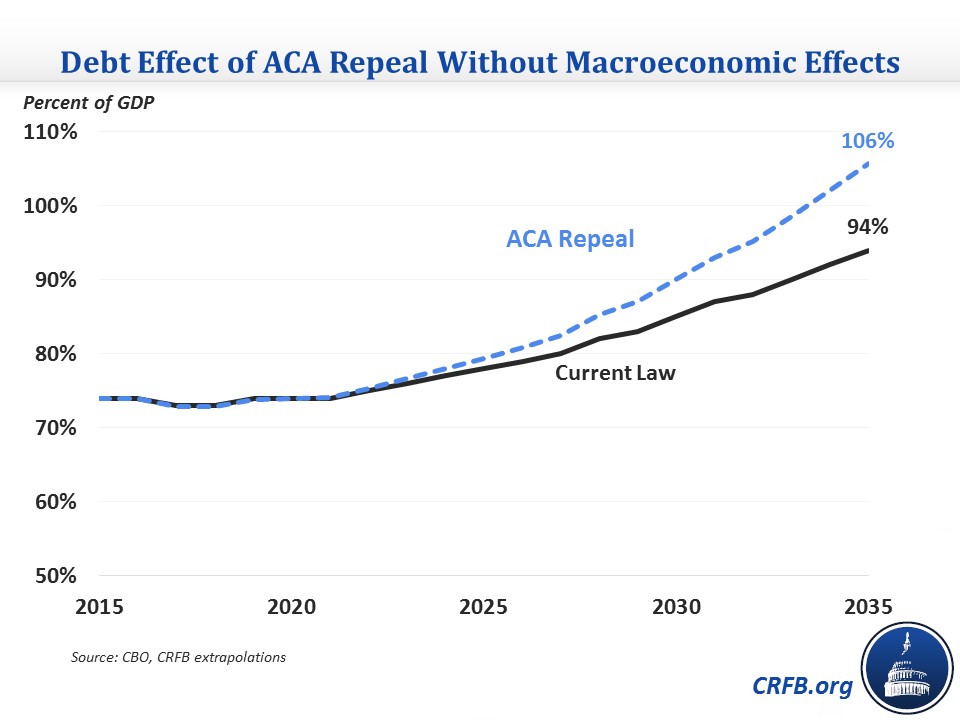

Therefore, because the Medicare savings and revenue in the Affordable Care Act grow so much more quickly than the net costs, the relatively small cost of repeal in the first few years is expected to grow rapidly over time. Roughly, based on CBO’s numbers, repealing the ACA (before incorporating dynamic effects) would cost $3.5 trillion increase in the second decade. Including interest costs associated with those higher deficits, though, repeal could add about $5 trillion to the debt by 2035, which translates into a roughly 12 percent of GDP debt increase.

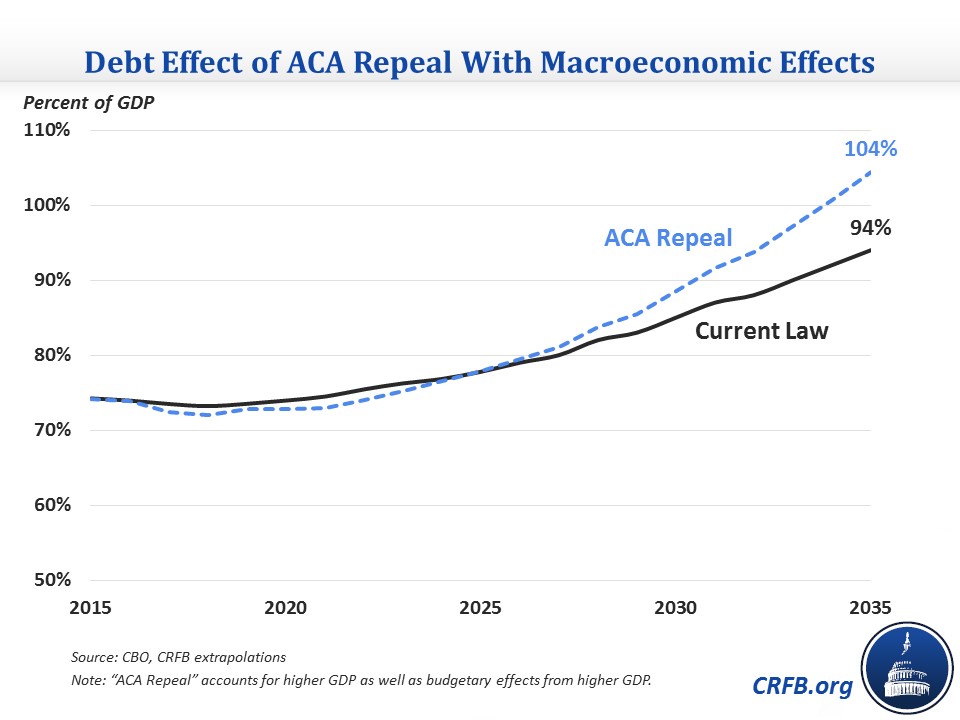

Incorporating the positive economic impacts of repealing the ACA, debt to GDP would still grow substantially over time. Due to the combination of lower net costs and higher GDP, repeal would leave 2025 debt at its current law level of 78 percent of GDP. Beyond that, though, based on our rough estimates, repeal would still add nearly $4.5 trillion to the debt by 2035 and would increase debt-to-GDP by 10 percentage points, almost as much as the static estimate.*

Of course, CBO's caveat about the uncertainty of longer-term estimates still applies, and the uncertainties pull in both directions. On the one hand, there is some question about the long-term sustainability of the ACA's Medicare payment cuts and growth restraint of the exchange subsidies, although legislation rolling these restraints back would traditionally have to be offset under pay-as-you-go rules. But on the other hand, to the extent that the ACA has contributed to the recent health care slowdown by catalyzing delivery system reforms and other changes within the health care system, repeal could cost significantly more if it slows progress or rolls back efforts in these areas (CBO does not assume any broad increase in health care cost growth from repeal). An uncertainty that could go either way is whether each budget category's long-term growth rate, which reflects its growth towards the end of the ten-year window, accurately depicts what would happen in reality.

Although there is considerable uncertainty around the estimate, CBO finds that full ACA repeal would increase deficits by growing amounts over time. Certainly, if Congress plans on adding $5 trillion to the debt over the next two decades, they should at least find a way to pay for the cost of doing so.

*CBO does not provide specific estimates of the increase in GDP from repeal after 2025 but states that the dynamic effects, which already decline between 2019 and 2025, would decline further over the ten-year window. For the purpose of our estimate, we assumed the GDP increase would decline linearly from 0.6 percent in 2025 to about zero by 2035. Regardless, the dynamic effect is small relative to the static budgetary effects, so a different rate of decline in the GDP increase from repeal would likely have little effect on the debt-to-GDP numbers.