Government Spending Just Keeps on Growing

The latest Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline shows that federal spending this year will be the largest it’s ever been outside a crisis – far exceeding pre-pandemic levels. According to CBO’s latest projections:

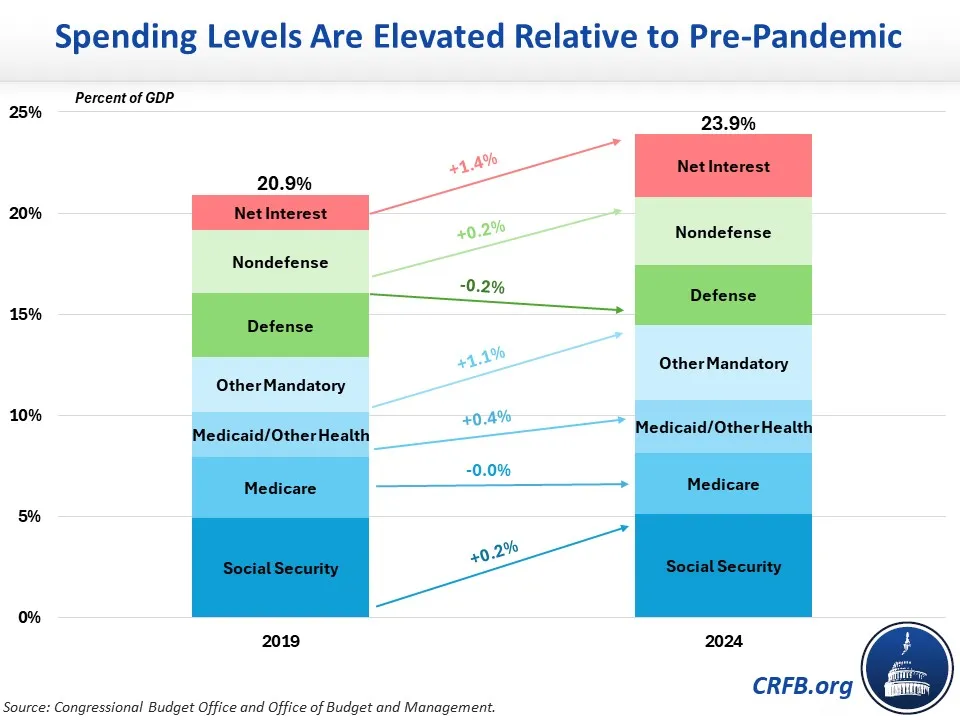

- Spending has grown from 20.9 percent of GDP in FY 2019 to an estimated 23.9 percent of GDP in 2024.

- Most of this recorded spending growth is due to the rising cost of interest payments on the national debt and non-health, non-Social Security mandatory spending.

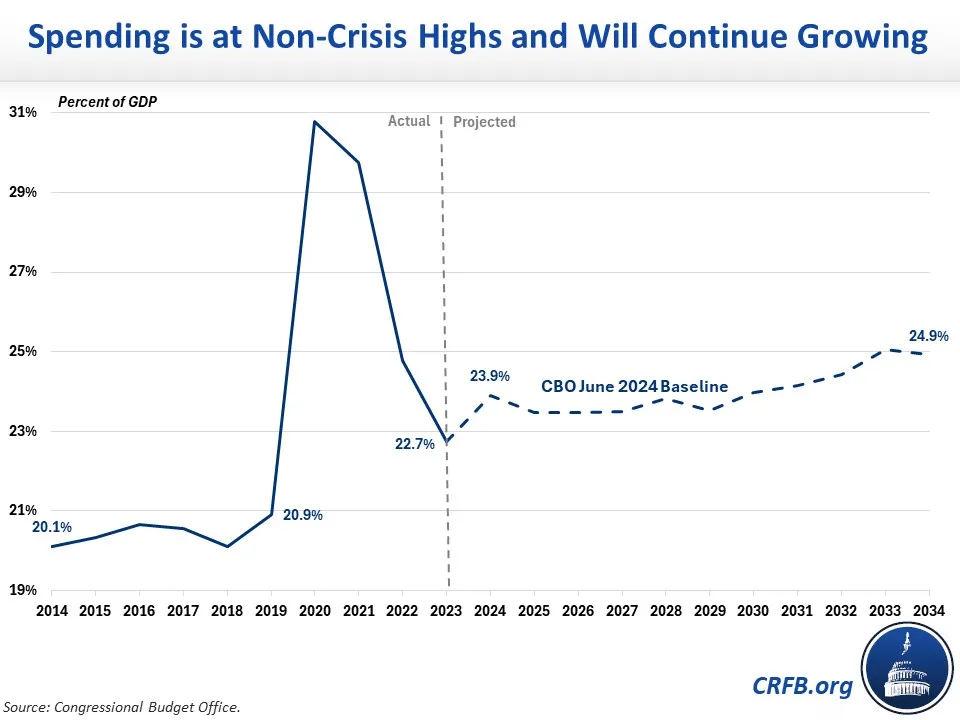

- Spending is projected to remain relatively flat through 2029 before growing to 24.9 percent of GDP by 2034.

- Social Security, health care, and interest costs are each projected to rise by about 1 percent of GDP through 2034, while other spending is projected to fall by 2 percent of GDP.

- Spending will total 24.1 percent of GDP over the next decade – significantly higher than the 21.0 percent of GDP average over the last 50 years.

Spending this year is estimated to total 23.9 percent of GDP, which is 14 percent and 3.0 percentage points of GDP higher than it was in 2019. It is also 2.4 percent of GDP higher than projected in CBO’s January 2020 baseline, suggesting this increase was largely unanticipated.

Nearly half of the increase in spending from FY 2019 to 2024 – 1.4 percent of GDP – is due to increased interest payments on federal debt, which is a product of both the large buildup in federal debt and the significant rise in interest rates. Debt itself has grown from 79 to 99 percent of GDP over this time, while the 3-month Treasury yield has increased from 2.2 to 5.2 percent and the 10-year yield from 2.5 to 4.5 percent.

The bulk of the remaining spending increase – 1.1 percent of GDP – comes from non-health and non-Social Security “other mandatory” spending, which totaled 2.7 percent of GDP in 2019, peaked at 10.5 percent of GDP in 2021 as a result of pandemic-related spending, and is now projected to reach 3.7 percent in 2024.

A small portion of the increase between 2019 and 2024 is due to lingering COVID relief – mainly the Education Stabilization Fund. But most is the result of higher spending on student loans (especially due to recent executive actions), spending for deposit insurance under the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) following last year’s troubles in the banking sector, and increased spending on veterans and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (partially due to legislation and executive actions).

In addition to the growth in other mandatory spending, Medicaid and other health spending has grown by about 0.4 percent of GDP while Social Security and nondefense discretionary spending have each grown by about 0.2 percent of GDP. Defense discretionary spending has shrunk by about 0.2 percent of GDP, while Medicare spending has remained roughly flat.

This recent spending growth is well above trend. From 2014 to 2019, spending hovered in the range of 20 to 21 percent of GDP. Spending then surged during the pandemic to a peak of 30.8 percent of GDP in 2020, falling to 22.7 percent by 2023, and then rising to a projected 23.9 percent of GDP in 2024.

Looking forward, spending is projected to fall modestly next year and remain relatively stable through 2029, as discretionary and other mandatory spending fall as a percent of GDP. But beyond 2029, the rising costs of Social Security, Medicare, and interest payments are projected to overtake this downward pressure, boosting spending to 24.9 percent of GDP by 2034.

Over the next decade, spending is projected to total 24.1 percent of GDP – well above the 50-year historic average of 21.0 percent of GDP and higher than any time in history outside of a war, recession, or other crisis.

This high and rising spending – in combination with flat revenue collection, which is roughly around its 50-year average of 17.3 percent of GDP in 2024 but will stabilize around 18.0 percent for most of the budget window – is driving high deficits and a rising national debt. However, debt would grow even higher if lawmakers extend expiring tax provisions without offsetting those changes, resulting in even lower revenue. Policymakers should act soon to reduce the gap between spending and revenue, tackling the drivers of our national debt in order to put it on a sustainable downward path.