The Good News on Social Security: We Have More Time to Improve Disability Insurance

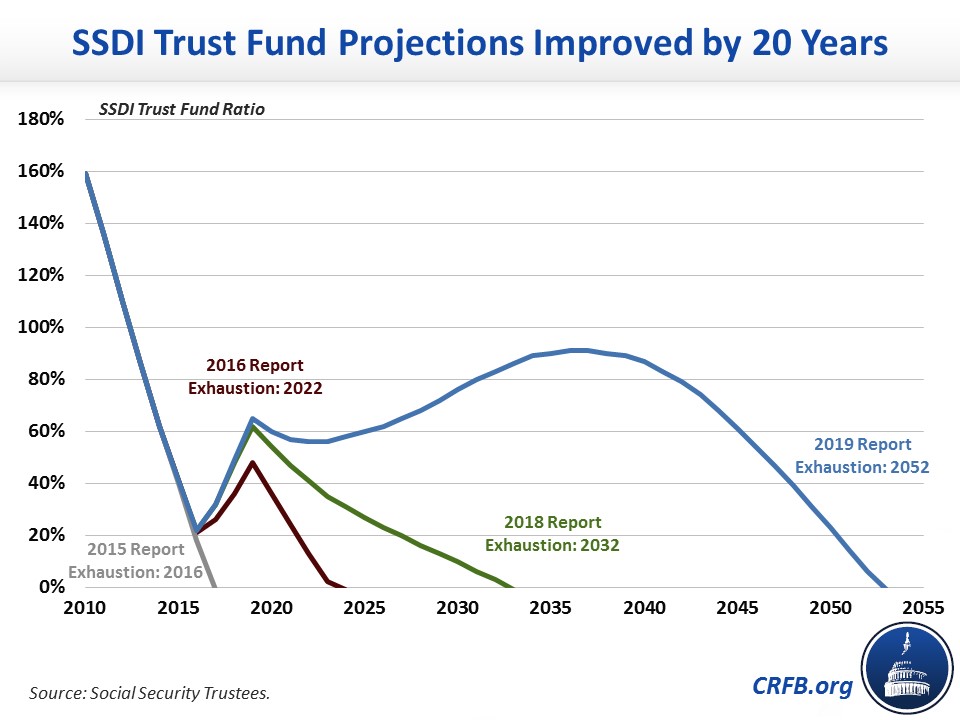

This week's Social Security Trustees' report warned that the program is on a path toward insolvency, with the theoretically combined trust fund set to deplete its reserves in just 16 years. However, there was one bright spot in an otherwise gloomy report: the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) trust fund is now projected to be able to pay full benefits through 2052 – two decades later than projected last year, nearly three decades later than in their 2016 projections, and a two-thirds improvement since 2015. There is still work to be done to secure and address SSDI's finances and improve disability policies, but the situation is much improved from a few years ago.

Not too long ago, SSDI faced significant financial trouble. Back in 2015, the Trustees projected the fund was just a year from insolvency. This projected depletion was in part the result of lower tax collection through the Great Recession but also due to a rapid increase in beneficiaries.

Between 2000 and 2010, the number of disability benefit awards increased by nearly 70 percent. Successful disability applications reached a record high in 2010, and by 2013 the program's rolls swelled to their largest level ever of nearly 11 million beneficiaries. This increase was likely caused by a mixture of demographic factors (more workers reaching peak disability age), economic factors (fewer job opportunities for workers with disabilities during the Great Recession), policy changes (a rising retirement age pushed more people into SSDI), and program-specific factors (for example, very high approval rates from some Administrative Law Judges in the early 2010s) – some of which were likely to pass and others which estimators believed would persist.

It became clear by that time that improvements should be made to the program and that the 2016 insolvency must be avoided. Those realities helped to prompt the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget to form the McCrery-Pomeroy SSDI Solutions Initiative to identify practical policy changes that would help improve the lives of people with disabilities, the program, and the economy while staving off trust fund exhaustion.

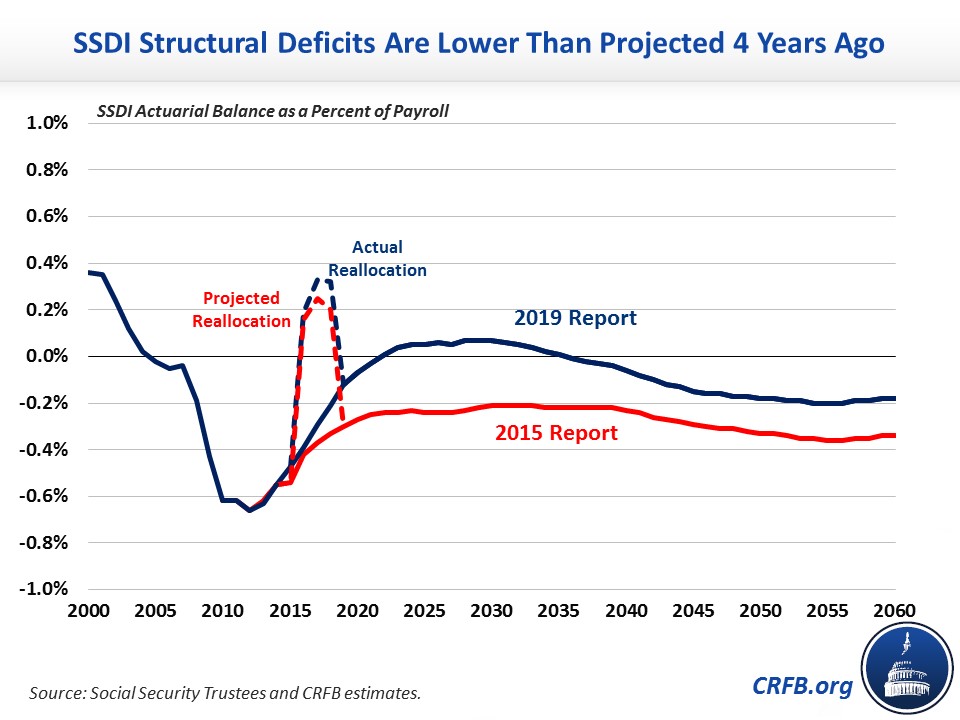

Fortunately, Congress acted in late 2015 to avoid insolvency – largely by temporarily reallocating about $120 billion of payroll tax revenue from the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) program to SSDI but also by making some improvements to the program and extending demonstration authority to try new ways of supporting program beneficiaries. Meanwhile, the Social Security Administration, the Obama Administration, and the Trump Administration acted to make a number of administrative changes to reduce fraud, improve the determination and adjudication process, and test new ways to help people stay at work.

The combination of these efforts and the reallocation was originally projected to push exhaustion to 2022 and reduce SSDI's 75-year shortfall from 0.31 percent of payroll to 0.26 percent of payroll. But at the same time that the reallocation infused new money into the SSDI trust fund, the economy began to strengthen – meaning higher payroll tax revenue and thus more funds going into the program and fewer workers are applying for benefits. In addition, steady reductions in the backlogs of continuing disability reviews has translated into a higher-than-normal worker recovery rate.

The result has been an ongoing improvement in the projected finances of the program. In their 2016 report, the Trustees estimated SSDI would be solvent through 2023 as opposed to 2022. That was pushed back to 2028 two years ago, 2032 last year, and all the way to 2052 this year.

Today, disability applications are even lower than they were before the Great Recession, and rolls have decreased every year since 2014. The strong economy is clearly in part to thank – unemployment is at near-record lows, and the labor market has more jobs than people looking for them, meaning more jobs are available for workers with disabilities. But given just how low applications have fallen, the Trustees believe something more structural is going on. As a result, they revised their estimates of future disability incidence from 5.4 per thousand to 5.2.

Revisions to the Trustees' estimates of disability incidences have reduced their projections of the program's 75-year shortfall by 45 percent since 2015. The reallocation closed another 10 percent. In total, the projected shortfall this year is only about one-third of what it was in 2015.

| SSDI 75-Year Actuarial Balance (Percent of Payroll) | |

|---|---|

| 2015 Projected 75-Year Imbalance | -0.31 |

| Extended Valuation Period | -0.04 |

| Reallocation of Payroll Tax from OASI | +0.03 |

| Legislative and Regulatory Changes | +0.01 |

| Fewer Near-Term SSDI Applicants | +0.09 |

| Lower Projected Long-Term Disability Rates | +0.05 |

| Other Factors | +0.06 |

| 2019 Projected 75-Year Imbalance | -0.12 |

Source: CRFB calculations based on SSA data. Note: numbers may not add due to rounding.

That the SSDI trust fund has 33 years left instead of 13 years or 3 years is great news. But importantly, this improvement isn't a guarantee – and it doesn't mean disability policy can be ignored. If another recession emerges, the number of applicants (or share who are awarded benefits) rises, or projections are simply wrong, costs could rise. A 0.04 percentage point increase in disability rates would effectively reverse the gains estimated in this year's Trustees' report. Moreover, the program continues to face a long-term imbalance, and workers with disabilities continue to face a number of challenges that could be addressed in part with improvements to the program.

Policymakers should continue to push improvements, particularly those that can help workers with disabilities to remain in the workforce. Now that we have evidence the SSDI rolls can be reduced during strong economic times, we can take those lessons to do more to help people with disabilities work during a weaker or more normal economy.

The SSDI Solutions Initiative has put forward 12 sets of recommendations and released four additional papers on ways to improve the program's administration, adopt early intervention methods that prevent disabilities from getting worse, improve the interactions between SSDI and other programs, and ultimately think about structural reforms for how we support people with disabilities as a whole. A number of these proposals have already been adopted or officially proposed, but more should be done. One recent paper, by Jason Fichtner and Jason Seligman, specifically focuses on how best to design pilots and demonstrations projects in order to move many of these ideas forward.

The delay in SSDI's exhaustion is a positive development; it should not be used as an excuse to drag our feet on improving the program for people with disabilities, those who pay into the program, and the economy as a whole.