General Revenue & the Social Security Trust Funds

Social Security is often portrayed in one of two ways, either as its own self-contained program (the “trust fund perspective”) or as part of the broader budget (“the unified budget perspective”). Although focusing on these two lenses is sensible, the reality is more complicated; especially when it comes to the role of general revenue. Even though Social Security is mainly funded by a 12.4 percent payroll tax, general revenue comes into play even under the trust fund perspective. Indeed, since 1965, over $2.5 trillion ($3.1 trillion in today's dollars) of the $20 trillion of income received by the Social Security Trust Funds has come from sources other than the payroll tax, representing 12 percent of the total.

There are three main ways that general revenue has directly or indirectly made its way into the Social Security Trust Funds:

- Direct transfers from the General Fund: The general fund has occasionally reimbursed the Social Security Trust Funds in specific cases to compensate it for policy changes that would otherwise lower its balance. Most recently, Congress passed a payroll tax cut for 2011 and 2012, lowering the payroll tax rate by 2 percentage points to stimulate the economy but authorizing a general fund transfer so the Social Security Trust Funds would be no worse off. The holiday was responsible for $225 billion of transfers. Congress has also used general fund transfers to pay for extra benefit credits to active-duty military between 1957 and 2001, special age-72 benefits for people not covered by the program by 1968, a payroll tax credit in 1984, and other reasons. Overall, nearly $260 billion has been transferred from the General Fund since 1965, or $300 billion in today's dollars.

- Taxation of Benefits: Since 1983, retirees with significant income from sources other than Social Security have paid income tax on a portion of their Social Security benefits (prior to that, benefits were tax-free for everyone). Although this money is paid via the income tax, it is credited back to the Social Security Trust Funds. Since 1983, $370 billion has been transferred from the General Fund due to the taxation of benefits, or $440 billion in today's dollars.

- Interest paid on Social Security bonds: The Social Security Trust Funds currently contain $2.8 trillion of assets, mainly as a result of significant surpluses in the 1990s and 2000s. That money is invested in U.S. Treasury bonds, which earn interest paid from general revenue. The trust funds earned about $100 billion of interest last year and have earned about $1.9 trillion since 1965, or $2.3 trillion in today's dollars.

The first of these three cases represents the clearest case of a general revenue transfer, though only the last case was part of the original Social Security financing system. Importantly, interest paid from general revenue to the trust funds is money the rest of the federal government owes the trust funds. Since 1965, the Social Security system has run a total of nearly $900 billion in net cash surpluses, cash which it has essentially lent to the federal government. Including interest and assuming all else equal (which it may not be), the debt held by the public is $2.8 trillion lower as a result of the money lent by the Social Security Trust Funds.

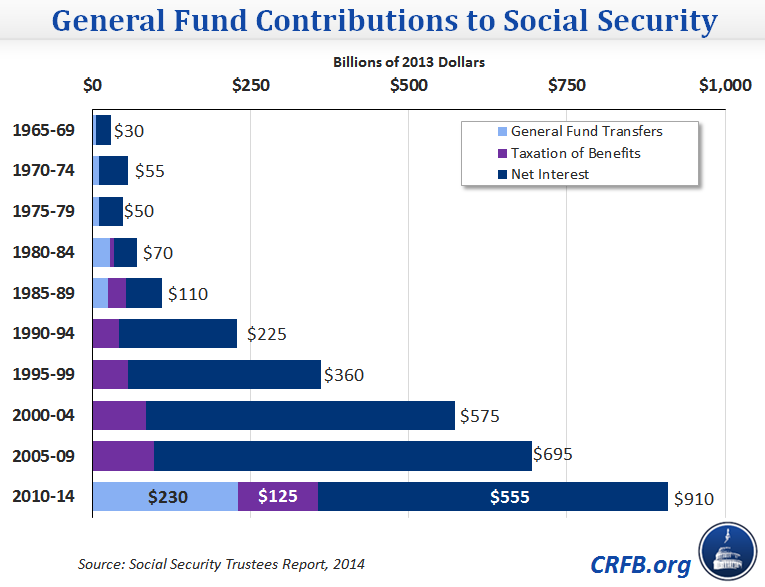

The below chart puts the above numbers in context, showing that the amount of non-payroll tax income contributed to Social Security has increased dramatically in recent years, largely due to interest payments on a large trust fund and the 2011-2012 payroll tax holiday. In today's dollars, nearly 40 percent of all the revenue transfers into Social Security since 1965 have occurred in the past five years.

An additional source of income not counted as general fund contributions above is the amount that the federal government pays on behalf of its 4 million employees, because the government is acting as any other employer would. The government's approximately $250 billion payroll suggests it annually pays about $15 billion in Social Security taxes on behalf of federal employees.

The above calculations look at cumulative annual changes but do not consider interest accumulated on direct general fund transfers and the taxation of benefits. Including interest, the $620 billion of nominal dollars from these two sources has allowed the trust funds to accumulate about $1.2 trillion of assets – roughly two-fifths of their current balance.

Social Security is a largely self-funded program that by law is not allowed to pay out more than it has accumulated in its trust fund. However, the fact that Social Security is financed through its trust funds doesn't mean it operates independently of the rest of the government's budget. Non-payroll tax funds have already played a significant role in the program's financing. Moreover, As Paul Van de Water at CBPP has explained, "when Social Security needs to start cashing in its holdings of Treasury securities to meet its benefit obligations, the federal government [the general fund] will have to increase its borrowing from the public, or raise taxes or spend less" to finance these costs.

In addition, even after the general fund pays back this borrowed money, the Social Security combined trust funds will only remain solvent through 2030 or 2033. It would be wise for Congress to start addressing Social Security's funding shortfall soon, not only to spread out the pressure on the general fund, but also to make Social Security solvent for its own sake and avoid a future 23 percent across-the-board cut in benefits.

If Congress waits until the 2030s to act, the needed changes to keep the program solvent would be significantly larger and more difficult. At that time, the choices to cover the shortfall will be to allow deep and broad-based benefit reductions, steep tax increases, or huge general revenue transfers.