Donald Trump’s Proposal to End Taxes on Overtime

Former President Donald Trump recently proposed eliminating taxes on overtime pay. On a static basis, we estimate ending taxes on all overtime pay would reduce revenue by $1.7 trillion from Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 through 2035, and the revenue loss would grow to roughly $6 trillion in the extreme case that all salaried workers switched to hourly and were able to work overtime (at 150 percent pay) tax-free.

The Trump campaign has said they would incorporate guardrails, which could limit these behavioral effects, but they have not specified the details of those guardrails. We very roughly modelled several possible approaches to limit the tax break by occupation, income, and hours. Under these illustrative scenarios, no taxes on overtime would reduce revenue by $250 billion to $1.4 trillion on a static basis and by $1 to $5 trillion in the extreme case that all workers eligible for the tax cut switched to hourly.

US Budget Watch 2024 is a project of the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget designed to educate the public on the fiscal impact of presidential candidates’ proposals and platforms. Throughout the election, we will issue policy explainers, fact checks, budget scores, and other analyses. We do not support or oppose any candidate for public office.

During remarks in Arizona earlier this month, President Trump stated that he would “end all taxes on overtime.” This would include both income and payroll taxes, based on comments from Republican vice-presidential nominee Senator JD Vance (R-OH).

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) requires employers to pay certain workers “time-and-a-half,” or 150 percent of their base hourly pay, for any work beyond their first 40 hours per week.

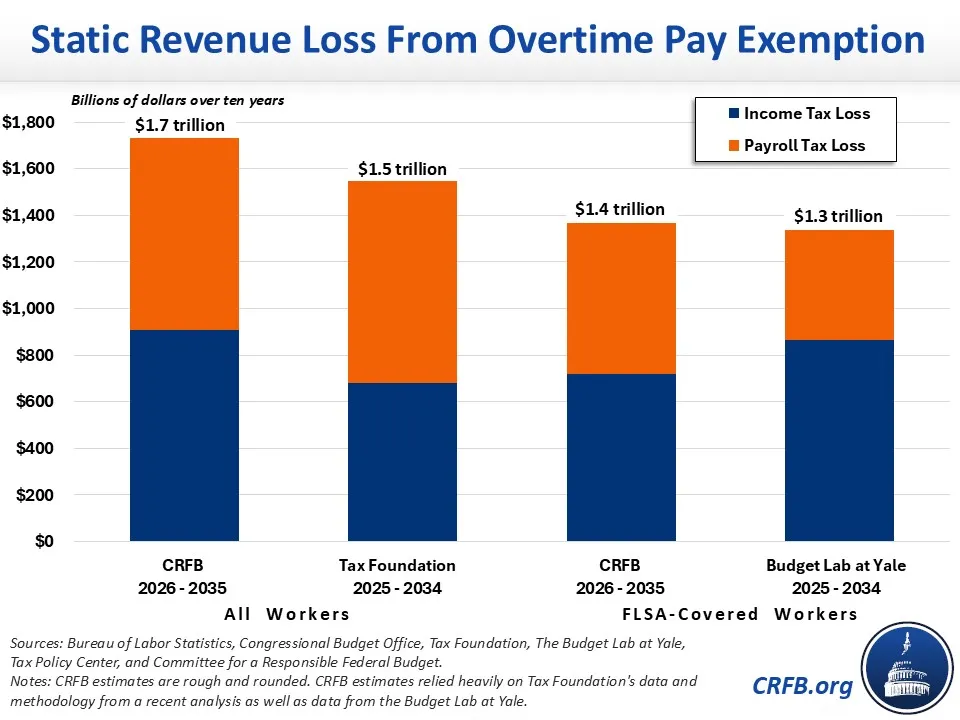

The Budget Lab at Yale has estimated that ending taxes on FLSA-mandated overtime would reduce revenue by $1.34 trillion ($866 billion from income taxes) through 2034 on a static basis. The Tax Foundation, meanwhile, has estimated that ending taxes on all overtime pay would reduce revenue by $1.55 trillion ($680 billon from income taxes) through 2034 on a static basis.

Based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) used by the Tax Foundation, in combination with information from the Budget Lab at Yale, Tax Policy Center’s estimated effective marginal tax rates, and our own assumptions, we estimate eliminating income and payroll taxes on all overtime pay would lose about $1.7 trillion of revenue over the FY 2026 to 2035 period on a static basis, with more than $900 billion of income tax reductions. When limited to FLSA-covered overtime, we estimate the policy would lose about $1.4 trillion over ten years, with over $700 billion from income tax.

Costs would be far higher once behavioral effects were incorporated, as only 7 million of the 34 million workers who regularly work more than 40 hours a week currently receive FLSA-qualified overtime pay on a regular basis.

To understand the potential behavioral changes, we first considered an extreme case that all workers switched to hourly with a time-and-a-half pay model while annual compensation and hours stayed constant. In this extreme case, using a rough method and data developed by the Tax Foundation, we estimate eliminating taxes on all overtime would reduce revenue by about $6 trillion through 2035.1 In other words, no taxes on overtime would likely reduce revenue by between $1.7 and $6 trillion with no guardrails.2

Importantly, the Trump campaign has expressed to us that they would incorporate guardrails to direct the tax break toward hourly and non-exempt salaried workers. Although they did not provide specifics, they suggested guardrails could be developed based on the experience of countries such as France, Austria, and Belgium, as well as the State of Alabama, which have their own tax exemption for overtime pay.

We developed several illustrative examples of guardrails based on occupation, income levels, and hours and have run some very rough estimates of their possible costs. These estimates are meant to convey order of magnitude, and not precise budget scores. Our static and ‘extreme behavioral’ estimates are calculated using different methodologies and therefore are not fully comparable.

Were this tax break limited to occupations currently eligible to overtime under FLSA, we estimate eliminating taxes on overtime would cost $1.4 to $5 trillion. This guardrail would exclude workers that are not covered by the FLSA, such as military personnel, self-employed individuals, clergy and other religious workers, and federal employees. It would also exclude occupations that are exempted from overtime coverage even if paid hourly, including teachers, lawyers, and physicians.

Were the tax break also limited based on income, revenue loss would be significantly smaller. For example, if it were restricted to workers who make less than $150,000 a year – which is roughly the threshold under the Administration's new overtime rule for salaried "highly compensated employees" to qualify for overtime under the FLSA – we estimate it would reduce revenue by $1.3 to $3 trillion.

Rough Estimates of Ten-Year Revenue Loss from Exempting Overtime from Taxes under Different Scenarios

| Static | Extreme Behavioral* | |

|---|---|---|

| No guardrails: All workers eligible for overtime and tax cut | $1.7 trillion | ~$6 trillion |

| Tax cut limited to FLSA-eligible jobs | $1.4 trillion | ~$5 trillion |

| Tax cut limited to FLSA-eligible jobs below $150k | ~$1.3 trillion | ~$3 trillion |

| Tax cut limited to 20 hours per month and FLSA-eligible | ~$500 billion | ~$2 trillion |

| Tax cut limited to 10 hours per month and FLSA-eligible | ~$250 billion | ~$1 trillion |

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Congressional Budget Office, Department of Labor, Tax Foundation, Tax Policy Center, The Budget Lab at Yale, and Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Notes: Figures are rough and rounded and meant to reflect order of magnitude rather than specific budgetary scores. Figures represent total federal revenue loss from income and payroll taxes. The static and extreme behavioral estimates are also calculated using different methodologies, and thus are not fully comparable to each other. Estimates were generated based on data and methods developed by Tax Foundation for a recent analysis as well as data by The Budget Lab at Yale. “FLSA-eligible” means that the employee is covered by FLSA and is eligible under FLSA to receive overtime pay under an hourly pay structure.

* The "Extreme Behavioral" scenario assumes that all workers change to hourly pay with time-and-a-half pay above 40 hours.

The tax exemption for overtime pay could also be capped by hours, as it is in Austria or Belgium. We estimate that if the tax break were limited to the first 20 hours of monthly overtime, it would reduce revenue by $500 billion to $2 trillion. And if it were limited to 10 hours of monthly overtime, it would reduce revenue by $250 billion to $1 trillion.3 However, with such a strict limit it’s not clear the policy could be described as “end[ing] all taxes on overtime.”

Policymakers could also limit the amount of deductible income – for example, France limited the size of their overtime deduction to 7,500 euros for 2023. We have not modelled this option, but it would significantly reduce potential costs.4

In all cases, the wide range reflects the difference between a static estimate and an extreme estimate where all workers switch from salaried to hourly pay.

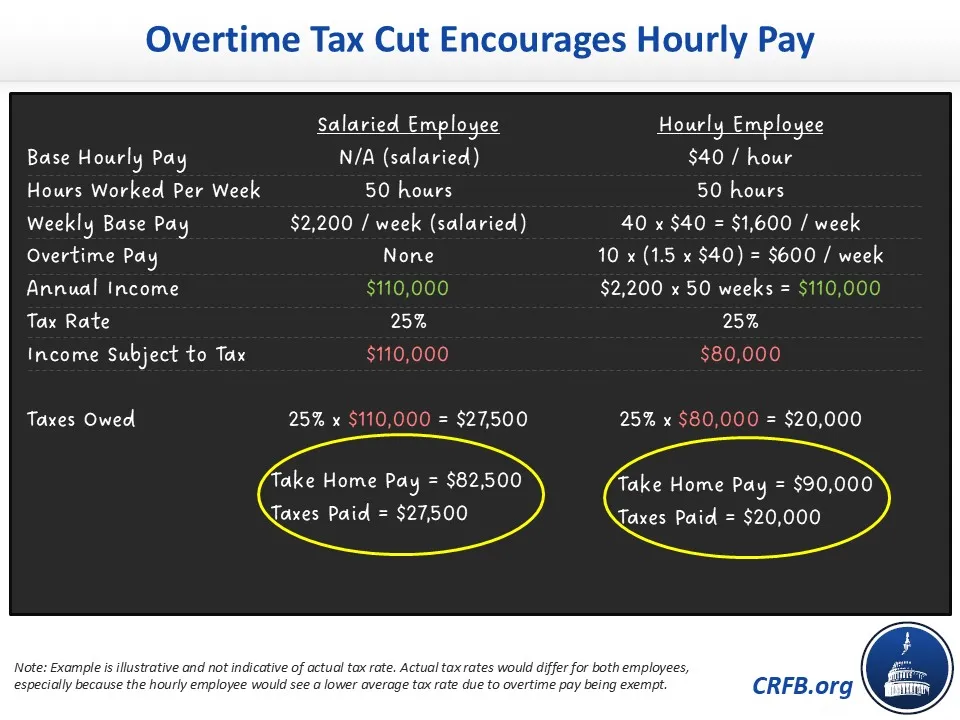

To understand why salaried workers would be enticed to switch to hourly pay, imagine a person making $110,000 a year and working 50 hours per week. With a hypothetical 25 percent flat tax rate, they would owe $27,500 in taxes if paid with an annual salary. But if they were instead paid $40 per hour and $60 per hour for overtime, the person would only pay $20,000 of taxes on the exact same income. Their tax bill would fall by more than a quarter, and meanwhile their employer would also pay less in payroll taxes.5

Importantly, the same incentives that would encourage workers to switch to hourly would also incentivize taxpayers to work more hours, likely boosting economic activity and increasing the size of the economy. However, this increase in output would not translate into much additional revenue, since additional work would generally be non-taxable.6

Overall, it is difficult to estimate the precise fiscal impact of this proposal – particularly without understanding how it might be structured and what guardrails, if any, would be included to limit cost and prevent abuse of this policy.

*****

Throughout the 2024 presidential election cycle, US Budget Watch 2024 will bring information and accountability to the campaign by analyzing candidates’ proposals, fact-checking their claims, and scoring the fiscal cost of their agendas.

By injecting an impartial, fact-based approach into the national conversation, US Budget Watch 2024 will help voters better understand the nuances of the candidates’ policy proposals and what they would mean for the country’s economic and fiscal future.

You can find more US Budget Watch 2024 content here.

1Potential costs could be even higher, since these estimates assume people work the same number of hours every week and don’t engage in legal or illegal gaming to minimize their tax liability. For example, the cost would increase if someone who averages 40 hours per week actually works 45 hours half the weeks and 35 hours the other half. In this scenario, they would accumulate overtime hours, which, under a no-taxes-on-overtime policy, would result in reduced tax liabilities. President Trump’s proposal could incentivize more individuals to structure their working hours strategically to maximize tax savings.

2The Tax Foundation estimated that making all work in excess of 40 hours per week tax free would reduce revenue by $3.1 trillion over a decade on a static basis. Our estimate is substantially higher for several reasons. Most significantly, we assume pay structures are shifted so that all workers are paid “time-and-a-half” after 40 hours, which increases the amount of tax-free income. Second, we assume an effective marginal tax rate of about 37% compared to their assumption which appears closer to 33% (this may reflect our baseline assumption that the TCJA expires as scheduled). Additionally, for several reasons, we estimate somewhat higher existing income for work in excess of 40 hours per week. And finally, we use a budget window from Fiscal Year 2026 to 2035 compared to Tax Foundation’s tax year 2025 to 2034.

3The revenue loss for limiting to 10 hours is more than half of limiting to 20 hours. It appears half as large only due to the significant rounding of our estimates.

4In the illustrative case that all 7 million workers who regularly work overtime were able to deduct $7,500 per year, this policy would reduce revenue by roughly $200 billion over a decade. If with behavioral effects, 34 million workers deducted $7,500 per year, the policy would lose about $1 trillion. Actual revenue loss might be significantly higher since the tax break would go to many workers who sometimes work overtime, or it may be significantly lower since not every worker who regularly works overtime will earn more than $7,500 of overtime pay per year.

5Using actual current law tax rates for 2024, the person’s tax bill would fall from about $24,500 to $15,600, assuming they were single and took the standard deduction. The employer’s payroll tax contribution would fall by an additional $2,300.

6Some revenue feedback could be generated to the extent additional work increased business profits or to the extent no tax on overtime encouraged those working less than 40 hours to work more than 40 hours instead. For example, if a worker increased their weekly hours from 38 to 45, additional tax revenue would be generated on their 39th and 40th hour of work.