Congressional Double-Take on Revenue

The Congressional budget resolution proposes to bring the budget into balance by reducing spending $5.3 trillion over the next decade while keeping revenue at current law levels (i.e., no tax cuts). But at the same time, it calls for roughly $2 trillion worth of tax cuts from repealing taxes in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and extending various expired tax breaks. Some have suggested (subscription required) this $2 trillion difference could be bridged with dynamic growth effects that must now be scored by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). However, we find that even under very generous assumptions, the use of dynamic scoring could only recover about one-third of the lost revenue.

| Source | Direct Revenue Impact | Dynamic Impact (Generous) | Max Percent of Revenue Recovered |

| Repeal ACA Tax & Coverage Provisions | ~$1.3 trillion | ~$0.3 trillion | ~25% |

| Revive Extenders and Enact Tax Reform | ~$0.7 trillion | ~$0.4 trillion | ~55% |

| Total Revenue Lost | ~$2 trillion | ~$0.7 trillion | ~35% |

Source: CRFB calculations based on Senate Budget Committee and Joint Committee on Taxation documents.

The $2 trillion revenue gap in the budget resolutions comes from two sources. First, the budget calls for the repeal of the tax increases enacted in the Affordable Care Act ("Obamacare") to help pay for the expansion of health insurance coverage. We estimate this would cost roughly $1.3 trillion over the next ten years, based on 2012 estimates. The budget resolution also calls for budget process reforms that would allow temporary or expired tax breaks to be continued without offsets, a move that could reduce revenue somewhere in the range of $700 billion, depending on the exact details.

At the same time, the budget calls for repealing the coverage provisions of the Affordable Care Act and enacting tax reform, two changes which could produce additional economic growth and therefore higher revenue collection. Yet this additional revenue – at least as scored by JCT and CBO – will almost certainly fall short of the $2 trillion in revenue losses.

With regards to the Affordable Care Act, it is clear there would be some dynamic gains. Specifically, the ACA is likely to discourage work in a number of ways, including by offering health insurance to those without employment, phasing out insurance subsidies as income grows, increasing employment costs for employers (through the employer mandate), and increasing effective tax rates on workers. The Congressional Budget Office projects these changes to reduce total hours worked by 1.5 to 2 percent (the equivalent of 2 to 2.5 million full-time workers) and reduce aggregate labor compensation by roughly 1 percent.

Repealing the tax and coverage provisions is therefore likely to increase hours worked by 1.5 to 2 percent and increase labor compensation by about 1 percent. Yet according to an analysis from the Senate Budget Committee Republicans, repeal would produce only $300 billion in dynamic offsets – about one-quarter of the total revenue loss from ACA repeal. And even this estimate has been disputed as overly optimistic.

Of course, the ACA repeal is not the only potential source of dynamic revenue gains – the budget resolution also calls for pro-growth tax reform. By lowering tax rates and broadening the tax base, tax reform has the potential to encourage work, investment, and economic growth without adding to the deficit.

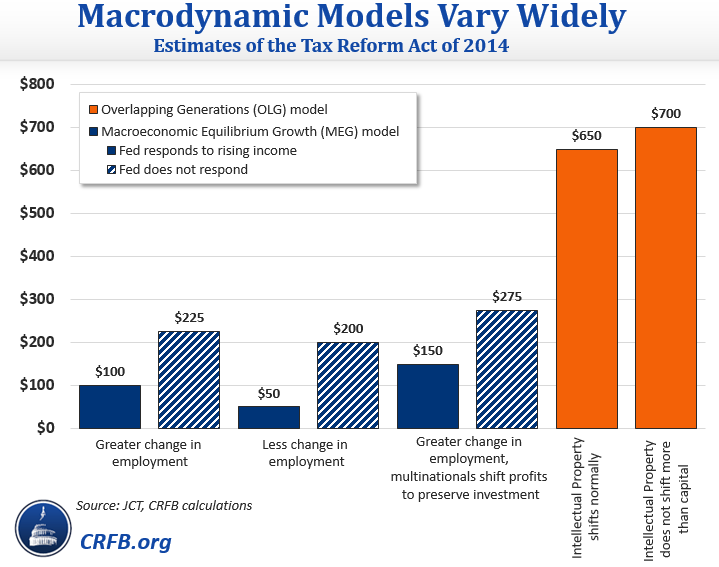

Yet JCT is highly unlikely to find large enough growth effects to pay for the revenue loss unaccounted for in the budget resolution. When former House Ways & Means Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) released the Tax Reform Act of 2014 last year, JCT released a dynamic analysis showing the bill could raise between $50 and $700 billion in revenues from economic growth, and JCT estimates of other revenue-neutral, rate-lowering plans show similar growth effects.

For simplicity, we assume tax reform could generate $400 billion of dynamic revenue – though this number is generous since a weighted average alone would likely be lower and since JCT's higher-end estimates rely on future Congressional action and thus might not be incorporated at all into a point-estimate dynamic score. $400 billion would only cover 55% of the revenue loss from continuing extenders, and 20% of the total $2 trillion loss from also repealing ACA taxes.

The $400 billion estimate is also too generous because lawmakers appear to be focusing on business-only tax reform. Several unofficial estimates performed by JCT economists have shown that such reform would likely produce significantly less growth than a comprehensive bill like the Tax Reform Act.

And although some might argue an additional economic boost from continuing extenders, JCT estimates of permanently extending three of the largest provisions found the growth effects to be minimal and in two cases "so small and uncertain relative to the size of the economy as to be incalculable."

Summing up, a generous prediction of dynamic revenue gains from tax reform and ACA repeal shows that they can indeed produce revenue, but only enough to pay for about one-third of the cost of continuing tax extenders and repealing ACA taxes.

That means that to make the budget a reality, Congress would need to either let a number of extenders expire, retain a portion of the taxes from the ACA, pursue additional pro-growth policy changes, identify at least $1.3 trillion of net revenue, or do some combination of the four.

Dynamic scoring could make some types of pro-growth changes easier to pass, but it can't change the basic math that governments, like people, face trade-offs.