CBO Projects Major Trust Fund Exhaustions on the Horizon

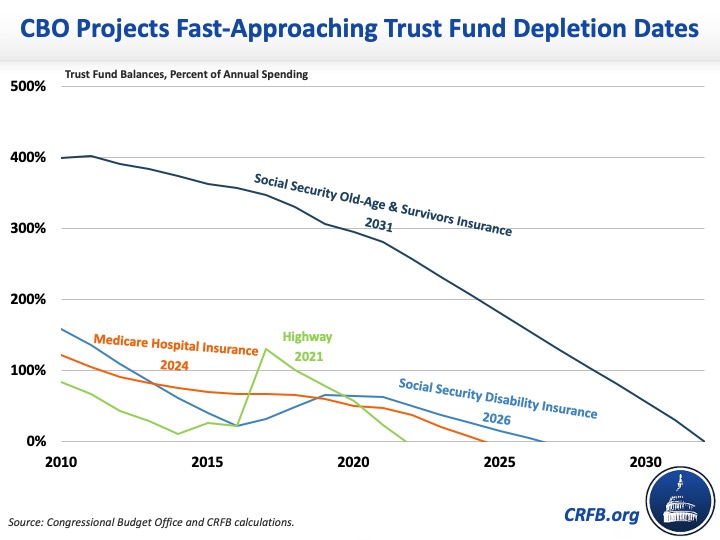

A number of important federal programs — including Social Security and Medicare — are financed through dedicated revenue sources and managed through federal trust funds. According to the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO) latest ten-year budget outlook, four major trust funds will exhaust their reserves within the next 11 years. Specifically, CBO estimates the Highway Trust Fund (HTF) will deplete its reserves in Fiscal Year (FY) 2021, the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund in FY 2024, the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) trust fund in FY 2026, and the Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund in calendar year 2031.

CBO's estimates exactly match projections we released in July of this year.

For all four trust funds, CBO's newest projections indicate an earlier expected insolvency date than was previously estimated. CBO's ten-year budget projections from March – which did not incorporate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic crisis – projected the HTF would deplete its reserves in 2022, the HI trust fund in 2026, the SSDI trust fund in 2028, and the OASI trust fund in 2032.

What Will Happen to the Major Trust Funds?

| Trust Fund | Exhaustion Date | Deficit in Exhaustion Year (% of GDP) | Percent Cut at Insolvency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highway Trust Fund (combined) | FY 2021 | $16 billion (0.1% of GDP) | 25% |

| Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund | FY 2024 | $54 billion (0.2% of GDP) | 17% |

| Social Security Disability Insurance Trust Fund | FY 2026 | $20 billion (0.1% of GDP) | 11% |

| Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund | CY 2031 | $524 billion (1.6% of GDP) | 25% |

Source: Congressional Budget Office and CRFB calculations.

These earlier depletion dates are driven by declining gas tax revenue as a result of reduced driving, declining payroll tax revenue as a result of higher unemployment and lower wages, lower interest rate payments on trust fund reserves, and more disability applications — all stemming from the current public health and economic crisis. These factors are partially offset by savings from lower Medicare and Social Security benefits and smaller cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs), slower assumed growth in health care costs, and higher mortality rates.

Highway Trust Fund

The Highway Trust Fund supports mass transit, road construction, and other surface transportation projects. It is largely funded by the current 18.4-cent-per-callon gas tax (and 24.4-cent-per-gallon diesel tax), which has been frozen in terms of nominal dollars since 1993 and is set to expire in September, 2022. Meanwhile, highway spending has been increasing at the rate of inflation or faster, resulting in a growing structural imbalance between spending and revenue. While recent general revenue transfers have helped keep the HTF afloat, they have not been enough to remedy this fundamental structural imbalance.

In March, CBO projected that the HTF faced a ten-year shortfall of $189 billion, and that it would deplete its reserves sometime in FY 2022 under current law. After incorporating the impact of COVID-19, the agency now estimates the HTF faces a shortfall of $192 billion and will deplete its reserves in FY 2021. Absent new legislation, CBO estimates that highway spending will be cut by 25 percent immediately upon insolvency of the HTF. Still, the gap between highway spending and revenue will continue to grow, ultimately requiring a 38 percent benefit cut by 2030.

Luckily, there are numerous policy options lawmakers could explore that would shore up the HTF’s finances, many of which are featured in our Budget Offsets Bank, our 2015 illustrative plan for the Highway Trust Fund, and a CBO options report from this year. For example, Congress could raise the gas and diesel tax by 15 cents next year and index it to inflation thereafter, or impose a per-mile freight tax on trucks and rail. Other revenue options include enactment of a per-cent Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) tax on commercial trucks or a per-cent VMT tax on all vehicles. On the spending side, policymakers could limit annual federal highway spending to the amount of incoming revenue and require states to cover the difference, freeze spending growth, or eliminate lower-priority spending. With the HTF's depletion date quickly approaching, a one-time general revenue transfer would likely be needed to bridge the phase-in of a solvency plan. Any such transfer should and could be offset with other spending cuts or revenue.

Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund

The Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund makes payments to hospitals and providers of post-acute care services under Medicare Part A. It is largely funded by a 2.9 percent Medicare payroll tax (3.8 percent for certain high-income earners), but also receives income from taxes on Social Security benefits, premiums, amounts recovered from overpayments to providers, fines, penalties, and other transfers and appropriations.

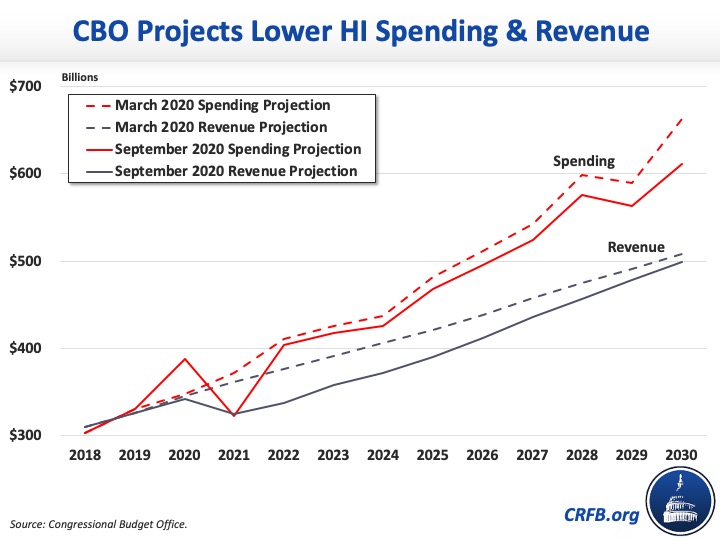

In March, CBO projected that the HI trust fund faced a cumulative shortfall of $516 billion through 2030, and would exhaust its reserves sometime in FY 2026 under current law. CBO's latest projections show a larger ten-year shortfall – about $600 billion – and estimate insolvency will occur much earlier, in FY 2024.

CBO projects the Medicare payroll tax will raise almost $300 billion less over the next ten years as a result of lower wages, and that spending in 2020 will be about $40 billion higher as a result of advanced Medicare Payments. But over the rest of the decade, CBO projects spending to be $226 billion lower as a result of reduced price levels and a weaker economy.

Absent new legislation, Medicare spending will be cut by 17 percent immediately upon insolvency – a cut that will rise further, to 19 percent by 2030. Fortunately, several policy options exist to save the HI trust fund, many of which have been put forward in current and past presidential budget proposals. Others are available in our Budget Offsets Bank. For example, raising the 2.9 percent payroll tax by 0.1 percentage points per year up to 4.0 percent would assure solvency through at least the early 2030s. Other revenue options – including broadening the base of the payroll tax – could also strengthen the trust fund.

On the spending side, there are numerous options to reduce costs in the Medicare program, many of which enjoy broad bipartisan support. For example, policymakers could reduce excessive payments for post-acute care or bad debts, or change the way Medicare pays for Graduate Medical Education and uncompensated care. In addition to the many options that already exist, new ones are currently being developed by our Health Savers Initiative.

Social Security Trust Funds

Social Security is the largest federal spending program, distributing over $88 billion in monthly benefits to nearly 65 million beneficiaries. Benefits are paid through the Disability Insurance (DI) trust fund and the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund, which are both primarily funded by the 12.4 percent payroll tax. Previously, CBO projected the DI trust fund would deplete its reserves in FY 2028 and the OASI trust fund in FY 2032. Now, CBO projects the DI trust fund will become insolvent in FY 2026 and the OASI trust fund in calendar year 2031 – when current 56-year-olds reach the full retirement age and today’s youngest retirees turn 73. The Social Security Trustees estimate a later insolvency date, though they have not updated their projections to reflect the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic crisis.

Absent new legislation, disability benefits will be cut by 11 percent immediately upon insolvency of the DI trust fund. The gap between spending and revenue would actually decrease thereafter as revenues are projected to exceed costs, requiring only a 5 percent benefit cut in 2030. Meanwhile, OASI benefits would be cut by approximately 25 percent immediately upon insolvency of the OASI trust fund.

Like the HI trust fund, the Social Security trust funds are critically dependent on payroll tax revenue, which has significantly declined due to skyrocketing unemployment and depressed wages. Even though lower inflation and wages reduced CBO's projections of Social Security spending by nearly $500 billion over the next ten years, they also resulted in revenue projections that are lower by more than $800 billion. Combined with reduced interest rates paid on trust fund reserves, these changes have significantly weakened the program's finances.

Once the current crisis passes, policymakers must turn their attention to restoring long-term solvency for the Social Security program. The longer policymakers wait, the more costly and painful necessary adjustments will become. Fortunately, many options exist to secure Social Security well into the future. Lawmakers could adjust the payroll tax rate, expand the tax base, modify the initial benefit level, the cost of living adjustment, or the retirement ages. Previously proposed legislation, including the Social Security 2100 Act from the left, the Social Security Reform Act from the right, and the Conrad-Lockhart Bipartisan Policy Center plan from the center, would all restore sustainable solvency, as would a proposal from Maya MacGuineas, Marc Goldwein, and Chris Towner to design a Social Security system that better promotes economic growth.

Our Social Security Reformer tool allows anyone to design their own plan.

*****

Securing long-term solvency of the Highway, Medicare, and Social Security trust funds will require the will to act and negotiate tradeoffs inherent in these efforts. Legislation like the TRUST Act would help by establishing bipartisan and bicameral commissions to address each threatened trust fund.

While policymakers are rightly focused on the response to the current crisis, it is imperative that they turn their attention to saving these vital trust funds from insolvency once it passes. The longer action is delayed, fewer solutions will be available and necessary adjustments will be much more costly and painful.