Is a Buy-In the Bipartisan Answer to Raising the Medicare Age?

Last week we discussed the potential for bipartisan agreement on Medicare cost-sharing reforms, and today Politico reports on another area of entitlement reform where lawmakers may be able to reach middle ground: raising the Medicare age. The article points to a recent Urban Institute report which proposes raising the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 67, aligning it with Social Security, while also allowing 65- and 66-year olds to buy into the Medicare program with subsidies for low- and middle-earners. This addresses some of the chief concerns of raising the age that it would leave many seniors uninsured, be particularly harmful for lower income seniors, and increase overall health costs.

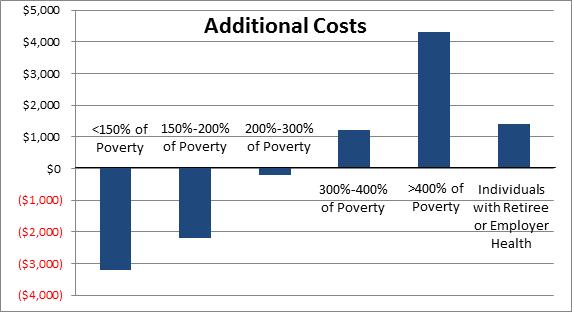

The way this could work is that once the Medicare age is raised to 67, seniors age 65 and 66 would be offered an actuarially fair "buy-in" so they could continue to receive Medicare benefits. The upper half of the income earners would pay the full cost of their benefits, while those with incomes below 400 percent of the poverty line would receive income-related subsidies similar to those provided under the Affordable Care Act. Additionally, seniors below 133 percent of the poverty line -- who would generally qualify for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act -- would instead receive a full Medicare premium subsidy.

Dr. Robert Berenson, a past vice-chairman of the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MedPAC) and one of the authors of the Urban proposal explains:

“We begin with the understanding that life expectancy has increased since Medicare was established in 1965, and it’s reasonable to raise the eligibility age, just as we have with Social Security…But it’s not reasonable to leave people unprotected in the private market. So we think it’s best to allow them to buy in to the best deal, Medicare. And that establishes continuity for them when they reach 67 and are eligible.”

On the one hand, a Medicare buy-in still addresses the issue of population aging, which is the largest driver of entitlement spending growth over the next few decades. It would extend the life of the Medicare program and stave off untargeted, across-the-board cuts when the program is scheduled to become insolvent in 2024. Berenson notes that since its inception, Medicare eligibility has remained unchanged while life expectancy after age 65 has increased and health care costs have skyrocketed. In 1970, people turning 65 could expect to live another 15 years on average, spending 24 percent of their adulthood on Medicare; whereas people turning 65 today can expect to live another 20 years, spending 30 percent of adulthood on Medicare.

On the other hand, a buy-in provides a coverage option for those 65- and 66-year olds who may not have access to health insurance. Moreover, it offers subsidy assistance parallel to that under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) for low and middle income seniors to afford Medicare coverage for two years before aging into the program at 67. This provides a progressive subsidy structure, targeting resources to whose who need it most. Raising the Medicare age on its own was found to help the most disadvantaged. Adding a Medicare buy-in as the Urban proposal describes would lead to an even better distribution since Medicare costs are expected to be lower than exchange costs and since they call for some additional subsidies for those above 400 percent of the poverty line.

Another concern of raising the Medicare age has been the impact 65- and 66-year olds would have in the ACA exchanges with rules allowing insurers to charge older enrollees up to three times what they charge younger enrollees. More broadly, one study has suggested that raising the age would increase total health care spending by pushing people into higher cost private plans or uncompensated care. However, creating a Medicare buy-in helps to mitigate these rate and cost-shifting issues to a significant degree. It also provides a mechanism for younger, and therefore typically healthier, seniors who currently help to bring down average Medicare costs enroll in Medicare while still raising the age and alleviating budgetary pressure.

Urban’s proposal offers just one approach to raising the Medicare age. Overall, the authors estimate their proposal would save $90 billion over ten years. While this is less than estimates for raising the Medicare age without a buy-in, there is room to dial the policy to be more or less generous depending on policy and savings goals. For example, lawmakers could lower the subsidy assistance, allow for a buy in option at age 62, or index the retirement age to longevity after raising it to 67. We shared estimates for some of these options in our Health Care and Revenue Savings Options report last December.

It's encouraging to see these types of ideas that could garner bipartisan support gain more interest as lawmakers get ready to return from recess and restart negotiations on a budget deal. It is certainly not the silver bullet for reforming Medicare, as health care cost growth will continue to be an issue, but it is a policy that warrants fair consideration. Let’s hope this is a sign they can come together on real entitlement reform that could help put our debt on a downward path as a share of the economy.