The Urban Institute's $600 Billion Medicare Reform Package

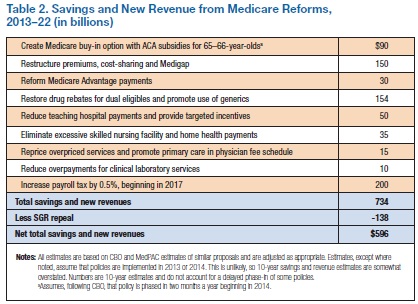

The Urban Institute's Robert Berenson, John Holahan, and Stephen Zuckerman recently released a very useful paper entitled "Can Medicare Be Preserved While Reducing the Deficit?" The paper presents a number of Medicare reforms for beneficiaries, providers, and health insurance plans, with gross savings of $735 billion and savings of $600 billion net of a repeal of the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula.

Of the total gross savings, $535 billion comes from the spending side, and $200 billion comes from additional revenue. The authors detail a number of ways that Medicare costs could be reduced by better targeting resources towards beneficiaries who need them more, by encouraging lower-cost options and greater price sensitivity, and by reducing provider payments where services are overvalued.

First, the authors present three findings about Medicare:

- Although Medicare spending is estimated to grow at 6 percent a year, the problem is not program inefficiency. Rather, it is the combined effect of annual enrollment growth of about 3 percent and a similar rate of growth in spending per enrollee—the latter is lower than commercial health insurance.

- There is no evidence that competition among private health plans, alongside or replacing Medicare, would decrease costs. Medicare Advantage plans have lower costs than traditional Medicare in only about 15 percent of counties, representing 30 percent of Medicare Advantage spending. In all other counties, Medicare Advantage plans have costs equal to or greater than traditional Medicare.

- Medicare has led payment reform in the past and continues to do so. From the implementation of the inpatient prospective payment system in 1984 to the myriad of prospective payment systems for other services, Medicare has created payment systems that have been adopted by other payers and hold the potential for further spending reductions.

Their package of reforms includes:

- Medicare age increase with buy-in: To address changing demographics, the authors recommend increasing the Medicare age to 67. However, for those age 65 and 66, they would offer an actuarially fair "buy-in" so seniors above 65 could continue to receive Medicare benefits. For the top half of the income spectrum, 65- and 66-year olds would pay the full cost of their benefits. Those with incomes below 400 percent of the poverty line would receive subsidies equal to those provided under the Affordable Care Act. Those making below 133 percent of the poverty line -- who would generally qualify for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act -- would instead receive a full Medicare premium subsidy from the federal government. By having a buy-in plus subsidies for lower-income people, the authors address two common critiques of the Medicare age increase. Overall, they expect this proposal would save $90 billion over ten years.

- Restructured cost-sharing and premiums: The report, like many other reform plans, would restructure Medicare's cost-sharing in a number of ways. First, they would have a single income-related deductible for Parts A and B. It would be higher than the current deductibles for people over 400 percent of the poverty line, about the same for people between 300 and 400 percent, and lower for people below 300 percent. Second, they would raise Part B and D premiums from about 25 percent of program costs to 40 percent, again limiting premiums to a similar amount by which they would be limited with the premium tax credits in the Affordable Care Act. Third, they would have an out-of-pocket cap on total cost-sharing again based on income. For example, the cap could be $6,000 for people at 400 percent of the poverty line or higher, gradually reducing to zero for people at or below 133 percent. Finally, they would limit Medigap supplemental coverage of cost-sharing by, for example, prohibiting Medigap from covering the first $500 and 50 percent of the next $4,950. They estimate these reforms could save $150 billion.

- Medicare Advantage benchmark reductions: The Affordable Care Act reduces Medicare Advantage (MA) benchmarks, which determine how much insurance plans are paid in Part C, to 95, 100, 107.5, and 115 percent of traditional Medicare's costs for counties with the highest to lowest costs, respectively. Although this does reduce overpayments in MA, the authors would go further. Instead of this schedule of benchmarks, they would have benchmarks be set at 95 percent of traditional Medicare's costs for the highest cost areas and 100 percent for everyone else. They estimate this would save $30 billion.

- Prescription drug rebates and reforms: The authors would take two main steps to reduce prescription drug costs in Part D. For one, they would expand drug rebates that drug manufacturers currently provide to Medicaid to dual eligibles in Medicare as well, savings $137 billion over ten years. Second, they would encourage substitution of generic drugs for brand-name drugs for people with subsidized cost-sharing in Part D (people below 135 percent of the poverty line) by eliminating cost-sharing for generic drugs and having a $6 co-payment for substitutable brand-name drugs. This would save an estimated $17 billion.

- Reductions in certain provider payments: The authors propose reducing spending on indirect medical education (IME), which pays for clinical costs associated with graduate medical education (GME). They would significantly reduce spending on IME and re-orient the program to incentivize training physicians to provide higher-value, lower-cost care, saving $50 billion. The authors also would reduce payments to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and home health agencies (HHAs), two groups of providers that currently have very high profit margins. Rather than just lowering payments, they would also create a shared savings factor which would allow SNFs and HHAs to keep a share of payments that exceed their actual costs. This policy could save $35 billion.

- Reforms to physician payments: Naturally, the authors would repeal the SGR formula, which sets physicians up for a 25 percent cut in payments next year, costing $140 billion. To replace the system, they would target areas where services are misvalued and payment differentials based entirely on where a service is performed. For one, they would reduce fee schedules for non-primary care physicians by 6 percent over three years and leave them flat for the next seven, saving $15 billion. To address the latter problem mentioned above, they would reduce payments for hospital outpatient services to be roughly equal with those for physicians performing the same services outside a hospital setting. Payments for services that are exclusively performed in a hospital would be increased. Finally, payments for clinical labs would also be reduced, since the marginal cost of tests are generally small. Overall, these reforms would save $25 billion.

- Hospital Insurance (HI) tax: Recognizing the role that the aging of the population has in the growth of Medicare spending, the authors suggest compensating for the rise in beneficiaries by raising the Part A's funding source, the HI tax, by 0.5 percent starting in 2017. This would raise $200 billion through 2022.

This paper includes a number of targeted and thoughtful reforms to reduce Medicare spending. Policymakers would be wise to take notice, as these proposals could be very useful. They should certainly be on the table, along with the numerous other health care reforms that have been proposed in recent years.