Bonus Depreciation Has Cost Over $200 Billion So Far and Could Cost $450 Billion

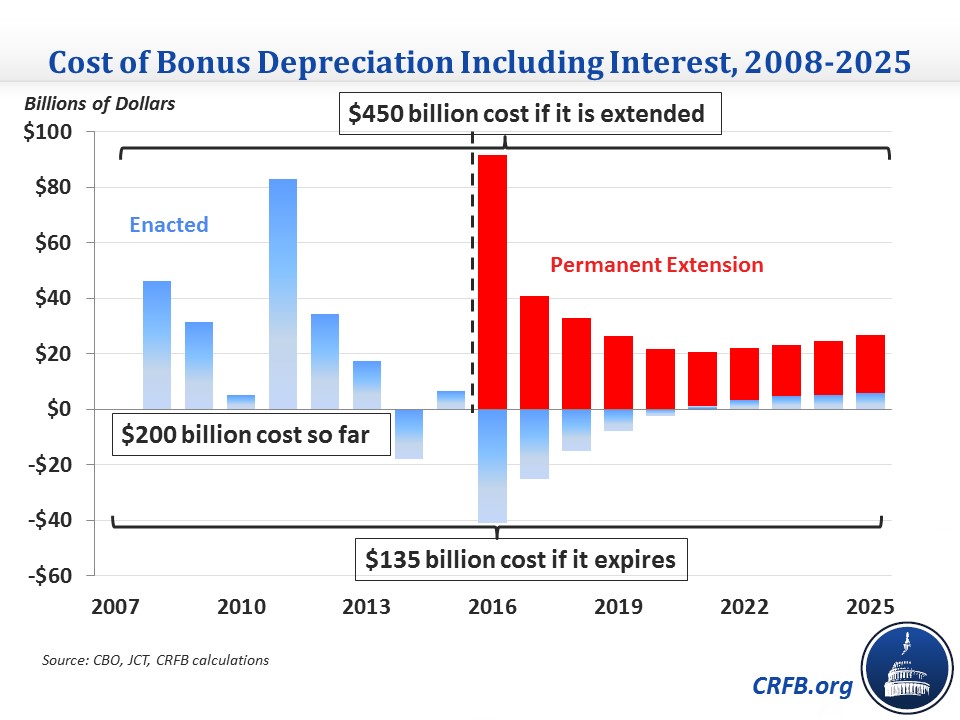

With Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) being elected as Speaker of the House, the Ways & Means (W&M) Committee Chair has gone to Rep. Kevin Brady (R-TX). In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Brady said that lawmakers should permanently extend a select group of tax extenders, the 50-plus provisions that expired at the end of 2014 that are temporarily extended year after year. It is quite possible that one of the policies permanently extended is bonus depreciation, which the Ways & Means Committee voted to permanently extend and expand in September. This provision, which has been used several times during recessions, was most recently reinstated in 2008 and has since been extended six times. It has cost over $200 billion through 2015 and will cost about $450 billion through 2025 if it is permanently extended.

Bonus depreciation allows businesses to write off 50 percent of the cost of capital investments immediately (the rest is deducted over time according to normal depreciation schedules). It was originally enacted and has been extended temporarily to provide stimulus while the economy is weak. Because bonus depreciation is largely a timing shift, a one-year extension would have substantial immediate costs that would be largely recovered over time, but a permanent extension would cost $245 billion over ten years (the W&M version costs $280 billion).

From 2008 through 2015, bonus depreciation has cost $200 billion (including interest), and that doesn't even include the cost of extending the provisions for 2015. If bonus depreciation remains expired, that cost would be partially recovered over time as businesses would not be able to take the deductions they have already accelerated, leading the total cost to fall to $135 billion by 2025. However, if it is extended permanently, bonus depreciation would cost nearly $450 billion through 2025.

Note that these numbers do not get much better when including economic effects. The Joint Committee on Taxation recently released a dynamic score of the Ways & Means version of bonus depreciation showing that the economic boost would only offset about 5 percent of the revenue loss of a permanent extension, reducing the ten-year cost from $280 billion to $265 billion.

Aside from budgetary concerns, there are a few reasons why bonus depreciation shouldn't simply be extended permanently or packaged with other tax extenders. As we've mentioned before, bonus depreciation was enacted as temporary stimulus, so if lawmakers are considering a temporary tax extenders package, its inclusion should be evaluated based on the need for further stimulus. Even then, the Congressional Research Service and others do not view the provision as effective stimulus.

There is an argument that bonus depreciation should be made permanent as a way to encourage investment and thus longer-term economic growth. However, doing this in isolation could lead to hugely negative tax rates on investments funded by borrowed money due to the ability to deduct interest costs. To avoid a big incentive to overleverage to finance investments, lawmakers should permanently extend bonus depreciation only in the context of tax reform that eliminates or substantially reduces the interest deduction.

It is important that lawmakers treat bonus depreciation more carefully rather than as just another tax extender to be perpetually continued or made permanent. It is the single most costly extender and is a temporary provision because it was intended to be economic stimulus in a weak economy. Making it permanent would undermine that purpose and could increase the incentive to borrow if not done in the context of tax reform. Most of all, policymakers should not think that they can extend bonus depreciation for free; it should be paid for.