Updating the Cost of Delay for Social Security

Click here to read the original paper on the cost of delay for Social Security.

Click here to see an updated version of this analysis for 2015.

The Social Security Trustees recently showed what it would take to make Social Security solvent over 75 years: immediately raise everyone’s taxes by over 2.8 percentage points, immediately cut everyone’s benefits by 17 percent, or cut benefits for new beneficiaries immediately by 21 percent. They also warn that those costs will go up substantially if our leaders in Washington procrastinate. Indeed, waiting until 2033 will increase the needed adjustments by 50 percent. As they explain:

If substantial actions are deferred for several years, the changes necessary to maintain Social Security solvency would be concentrated on fewer years and fewer generations. Much larger changes would be necessary if action is deferred until the combined trust fund reserves become depleted in 2033.

The Trustees make clear that there are two costs to waiting.

First, interest accumulates in the trust fund so changes made sooner have a greater effect than the same change made in later years. Second, taking action sooner allows the burden of changes to be spread out over more people, lessening the burden on future generations. In a paper last August, we demonstrated arithmetically how changes became larger and different conditions became harder to maintain the longer policymakers wait to act. In other words, policymakers will have less tools available.

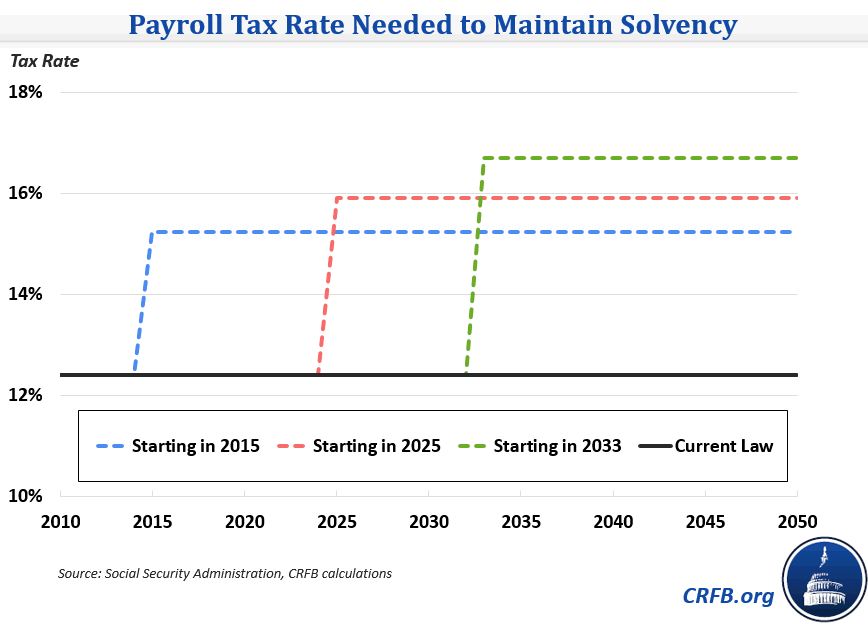

As mentioned above, maintaining solvency over 75 years by increasing payroll tax rates would require a 2.83 percent immediate payroll tax increase. Waiting ten years would raise that rate increase to 3.5 percent (for a 15.9 percent total rate), and waiting until 2033 would raise the rate increase to 4.3 percent (for a 16.7 percent rate). Delaying the rate increase also effectively exempts those close to retirement and puts more of the burden on younger workers.

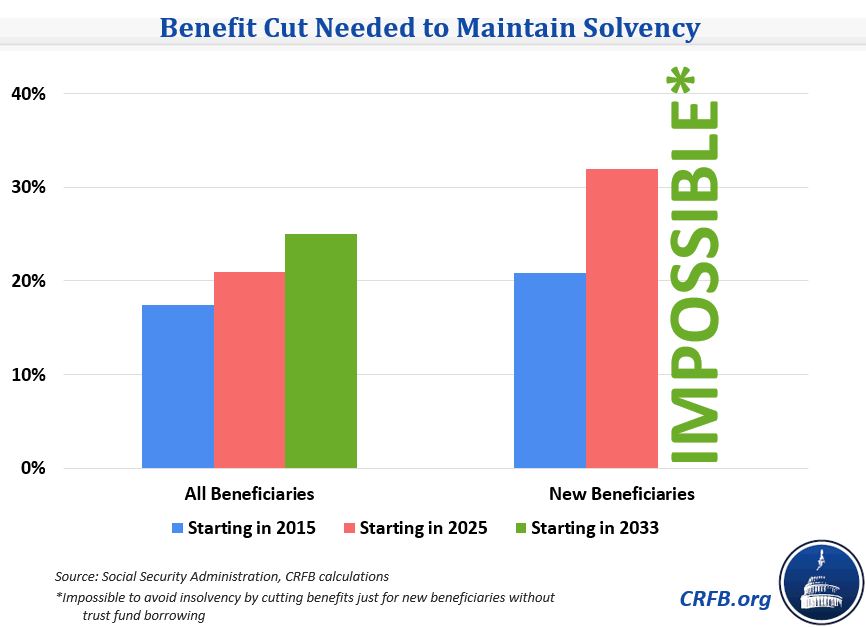

As for benefit cuts, the necessary cut to maintain 75-year solvency is 17.4 percent if applied to all beneficiaries and 20.8 percent if applied only to new beneficiaries. The cut for all beneficiaries would climb to 21 percent in ten years and 25 percent by 2033. For new beneficiaries, the cut would climb to 32 percent in ten years, then would rise rapidly until 2031, when it would no longer be possible to maintain trust fund solvency even by eliminating benefits entirely for new beneficiaries. It should be noted also that these numbers assume cuts are applied to beneficiaries uniformly, but most reform plans protect low-income retirees.

In our paper last year, we showed two other dimensions of the cost of waiting. First, we are only five years away from being unable to close the shortfall entirely with benefit reductions while ensuring that real benefits do not decrease over time. Second, waiting to make changes gives people less time to prepare and makes it harder for them to make up benefit losses with personal savings; for example, a person making $50,000 would have to set aside about 1% of their income per year starting this year to offset a 10% benefit cut in 2050, but they would have to set aside more than 2.5% per year if they started 20 years later.

Waiting until the last minute has become commonplace for decision-making in Washington, but lawmakers should not throw away the time they have for Social Security. If they use it wisely and start now, they have a much easier constructing a smart reform plan that better protects low-income and current retirees and gives others time to plan for changes.