The Tax Break-Down: Intangible Drilling Costs

This is the eleventh post in our blog series, The Tax Break-Down, which will analyze and review tax breaks under discussion as part of tax reform. Our last post was on the American Opportunity Tax Credit, which provides a credit for undergraduate tuition.

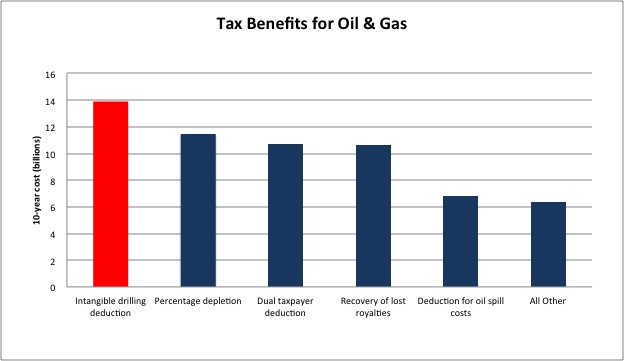

Intangible drilling costs are one of the largest tax breaks available specifically to oil companies, allowing companies to deduct most of the costs of drilling new wells in the United States.

In order to determine taxable income, U.S. businesses can normally deduct expenses from revenues so they are only taxed on profits. Under normal income tax rules, a company that pays expenses in order to make future profits would need to deduct the expenses over the same time period as profits. The costs for drilling exploratory and developmental wells would need to be deducted as resources are extracted from the well.

The break for intangible drilling costs (IDCs) is an exception to the general rule. Independent producers can choose to immediately deduct all of their intangible drilling costs. Since 1986, corporations have only been able to deduct 70% of IDCs immediately, and must spread the rest over 5 years.

Intangible drilling costs are defined as costs related to drilling and necessary for the preparation of wells for production, but that have no salvageable value. These include costs for wages, fuel, supplies, repairs, survey work, and ground clearing. They compose roughly 60 to 80 percent of total drilling costs.

The deduction for intangible drilling costs has been permitted since the beginning of the income tax code, in order to recognize the risks involved in drilling developmental wells—not every well strikes oil. Only IDCs associated with domestic or offshore wells may be deducted; foreign wells cannot be expensed in this way.

How Much Does It Cost?

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), the tax break for intangible drilling will cost roughly $1 billion in 2013, and $16 billion over the next decade. This is the largest tax preference specifically for oil and gas and totaled about 8 percent of the total value of tax preferences for energy and natural resources in 2013. In contrast, expensing for exploration and development costs for nonfuel minerals (like coal) will cost $0.1 billion in 2013, and $1 billion over the next decade.

What are the Arguments For and Against the Deduction for Intangible Drilling Costs?

Supporters of the deduction argue that oil and gas and exploration and development is a high-cost industry, and allowing expenses to be recovered immediately encourages companies to invest. They explain that altering the deduction could result in job losses, since wages are included in the deduction.

More broadly, supporters point out that the oil and gas industry receives the same treatment that other manufacturing or extractive industries receive, and are merely a target because of the now-controversial nature of reliance on fossil fuels. Finally, supporters of energy independence often support the IDC deduction, as it promotes further exploration and development of wells within the United States.

Opponents argue that since this tax provision was introduced over a hundred years ago, technology has advanced to the point where dry wells are less of a problem. The success rate of striking oil (or gas) is about 85%, which means producers are spending less on exploring wells that won’t become profitable.

More generally, opponents say that oil prices are expected to remain high, and that demand continues for oil and other fossil fuels. They believe there is no need to subsidize an industry that is already booming.

What are the Options for Reform?

President Obama has continually proposed repealing the break for intangible drilling costs in his yearly budgets, a proposal also suggested by Senator Sanders and Representative Ellison. Fully repealing this tax break would raise $14 billion through 2023, though importantly would largely represent a timing shift, and raise only about $100 million in 2023 alone. A number of other tax reform plans, including the Domenici-Rivlin plan, the Simpson-Bowles plan, and the Wyden-Gregg/Coats plan would also repeal the preference for IDCs.

Alternatively, the deduction could be repealed for most wells, but still allow a company to deduct costs for unproductive dry wells, raising $10 billion. Or, the deduction could only be eliminated for the five biggest oil companies, raising $2 billion over ten years.

If the deduction were repealed, drilling costs would need to be treated like other depletable property, deducted over the life of the well.

| Options for Reforming the Expensing of Intangible Drilling Costs | |

| Options | 2014 - 2023 Revenue |

| Repeal expensing for all extractive industries, including oil, gas, coal, and other hard mineral mining | $18 billion |

| Repeal intangible drilling cost expensing for oil and gas companies completely | $14 billion |

| Repeal intangible drilling cost expensing for oil and gas companies, only for C-Corporations | $10 billion |

| Repeal expensing for the 5 largest oil producers | $2 billion |

| Keep expensing only for dry wells | $10 billion |

Where Can I Read More?

- Joint Committee on Taxation – Description Of Present Law And Select Proposals Relating To The Oil And Gas Industry

- Internal Revenue Service – Intangible Drilling Costs Deduction

- American Petroleum Institute – Repeal Intangible Drilling Costs (Discussion)

- Center for American Progress – Big Oil’s Misbegotten Tax Gusher

- The Atlantic – America’s Most Obvious Tax Reform Idea: Kill the Oil and Gas Subsidies

- American Enterprise Institute - The Truth About All Those "Subsidies" for "Big Oil"

* * * * *

The deduction for intangible drilling costs allows oil and gas producers to deduct most of the costs associated with finding and preparing wells. When the deduction was created in 1913, it was intended to attract business to the costly and risky business of oil and gas exploration. Some argue that technology has advanced enough that locating wells is no longer as costly, and this deduction is an unneeded subsidy to a profitable oil industry. Others argue the deduction is an important way to support the domestic energy industry and promote energy independence. As part of tax reform, policymakers will need to decide whether to keep this incentive for energy production, or repeal it in favor of lower tax rates or a lower deficit.

Read more posts in The Tax Break-Down here.