SGR Plan Will Likely Increase, Not Reduce, Long-Term Debt

Note: The analysis below is based on an earlier version of the SGR plan, which has since been adjusted to include modestly larger offsets and – more significantly – slower growth in physician payments beyond 2025. Our latest analysis shows that debt would increase by $500 billion by 2035.

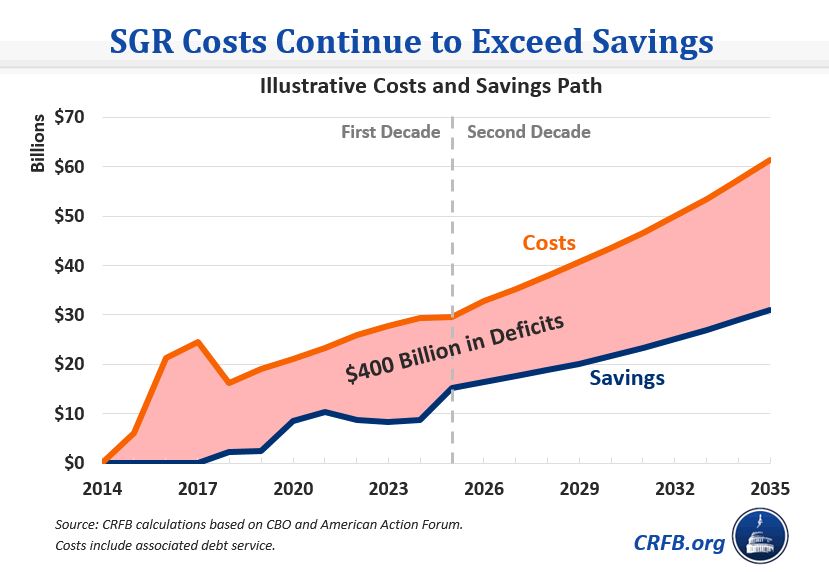

Proponents of the SGR reform plan currently under discussion have suggested that lawmakers ignore its $140 billion ten-year cost and focus instead on the legislation’s long-term effects. Over time, they argue, spending reductions in the legislation will grow and thus reduce long-term debt levels. Unfortunately, this claim appears to be false – the legislation would add to the debt both this decade and next. Even accepting optimistic savings estimates, we estimate that debt would increase $400 billion by 2035 (including the cost of interest) as a result of this deal.

According to recent reports, the SGR reform bill currently under consideration would cost about $210 billion through 2025, while offsetting $65 billion – leading to about $140 billion of net costs. Some have argued that the savings will grow over time and thus the legislation will be fiscally responsible over the long-run. Yet while it is true that the savings will be greater in the second decade, costs will grow as well – and under the current framework, costs will most likely remain higher than savings in the second decade as well as the first.

In other words, proponents of the “second-decade theory” appear to be looking only at one side of the ledger. They are counting the long-term savings while ignoring the long-term costs.

To the plan's credit, Medicare savings from the offsets in the reform package will grow over time. Although some of the savings are temporary, some of the changes are not only permanent but will likely save much more in the second decade than the first, including changes to post-acute care payments, Medicare means-testing, and Medigap reform. (Importantly, much of the reason is not because the savings grow faster over time, but because these policies don’t begin for a number of years and therefore generate savings over less years in the first decade than the second).

According to one estimate by Doug Holtz-Eakin of the American Action Forum, Medicare means-testing and Medigap reform could save $230 billion in the second decade. Notably, these numbers appear to us to be significantly higher than likely savings, but even accepting these numbers, total savings over two decades would be about $300 billion.[1] Meanwhile, the total costs could total more than $550 billion.

Why are total costs so much higher than the savings? As a starting point, the SGR plan under discussion would cost about $210 billion in the first decade alone. But beyond that, it would continue to replace scheduled SGR cuts in the law with continued growth in annual payment updates. The reported bill would also permanently extend qualifying individual (QI) assistance. Although no official estimate exists, we conservatively estimate second-decade costs would be in the broad range of $350 billion, perhaps higher.

On top of this cost, near-term (and long-term) costs that exceed savings will require additional interest payments on the nation’s debt. By our calculation, net interest payments under the plan (assuming the American Action Forum savings numbers) would total nearly $140 billion through 2035. The total of $550 billion of direct costs plus $140 billion of added interest is significantly higher than $300 billion of savings. The result – under this SGR plan, debt could be roughly $400 billion higher by 2035, and would continue to grow beyond that.

To be sure, our estimates are very rough – and we hope the Congressional Budget Office will release more accurate projections soon. But certainly, it does not appear this plan would come even close to paying for itself over the long-term.

In the coming days, we’ll put forward ideas to fix that.

For now, policymakers don’t need to settle – they need to lead.

[1] Note that Holtz-Eakin’s estimates exclude the long-term effect of changes to post-acute care payments. But they also appear to significantly overstate savings for means-testing and Medigap reform relative to our back-of-the-envelope estimates. For purposes of this blog, we assume these savings estimates are accurate on net.