NYT Gets It Wrong on Social Security (Again)

This weekend, The New York Times (NYT) editorial board laid out an argument for why they believe Social Security’s long-term gap is relatively manageable, that any solution should come mainly on the revenue side to offset cuts already in place, and that their readers should beware of “the deficit-obsessed, anti-tax world of Washington [where] closing the shortfall in Social Security has come to mean broadly cutting benefits.”

We certainly agree with the sentiment that Social Security is a manageable problem. As CRFB Policy Director Marc Goldwein explained, "Reforming Social Security is easy – but it won’t be for long," and CRFB's new interactive tool, The Reformer, highlights this point well. Unfortunately, this is one of the few facts the NYT piece gets correct. Once again, many of the NYT's claims do not stand up to scrutiny.

The NYT attack on across-the-board cuts is an attack on a strawman. The NYT warns about “those who promote across-the-board cuts” who they argue "are not interested in strengthening the system." Yet no Social Security solvency plan out there proposes such a policy. To be sure, there are elements of various plans which have the effect of modifying benefits roughly across-the-board (though these policies tend to achieve other policy goals such as measuring inflation more accurately or encouraging longer working lives). But comprehensive reform plans tend to combine these policies with various other reductions, enhancements, and revenue provisions aimed at achieving broader overall distributional goals.

The graph below shows how a few reform plans affect scheduled benefits in 2050 by earner, also displaying what would happen to benefits if the Social Security trust fund were allowed to be exhausted.

Percent Change in Scheduled Benefits in 2050

Source: SSA

Update: graph has been updated to include additional earners in the distributional analysis.

Indeed, the only across-the-board benefit cut plan out there is the status quo. Failure to act to make Social Security solvent would result in a 23 percent across-the-board cut to new and current beneficiaries.

NYT mischaracterizes benefits as shrinking. In arguing against significant changes to Social Security benefits, the Times argues that “the focus on benefit cuts also conveniently ignores the fact that benefits are already shrinking,” citing the increase in the normal retirement age from 65 to 67 already scheduled (and underway) under current law. Yet benefits are NOT shrinking; the increase in the age simply means they are growing slightly more slowly. Continued improvement in life expectancy means that lifetime benefits are growing over time as retirees are able to collect benefits for more and more years. Indeed, whereas a retiree at the normal age would have collected benefits for an average of 14 years in 1940, (s)he will collect for 19 years in the year 2000. The increase in the age from 65 to 67 simply holds the average number of years in retirement to an average of 19.3 through 2025, after which growth will continue.

Comparing Life Expectancy at 65 with Retirement Ages

Source: SSA

In addition, real annual benefits are growing from cohort-to-cohort since the benefit formula itself causes initial benefits to rise as wages do. In fact, the initial benefit for a person retiring at the normal retirement age has increased from about $17,300 twenty years ago to $19,500 in 2013 and will rise to about $22,600 twenty years from now (in 2013 GDP price index-adjusted dollars). Average lifetime benefits will grow similarly from about $313,000 in 1993 to $377,000 in 2013 and $443,000 twenty years from now.

Average Initial and Lifetime Benefits (2013 GDP Price Index-Adjusted Dollars)

Source: Authors calculations based on SSA, BLS, and OMB. Real benefits calculated using GDP deflator.

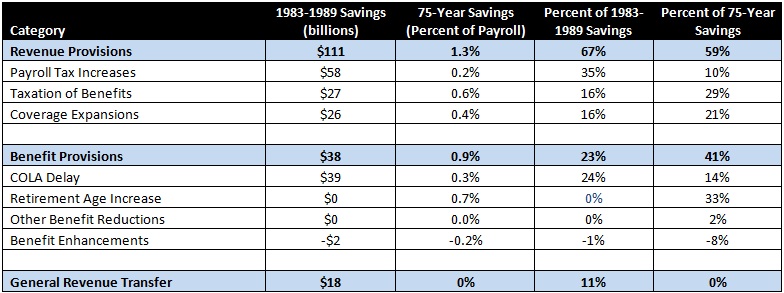

NYT tells only half the story on the 1983 reforms. The Times makes the case that substantial benefit cuts already underway should be balanced primarily with revenue increases, suggesting that the 1983 Social Security reforms were mainly focused on benefit reductions. In reality, the bipartisan reforms agreed to in 1983 included a mix of spending and revenues adjustments. Indeed, roughly two thirds of the short-term savings and three fifths of the long-term savings in the 1983 reforms came from revenue provisions. If taxation of benefits was counted half as a revenue increase and half as a benefit cut – since it could be thought of as a revenue provision that reduces net benefits – about 45 percent of the long-term savings would be on the revenue side.

Composition of 1983 Social Security Reform

*****

The New York Times argues that “Social Security benefit cuts are already well under way, and they cannot go much further.” Yet just as no one is really talking about across-the-board benefit changes, there are also few plans with significant cuts in benefits. Instead, most Social Security reform plans with benefit changes would slow the growth of benefits – usually progressively – to offset some of the effects of automatically growing benefit levels and increasing life expectancy. Such changes could be (and often are) combined with increases in revenue to help fully fund post-reform benefit levels. Indeed, the policies mentioned by the NYT to increase the cap of taxable wages and pursue immigration reform could be important elements of the solution.

While the Times suggests there is plenty of time to deal with Social Security, the time left to make these sensible adjustments is running out. As Goldwein explains, "In the end, waiting to act will lead to unfair and unnecessarily abrupt changes that would rob today’s workers of the ability to plan and adjust."