It Would Take Nearly Unprecedented Economic Growth to Balance the Budget

Increased economic growth has often been cited as a solution to our fiscal problems or as a way to offset deficit-increasing legislation. However, higher growth has a limited ability to do either of those things, and recent legislation has made this solution even more inadequate.

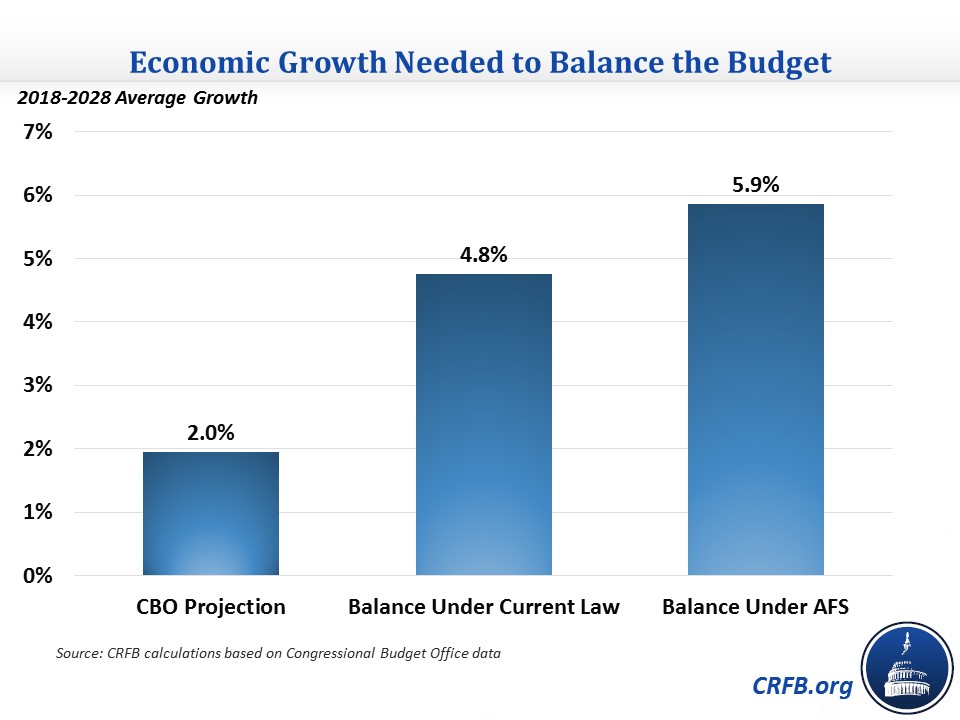

We estimate that balancing the budget through higher economic growth alone would take 4.8 percent average growth over the next decade, or 5.9 percent if temporary tax cuts and spending increases were continued. Even the first amount would be nearly unprecedented for a ten-year period since World War II, and would be nearly two and a half times the average growth that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects for that period. Policymakers cannot rely on growth alone; it will take hard choices on spending and taxes to get to balance.

Our estimate is based on the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO) January 2017 estimate of how a change in economic growth would affect the budget; CBO has not yet updated this estimate for the current baseline, so we make a few adjustments. First, we adjust the estimate of how much revenue is gained to account for the December 2017 tax law, which reduced marginal tax rates and consequently the amount of revenue the federal government would take in from added growth. We also adjust the effect on interest spending due to changes in interest rates to account for the higher debt that is now projected.

CBO projects that real GDP growth will average 2.0 percent over fiscal years 2018-2028. To erase the $1.53 trillion deficit CBO projects for 2028 under current law, growth would need to increase by 2.8 percentage points per year for an average growth rate of 4.8 percent. That would be just about the record level of economic growth over a ten-year period achieved during the 1960s (1959-1968). More recently, this level of growth hasn't been achieved in a single year since 1984. Even getting to 3 percent sustained growth would be extremely difficult, and there is no plausible path to get 4 percent growth.

However, current law contains several optimistic policy assumptions, including the expiration of several tax cuts and spending increases. If policymakers follow the assumptions of CBO's Alternative Fiscal Scenario (AFS), they would need to close a $2.1 trillion deficit in 2028. This would require average growth of 5.9 percent, which is even more implausible than the 4.8 percent growth rate needed under current law. That level of annual growth has only been achieved in a single year once in the past 50 years. Averaging it over ten years would be impossible.

Even an easier fiscal goal would still require a substantial increase in growth. Stabilizing debt at its current level of about 77 percent of GDP through 2028 would require growth of 4.2 percent under current law and 5.2 percent under the AFS.

It is important to be realistic: it is much more likely that lawmakers could increase economic growth by a few tenths of a percentage point, rather than 3 or 4 percentage points, with well thought out and comprenhesive growth policies. Meeting an aggressive fiscal goal like balancing the budget will need to include substantial deficit reduction. Balancing the budget can't rely on increased economic growth to be more than a small part of the solution.