How High Will Debt Rise If Current Policy Continues?

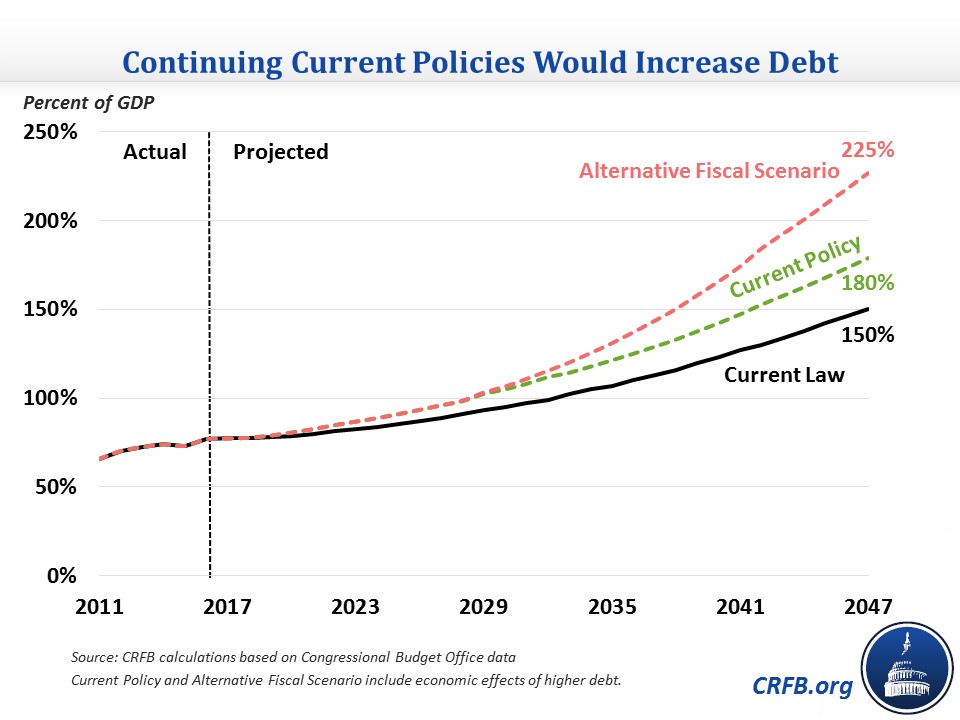

The Congressional Budget Office's (CBO) 2017 Long-Term Budget Outlook shows today's high debt will nearly double as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the next 30 years under current law. Yet as we show in this piece, debt could grow far higher if policymakers continue to act as they have in recent years.

By our estimates, if policymakers simply continue "current policy" on taxes and repeal the discretionary spending sequester, debt would grow to 180 percent of GDP in three decades instead of 150 percent. Under our approximation of CBO's "Alternative Fiscal Scenario," debt would rise to a whopping 225 percent of GDP. Under these scenarios, average income (as defined by real Gross National Product per capita) would also be between 2 and 6 percent smaller than under current law.

For the most part, CBO's baseline represents "current law," meaning that it assumes no new legislation is passed other than what is needed to keep the government functioning as normal. Under our current policy scenario, we further assume that policymakers:

- Offer companies permanent bonus depreciation to deduct 50 percent of all capital expenses immediately, although under current law only a 30 percent bonus will be allowed starting in 2019, and the provision will expire in 2020.

- Permanently extend various temporary tax cuts, most of which either expired at the end of last year and could be revived retroactively or will expire after 2019. Some of these tax breaks include a credit for wind power production, an exclusion for mortgage debt forgiveness, and the new markets tax credit.

- Permanently repeal three health care taxes in the Affordable Care Act that are currently on hiatus – the medical device tax, the health insurer tax, and the "Cadillac" tax on high-cost health insurance.

- Permanently repeal the sequester on defense and domestic spending that has been partially repealed each of the past four years but is scheduled to return in full for fiscal year 2018.

These policy changes would reduce taxes by $752 billion over a decade, increase non-interest spending by $1 trillion, and increase interest costs by $260 billion. The result would be $2 trillion higher debt, which would bring debt to 96 percent of GDP by 2027 as opposed to 89 percent. By 2047, along with a slight decrease in GDP growth, these policies would bring debt to 180 percent of GDP compared to 150 percent under current law.

| Provision | 2027 Debt Effect (Dollars) | 2027 Debt Effect (% of GDP) | 2047 Debt Effect (% of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Law | $24.9 trillion | 89% | 150% |

| Bonus Depreciation | $247 billion | 1% | 1% |

| Other Tax Extenders | $204 billion | 1% | 1% |

| Health Care Taxes | $311 billion | 1% | 7% |

| Sequester | $989 billion | 4% | 7% |

| Interest | $259 billion | 1% | 9% |

| Economic Growth | N/A | N/A | 5% |

| Current Policy | $26.9 trillion | 96% | 180% |

Source: Congressional Budget Office, CRFB calculations.

Building off this current policy scenario, policymakers could also change the long-term trajectory of certain categories to keep their closer to their historical average. In the past, CBO has constructed an Alternative Fiscal Scenario in which policymakers are assumed to freeze revenue at its post-tax cut 2027 level and increase non-health care, non-Social Security spending to its 20-year historical average of nearly 10 percent of GDP. Under this scenario, debt would rise to 225 percent of GDP by 2047, nearly three times higher than the current level.

Of course, there are many other ways that policymakers could increase deficits relative to current law. Potential unpaid-for tax cuts, infrastructure spending, or defense increases could also increase deficits and could significantly increase long-term debt depending on how lasting their impact is.

At the same time, policymakers could drastically improve the long-term outlook by making four major trust funds solvent that are projected to run out within the next 15 years. If they made trust funds for highways, Medicare, and Social Security solvent, debt would begin to stabilize after a decade or so and reach 84 percent of GDP by 2047 (as opposed to 150 percent under current law).

CBO's current law outlook already shows a bleak enough picture that will require significant deficit reduction to improve. Policymakers should certainly not make the problem more challenging by not offsetting the cost of maintaining any current policies they choose to keep or by passing new deficit-increasing legislation.