Five Easy Fixes that Won't Save Social Security

Tonight’s Presidential debate will include a discussion of debt and entitlements, which hopefully touches on the looming insolvency of the government’s largest program – Social Security.

Unfortunately, neither candidate has a plan to make Social Security solvent. To the extent they have suggested ideas to improve solvency, none represents a full solution – they either won’t be enough to solve the problem, or they would push the problem into the future or onto another part of the budget.

Below, we address some of these proposed solutions and their shortcomings, including:

- Ignore the Problem

- Eliminate Social Security Fraud

- Make the Rich Pay the Same as Everyone Else

- Grow the Economy

- Tax Passive Income

Proposed Fix #1: Ignore the Problem

The most popular Social Security plan in Washington, D.C. is the “do-nothing” plan. Yet Social Security’s trust fund will be depleted in less than 18 years, when today’s 50 year olds have just retired and today’s youngest retirees turn 80. At that point, all beneficiaries regardless of age or income will face a 21 percent benefit cut. That’s a $100,000 cut in lifetime benefits for a typical 50-year old and a $143,000 cut for a typical 30 year-old (See the cut you would face here).

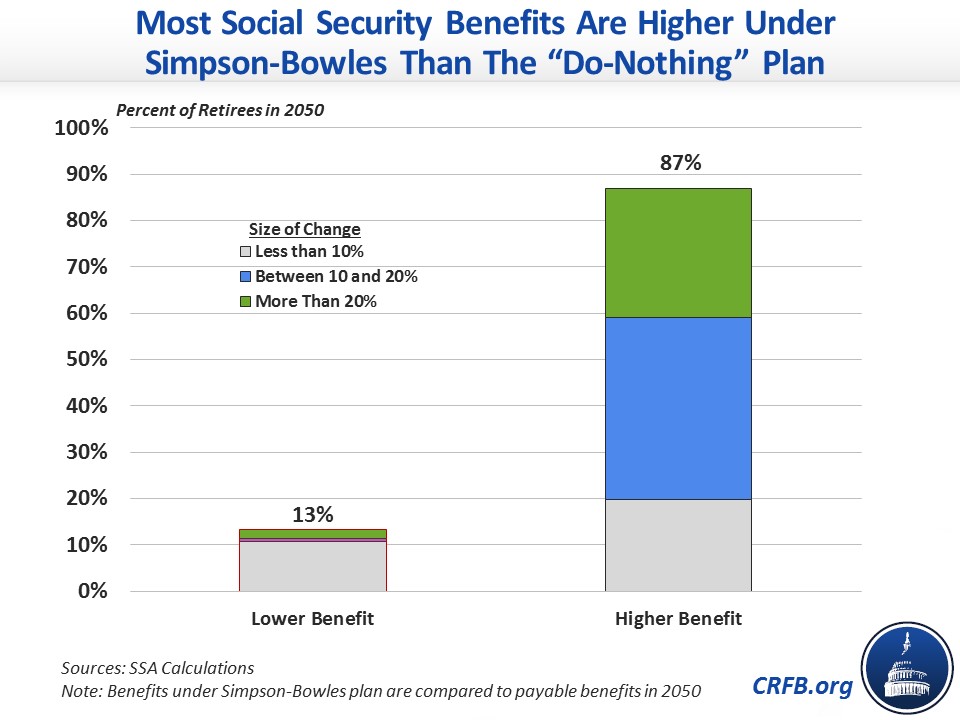

Doing nothing guarantees deep and immediate cuts to all beneficiaries in 2034, doubling the senior poverty rate and increasing retirement insecurity for the vast majority of seniors.

Nearly every reform plan proposed in recent years would result in higher benefits than this do-nothing approach. For example, in 2050 average benefits would be nearly 17 percent higher under the Simpson-Bowles plan than under the “do nothing plan,” with over 85 of the population receiving higher benefits and only a few very high earners facing significantly lower benefits.

And importantly, enacting such a plan today can give all workers a chance to plan and adjust.

Proposed Fix #2: Eliminate Social Security Fraud.

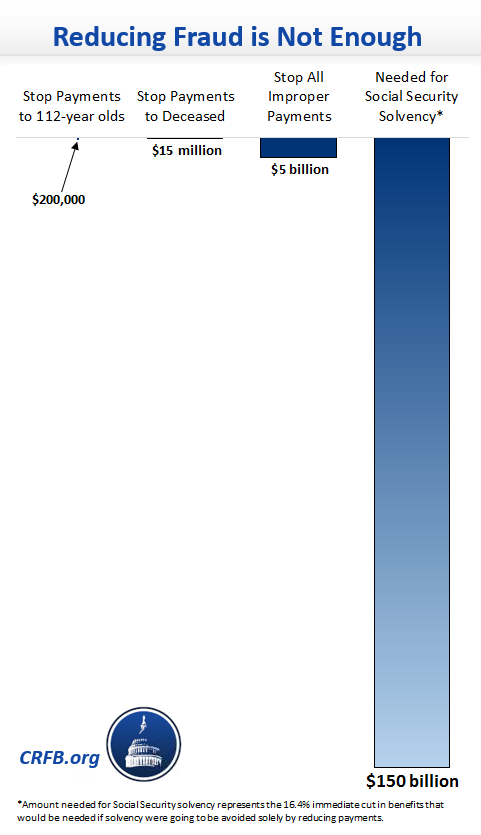

Certainly, some beneficiaries are fraudulently collecting Social Security retirement and disability benefits, and policymakers should do whatever they can to prevent this. However, even eliminating all fraud would not significantly improve the solvency of the program.

Simply put, there is not nearly enough waste, fraud, and abuse in the system to significantly impact its costs. The Social Security Administration estimates that improper payments – or payments made to the wrong person, for the wrong amount, or with insufficient documentation – total about $5 billion per year. By comparison, benefits would need to be cut by about $150 billion per year to make the program solvent.

This means that even assuming that the government could fully eliminate improper payments and do so with no additional spending on anti-fraud efforts – an impossible task – it would only close 3 percent of the program’s solvency gap and delay insolvency by four months. More realistic anti-fraud efforts would save only a fraction of that.

Proposed Fix #3: Make the Rich Pay the Same as Everyone Else.

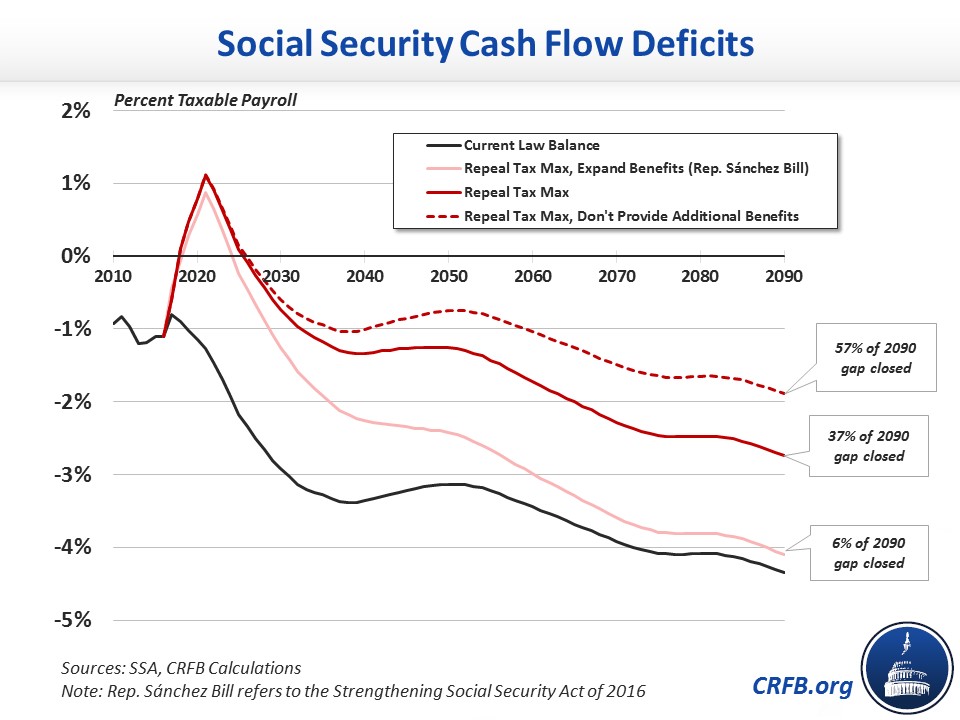

Currently, Social Security’s 12.4 percent payroll tax applies to a worker’s first $118,500 of wage income ($127,200 next year), and benefits are calculated based on that income. Though this “taxable maximum” is indexed to wage growth, it currently covers about 83 percent of all wages – meaning 17 percent of total wages are not subject to the Social Security payroll tax.

Certainly, increasing or eliminating income subject to the Social Security tax would improve the program’s finances, but it wouldn’t be enough to solve the problem – particularly on a structural basis.

Over 75 years, eliminating the taxable maximum – imposing a 12.4 percent tax increase on high earners (who currently face a top rate of about 44 percent) – would close more than two-thirds of Social Security’s solvency gap. This would be an important contribution to solvency, but importantly it would occur largely by creating surpluses in the near-term and crediting more benefits that would actually increase future spending. Cash deficits would return within 10 years and continue to grow over time. As a result, this change would close just over one-third of Social Security’s structural gap by 2090. In other words, a substantial portion of the fix defers the problem, but does not fix it.

To improve the structural impact of this change, policymakers could reduce the size of benefits which would be paid out as a result of this new higher income being subject to the tax. In the most extreme case, if policymakers severed the link between contributions above the current taxable maximum and benefits altogether, eliminating the taxable maximum could close over 85 percent of the program’s solvency gap and over 55 percent of its structural gap.

Unfortunately, many plans go in the other direction and use the temporary infusion of revenue to justify huge benefits expansions. For example, recent legislation proposed by Rep. Linda Sánchez eliminating the taxable maximum would ultimately spend nearly all of that new revenue on higher benefits and thus close just over 5 percent of Social Security’s structural gap.

Proposed Fix #4: Grow the Economy.

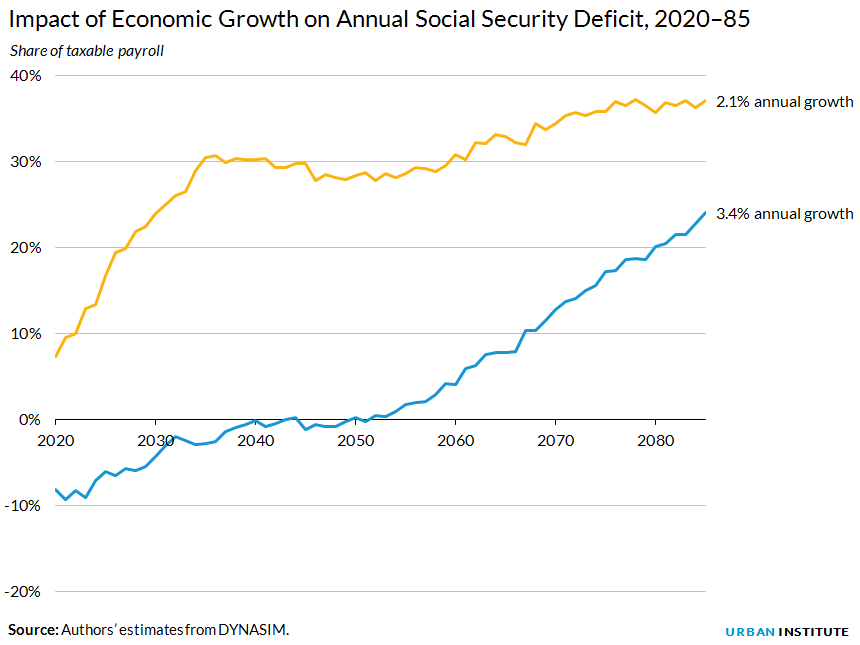

Faster economic growth would be great for Social Security, just as it would for the broader federal budget and for individual wages and income. But the level of growth needed to make Social Security solvent over the next 75 years is unachievable, and even if it could be achieved it would defer the program’s shortfalls rather than solve them.

In order to achieve 75-year solvency, real growth rates would likely need to average about 4 percent per year over the next 75 years – roughly double what is currently projected. As we’ve explained before, such levels of economic growth are not achievable given the current aging of the population. Even 3.5 percent economic growth – which is what the Trump campaign has claimed it can achieve – would require levels of productivity growth not achieved for any ten-year period in modern history, let alone for any 75-year period.

Moreover, because of the way Social Security is structured higher growth would in large part serve as a band-aid rather than a solution. Stronger economic growth means additional revenues come into the program; but because benefits are wage-indexed, it ultimately means more benefits paid out.

For example, the Urban Institute recently found that while increasing economic growth to 3.4 percent per year would push back Social Security’s insolvency date by about three decades, it would only close about one-third of the program’s structural gap, with cash surpluses ending around 2040 and rapid growth in the cost of benefits in excess of revenues continuing well into the future.

Importantly, those estimates assume the distribution of income both among earners and between wages and capital remains relatively stable over the long-run. If wages subject to the Social Security payroll tax continue to decline as a share of GDP – or if they don’t share in all the gains of economic growth – the positive impact of growth could be smaller.

Proposed Fix #5: Tax Passive Income.

Since eliminating the cap on wages subject to the Social Security tax wouldn’t be enough to make the program sustainably solvent, some have suggested also subjecting investment income to the payroll tax. For example, Senator Bernie Sanders recently proposed taxing capital gains, dividends, and interest income on earnings above $250,000 per year at 6.2 percent. This is on top of the 3.8 percent net investment income tax enacted in Obamacare.

Applying a 6.2 percent Social Security tax to investment income without crediting additional benefits would close about one-third of Social Security’s 75-year shortfall and a quarter of its structural gap in the 75th year. But it would do so, in large part, by effectively transferring revenue from the general budget into the Social Security trust fund.

Currently, high earners face a top capital gains tax rate of about 25 percent.* Because realizing capital gains is an entirely voluntary activity, evidence suggests increases in the tax rate dramatically reduce realization. The effect is so large, in fact, that official scoring agencies believe a top rate above roughly 30 percent would raise less total revenue than a top rate below it.

Yet a 6.2 percent capital gains increase would bring the top rate above 30 percent on its own – and well above 30 percent in concert with other proposals put forward by the Clinton campaign. This means that for every $1 raised from capital gains taxes for Social Security, nearly $1 will be lost from capital gains revenue going to the rest of the budget.

The effects of taxes on other passive income would be much smaller, though some revenue loss would still exist. This would greatly reduce the actual net revenue raised by taxing passive income; and if new benefits were paid on this additional income in order to preserve the link between benefits and revenue, it’s not clear the policy would be a net fiscal gain when full phased in.

The Real Fix: Negotiate A Comprehensive Reform Package.

There are no easy answers with Social Security. Aggressive fraud reduction can help a bit. Increasing the amount of income subject to the payroll tax can help much more. Broadening the payroll tax base can play an important role. And economic growth, to the extent it can be improved, would also help the program’s finances.

But ultimately, tough choices will need to be made. Policymakers will need to agree on a combination of tax and benefit changes that might include changes to the payroll tax max, rate, and base, as well as the program’s benefit formula, the retirement age, and other features of the program.

The technical aspects of such reform are not difficult. Our Social Security Reformer tool allows users to develop their own plans, and at least five existing Social Security reform plans provide a useful roadmap. The hard part is negotiating the agreement to fix the program. That will have to happen sooner rather than later in order to ensure the program can pay full benefits for current and future generations.

*this includes a 20 percent official rate, 3.8 percent for the net investment income tax, and an effective 1.2 percent rate from the Pease limitation on itemized deductions.