Trustee Blahous Says Time is Running Out to Fix Social Security

Charles Blahous, one of the public trustees for Medicare and Social Security, has released a Guide to the 2015 Social Security Trustees Report. The summary explains why Social Security's finances are unsustainable, citing rising beneficiary-to-worker ratios and growth in per-capita benefits, and urges policymakers to act now to fix the problem so that the required changes are not as sudden or burdensome.

Why are Social Security's Finances Unsustainable?

The summary outlines two underlying reasons for the unsustainability of Social Security's finances.

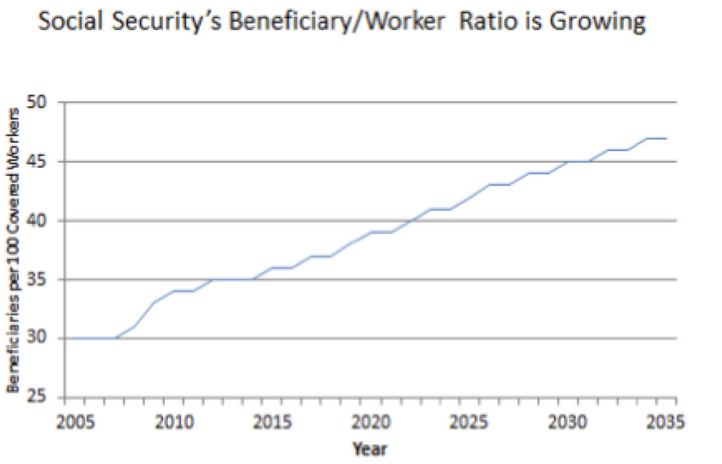

- The beneficiary population is forecast to grow faster than the worker population. This rise is driven by the decline in birth rates over the past 50 years and because people are living longer but retirement ages have not been increased commensurately.

- Per-capita benefits are scheduled to grow faster than inflation. This is because initial benefits grow with average wages, which tend to rise faster than inflation.

The Time to Act is Now

The summary also emphasizes the benefits of acting now to solve Social Security's financing problems, echoing the public trustees' statement that was released along with the 2015 report and in many previous CRFB blogs. In particular, he argues that to be effective "repairs must occur well in advance of the projected trust fund depletion date, and indeed the window of opportunity is already closing" and that "further inaction compounds the significant problems Social Security already faces."

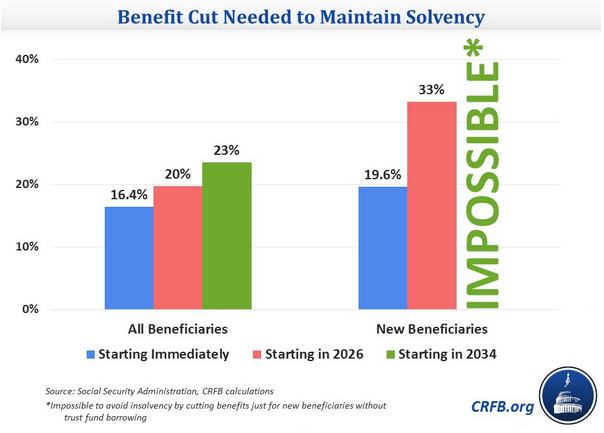

As an example, Blahous notes, as we have, that maintaining 75-year solvency would require a 19.6 percent cut to new beneficiaries' benefits immediately, but if policymakers wait until 2034, they would not be able to keep the trust fund solvent just by cutting new beneficiaries' benefits.

Blahous also argues that delaying efforts to fix this problem will likely lead to Social Security being "subsidized from other sources."

This could fundamentally alter Social Security, doing away with its historical basis as a benefit earned by worker contributions. For example, benefit programs paid from the government's general fund are largely financed by those who pay income tax, meaning that benefit amounts are not based on one’s personal tax contributions. Such “unearned” benefits tend to be much more subject to means-tests and sudden changes in eligibility rules, in a way that Social Security has historically escaped.

The Future is Already Here

Blahous points out that the impending exhaustion of the Disability Insurance (DI) trust fund is a great example of the downfall of waiting until the last moment to make changes. He notes that it is "virtually certain that any legislation to avert DI depletion will include at least a partial bailout of DI with funds heretofore allocated to another function," but that "whatever is done with respect to DI must not have the effect of contributing to further delays in the necessary corrections."

Policymakers must act quickly to put Social Security on a path toward solvency. As time goes on, it will be more difficult to secure the Social Security programs for current and future generations with thoughtful changes instead of abrupt benefit cuts or tax increases.