Summarizing the FY 2019 House Budget Resolution

House Budget Committee Chairman Steve Womack (R-AR) released his Chairman's Mark of the House FY 2019 budget resolution. The budget resolution calls for $8.1 trillion of deficit reduction (including rosy growth and other gimmicks), while including reconciliation instructions for committees to enact at least $302 billion over a decade. As we said in a recent press release, proposing a budget is an important first step in the budget process and reconciliation instructions are an important tool for deficit reduction, but much more would need to be done to truly fix the debt.

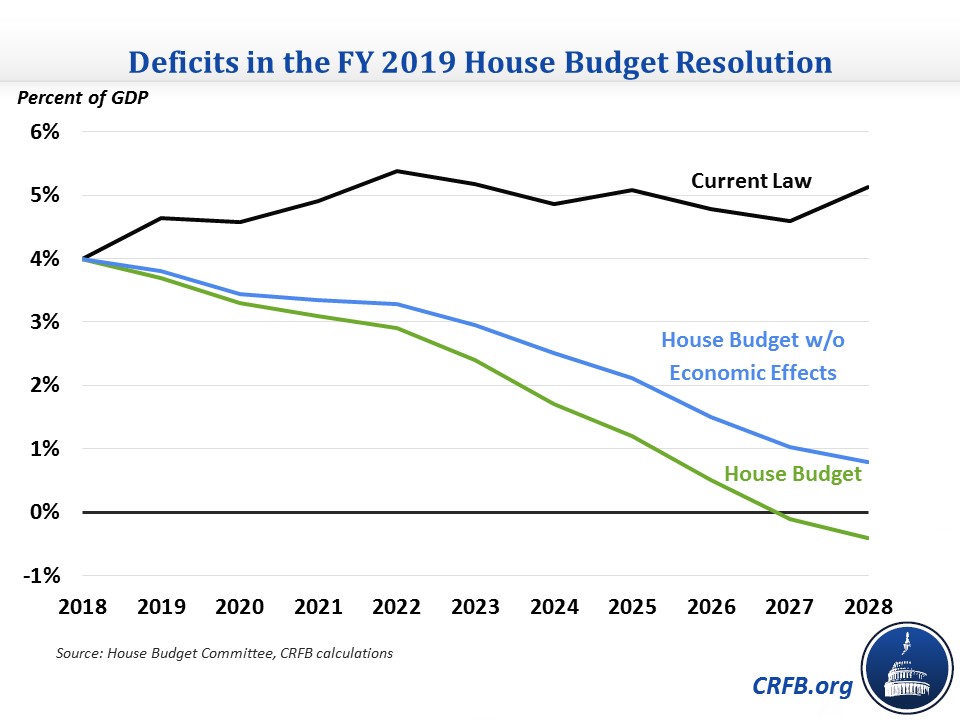

As written, the budget reaches balance by 2027. Deficits would fall steadily from $805 billion (4 percent of GDP) in 2018 to $146 billion (0.5 percent of GDP) by 2026 before producing a $142 billion (0.4 percent of GDP) surplus in 2028. The budget achieves these low deficits in part with extremely rosy economic assumptions. Removing these assumptions, the deficit would total $238 billion (0.8 percent of GDP) by 2028.

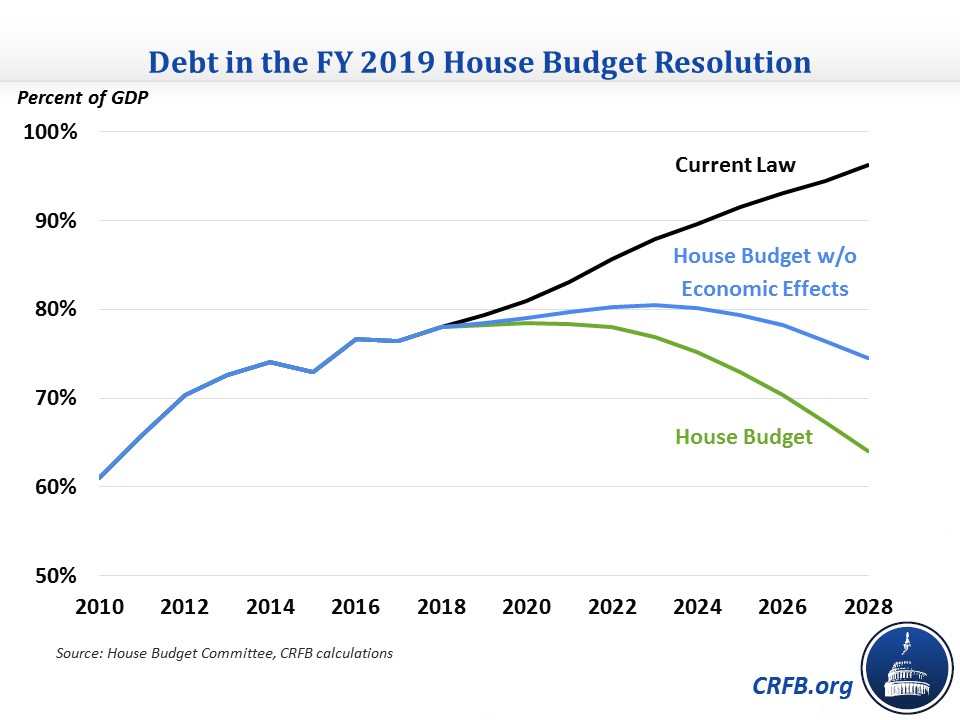

Declining deficits would lead debt to grow more slowly in dollar terms and shrink as a share of the economy. In nominal dollars, debt held by the public would rise from $15.5 trillion today to $20.6 trillion by 2028, compared to $28.7 trillion under current law. Relative to the economy, debt would fall from 78 percent of GDP in 2018 to 64 percent by 2028, in contrast to debt rising to 96 percent by 2028 under current law. Without rosy economic assumptions, debt would rise slightly in the near term then fall to about 75 percent of GDP ($22.2 trillion) by 2028.

The budget proposes $8.1 trillion of deficit reduction over the next decade relative to current law. $1.7 trillion (20 percent) of these savings would be from the feedback effects of rosy economic growth assumptions. The budget seems to assume average annual real GDP growth of 2.6 percent per year over ten years, compared to 1.8 percent in CBO's baseline. As a result, GDP would be nearly 8 percent larger by 2028.

Another $1.5 trillion (19 percent) of the savings comes from reductions to Medicaid and other health spending. These savings appear to come largely from Obamacare repeal but do not appear to reflect the full cost of any "replace" legislation. In addition, the budget calls for $537 billion of savings from Medicare, including from adopting premium support, using true out-of-pocket costs for measuring Medicare Part D's catastrophic cap, enacting tort reform, and improving program integrity.

The budget also includes $2.6 trillion of non-health mandatory savings over ten years. About $900 billion of these cuts come from income security, which the budget says it will meet in part by greater use of work requirements, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program reforms, and elimination of concurrent receipt of unemployment and disability insurance. Another $230 billion of cuts come from education and training programs, including by consolidating student loan programs and reducing Pell Grant awards.

$950 billion of the mandatory cuts in the budget are “undistributed,” and many of these are unspecified or unrealistic (for example, the budget calls for cutting improper payments by 50 percent).

Finally, the budget calls for $1.1 trillion of savings from discretionary spending, the net effect of $735 billion of defense increases, $340 billion of non-defense cuts, $160 billion of highway spending cuts, and $1.35 trillion of savings from assuming a drawdown of war and emergency spending. On the defense side, the budget resolution effectively extends and builds on the growth of the recent budget deal through 2021, then slows the growth of defense spending through 2028. On the non-defense side, the budget allows recent increases to disappear and the sequester to return as under current law in 2020, and freezes spending levels between 2022 and 2028.

The budget assumes no changes in revenue despite calls to extend the recent tax bill and change the tax code (directly and indirectly) as a result of Affordable Care Act "repeal and replace" legislation.

Savings in the FY 2019 House Budget Resolution

| Budget Category | 2019-2028 Savings |

|---|---|

| Medicaid and Other Health | $1,504 billion |

| Medicare (net) | $537 billion |

| Social Security | $4 billion |

| Other Mandatory | $2,578 billion |

| Discretionary and Highway | $1,120 billion |

| Revenue | $0 |

| Interest | $675 billion |

| Subtotal, Policy Savings | $6,454 billion |

| Assumed Economic Effect of Budget | $1,670 billion |

| Subtotal, Claimed Savings with Economic Effects | $8,124 billion |

Source: House Budget Committee.

Out of these total savings, the budget includes reconciliation instructions to 11 House Committees to achieve at least $302 billion of savings over ten years. Since reconciliation bills cannot be filibustered, they are the most actionable part of the budget resolution. The largest instructions, $150 billion, go to the Ways and Means Committee, and five other Committees (Judiciary, Oversight, Financial Services, Energy and Commerce, and Education and Workforce) have instructions ranging from $20 billion to $45 billion. The remaining five committees (Agriculture, Armed Services, Homeland Security, Natural Resources, and Veterans Affairs) each have between $1 billion and $5 billion of instructions, a nominal amount likely designed to give them flexibility in designing legislative reforms.

While these reconciliation instructions are small relative to the savings assumed in the budget, they are in some ways the most important and actionable part of the budget. At a minimum, policymakers should be able to agree to $300 billion of deficit reduction.

The FY 2019 House budget resolution calls for significant deficit reduction and includes reconciliation instructions to achieve a small portion of that deficit reduction. At the same time, the budget includes unrealistic savings and economic assumptions that make it look much better on paper than in reality. Still, we hope that the House budget will start the process towards achieving some actual deficit reduction this year.