The Student Loan Agreement: Not a Bad Deal for Students

Yesterday, CRFB praised the recent bipartisan agreement to enact a permanent fix for student loans instead of another temporary and costly solution. The agreement would reduce interest rates for all borrowers in 2013 and then permanently peg future rates to those of government bonds in a way that will not add to ten-year budget deficits. The deal would be a permanent and fiscally responsible solution -- not something we see everyday.

Some critics, however, are unhappy with the deal, arguing that it will ultimately place a high burden on students. Many have argued for simply continuing the 3.4 percent interest rate under current law. In our view, the solution put forward in the Senate is much better.

As a starting point, it is important to understand what the bill would do for new borrowers. For 2013, all students will see reductions in their loan rates compared to what is currently in place -- more than a 40 percent reduction for undergraduate and 20 percent reduction for everyone else. Compared to last year, subsidized Stafford loans will see a very modest rate increase (from 3.4 to 3.85) while other loan rates will fall quite dramatically (from 6.8 to 3.85 for unsubsidized Stafford loans, as an example).

It is true that nominal student loan interest rates will increase over time, as economy-wide interest rates recover. By our calculations, undergraduate loans in 2023 will offer an interest rate of roughly 7.25 percent (though that number could be lower if a deficit-reduction plan were enacted). Importantly, though, the fact that student loan interest rates adjust over time is a feature of the deal, not a flaw.

Under prior law, nominal interest rates stayed fixed regardless of interest rates, inflation rates, or broader economic conditions. Meanwhile, returns on bank accounts and interest rates on mortgages and all other loans adjust as the economy does. Critics see the fixed rate as protection against high interest rates in the rest of the economy, but they forget that it is also punishment against low rates -- a situation that the country faces today. Indeed, this fixed rate is the reason for the $10 to $40 billion profit some have criticized the government for making off of student loans in 2013. This profit for the government is the result of fixed nominal student loan rates contrasted to constantly moving government bond rates.

The right way to measure how much the government is subsidizing borrowers (outside of non-rate subsidies) is not by where nominal rates are, but how they compare to the rate at which the government is borrowing. Of course, student loans will necessarily have higher rates than government bonds to finance administrative costs, collections, and the risk of default, forgiveness, and delinquency.

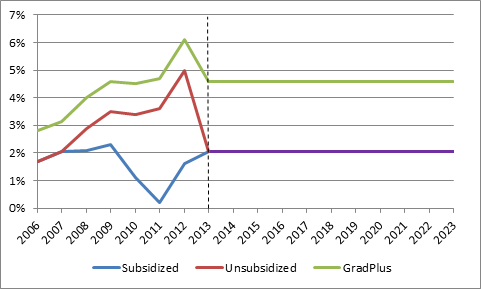

Over the last few years, the subsidy has swung wildly. The bipartisan legislation that will be considered by the Senate would very slightly reduce the subsidy for subsidized Stafford loans, and would increase the subsidy quite significantly for all other types of loans. After that, it would hold the subsidy constant by fixing interest rates to the ten year bond -- with downside risk to students born entirely by the government through nominal caps on how high the interest rates could go.

Difference Between Student Loan Rates and Ten-Year Treasuries

Source: CRFB

But what about the 3.4 percent rate? It's important to understand that this rate was arbitrary, temporary, and never really affordable. Jason Delisle at the New American Foundation offers a useful history of the 3.4 percent rate. While House Democrats in 2006 campaigned on cutting student loan rates in half, they found after taking the House that doing so would be quite costly -- $133 billion over ten years. Instead, they reduced rates on only a small subset of loans (subsidized Stafford loans), did so gradually over five years, and allowed the reduction to expire in the sixth year. In total, the 3.4 percent rate stayed in effect for only two years. Due to the coincidentally low interest rate environment in the rest of the economy, this low interest rate ended up making some sense. Continuing it over the long-run, however, would be unsustainable.

The Senate agreement on student loans shows that policymakers can come together on a bipartisan basis to find lasting solutions to our problems. It would have been easy to kick the can down the road for another year. Instead, they found a fiscally responsible solution that reduces costs for all borrowers in 2013 and then locks in place the effective subsidy in order to protect future taxpayers from excessive liability. Now that a solution has been identified, it's time for policymakers to put this issue behind us and transfer some of the bipartisan spirit generated on this agreement for lingering challenges still facing the budget.