Restoring Highway Solvency by Reducing Spending

We released a new paper, Trust or Bust: Fixing the Highway Trust Fund, which showed the Highway Trust Fund (HTF) faces a $170 billion shortfall over the next decade and provided numerous options to close that shortfall. In a previous blog, we explored options for doing that by increasing revenue from sources that are currently dedicated to the HTF. Another strategy to close the gap is to reduce the amount the federal government spends on highway programs going forward. In the table below, we describe a number of options to do just that.

| Options To Reduce Highway Spending | ||||

| Policy | Ten-year savings | Percent of Shortfall Closed | ||

| 4-year | 6-year | 10-year | ||

| Freeze spending at 2014 levels for ten years | $40 billion | 8% | 14% | 25% |

| Freeze spending at 2014 levels for two years | $15 billion | 7% | 8% | 9% |

| Reduce spending to 2008 levels | $85 billion | 45% | 50% | 50% |

| Reduce spending by 35 percent | $170 billion | 75% | 90% | 100% |

| Eliminate new commitments for one year | $55 billion | 70% | 50% | 30% |

| Eliminate new commitments for two years | $105 billion | 140% | 100% | 60% |

| Eliminate funding for capital investment grants | $15 billion | 7% | 9% | 10% |

| Reduce Highway Safety Improvement funding to 2012 levels | $10 billion | 6% | 6% | 7% |

| Reduce CMAQ program by 50% | $10 billion | 5% | 6% | 6% |

| Eliminate funding for alternative transportation | $10 billion | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| Return TIFIA program funding to 2012 levels | $10 billion | 4% | 4% | 5% |

| Repeal Davis-Bacon Act for highway projects | $5 billion | 3% | 4% | 4% |

| Eliminate funding for federal lands transportation | $5 billion | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Improve grants to focus on high-priority spending | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Leverage state, local, and private spending | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Sources: CBO, Federal Highway Administration, CRFB calculations

All numbers are rounded and calculated very roughly by CRFB based on data from a variety of sources.

Percentages represent average effect over the time period and do not address timing issues.

Reduce Future Obligation Limitations

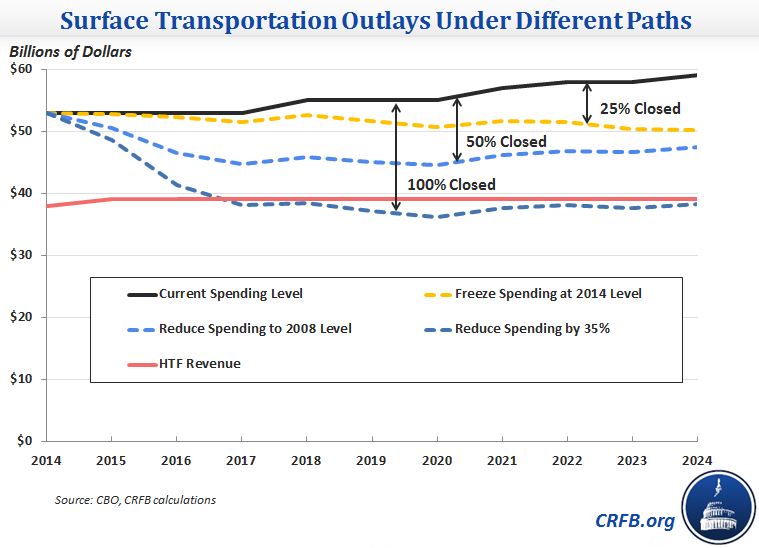

The Congressional Budget Office baseline assumes that highway spending will continue to grow with inflation over time, meaning funds allocated for new projects will grow from $53 billion in 2014 to $65 billion by 2024, and total nearly $600 billion over the next decade. One option to reduce spending is to simply reduce these future top line levels.

A 35 percent reduction in new obligations, combined with temporary borrowing authority, would keep the HTF fully solvent over the next decade. Importantly, this would represent a sizeable cut in surface transportation spending, although states would likely pick up some of the difference.

A more modest approach would be to slow nominal growth in highway spending. For example, a two-year freeze in spending levels would close 10 percent of the gap, while a ten-year freeze would close one-quarter. Reducing spending to 2008 levels and allowing it to grow with inflation thereafter would close 50 percent of the gap.

Under any of these approaches, specific decisions would need to be made on how to spend within these topline levels. Also note that getting the requisite $170 billion of outlay cuts would require a greater amount of contract authority cuts, since some of the contract authority that is cut, particularly in later years, would not have actually been spent out until after 2024.

Temporarily Halt New Projects

Rather than modestly reducing spending in all future years, policymakers could choose to simply halt new projects for a period of time. For example, a one-year hiatus would extend the life of the HTF until 2017 and close one-third of the ten-year gap. A two-year hiatus would extend the life of the HTF until 2021 and close 60 percent of the ten-year imbalance. Policymakers could also partially reduce new project funding. Temporarily reducing new project funding by 50 percent over the next two years would close about one-third of the ten-year gap.

Importantly, these savings assume that spending levels after the hiatus are not increased to make up for the lack of new spending during the hiatus.

Reduce the Cost of Projects

It is also possible for the government to reduce the total cost of highway spending without reducing the number of projects undertaken. One way to do so would be to repeal or reform the Davis-Bacon Act, which requires contractors for federally funded construction projects to pay workers the locally prevailing wage. According to the Congressional Budget Office, reforming or repealing this policy could save $2-$6 billion over ten years from highway projects alone, with additional savings coming from other construction projects.

There may be other ways to reduce costs, including a more competitive bidding process, more restrictions on contracts, limits on how much the government is willing to pay for certain goods, more requirements for states, or other tools.

Repeal or Reduce Certain Areas of Highway Spending

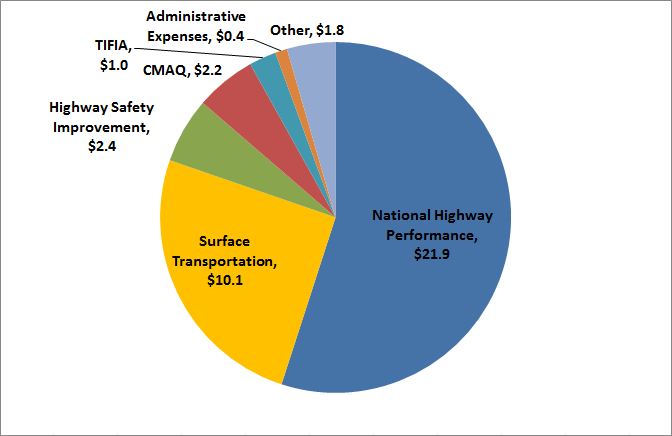

Rather than making top-level decisions, policymakers could also reduce or eliminate spending on certain areas within the HTF. Eliminating spending on the Transportation Alternatives Program, which provides funding for things such as bicycle facilities, hiking trails, and safe routes for walking or biking to school, would save about $10 billion over ten years. Eliminating funding for capital investment grants for rail, buses, and ferries would save about $15 billion over ten years. Reducing funding for the Transportation Infrastructure Financing and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program, which makes loans to significant infrastructure projects, to 2012 levels (rolling back the expansion in the most recent highway bill) would save $10 billion, as would halving funding for the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) program and the Highway Safety Improvement program (bringing spending back to 2012 levels for the latter). Removing funding for the Federal Lands Transportation program and requiring it to be made up elsewhere would save just under $5 billion.

Distribution of Highway Spending in FY 2014 (billions)

Source: Federal Highway Administration

Improve Grant Formulas

Another way to allow lawmakers to reduce new obligations is to invest more wisely in infrastructure spending by focusing on high-priority areas. In a 2009 report, the National Transportation Policy Project (NTPP) at the Bipartisan Policy Center made a number of recommendations for surface transportation spending, including changing allocation formulas to reward states for meeting certain goals. It built its criteria for establishing priorities around five areas: economic growth, national connectivity, metropolitan accessibility, energy and the environment, and safety. In addition to eliminating low-priority programs, the NTPP recommended consolidating programs and designing them with formulas to reward effective performance. Obviously, lawmakers could take any number of design approaches.

Leverage State, Local, or Private spending

To reduce spending from the HTF, lawmakers could leverage spending from other sources at a lesser cost to the federal government. They could do this directly with highway spending by using public-private partnerships or limiting the share of federal financing for state and local projects. They could also encourage states to use credit (possibly with federal assistance from TIFIA) to finance large projects and pay back the loans with tolls or other dedicated revenue. Alternatively, the federal government could use tools to leverage private infrastructure investment such as a national infrastructure bank or something like the Build America Bonds that were in effect for 2009 and 2010 (or President Obama's similar proposal, America Fast Forward bonds). Any of these options would reduce the cost of surface transportation to the federal government, but they could maintain or even increase the overall level of spending.

*****

As we show, there are numerous ways to reduce federal highway spending. These approaches, either on their own or in combination with new revenues or funding sources, could fully fix the HTF for the next decade and beyond. To be sure, policymakers may not want to reduce highway spending. For example, the president's budget would actually increase new obligations by $81 billion over CBO's baseline for the next four years. However, even if policymakers do choose to increase highway spending, they should allocate that spending in the most efficient and cost-effective way possible. Moreover, the greater highway spending is, the more funds must be raised to ensure the HTF remains solvent. In our recent paper, we discussed a number of options that increase revenues from new and existing funding sources. We will continue writing on these issues in the coming days.