Reforming the Debt Ceiling

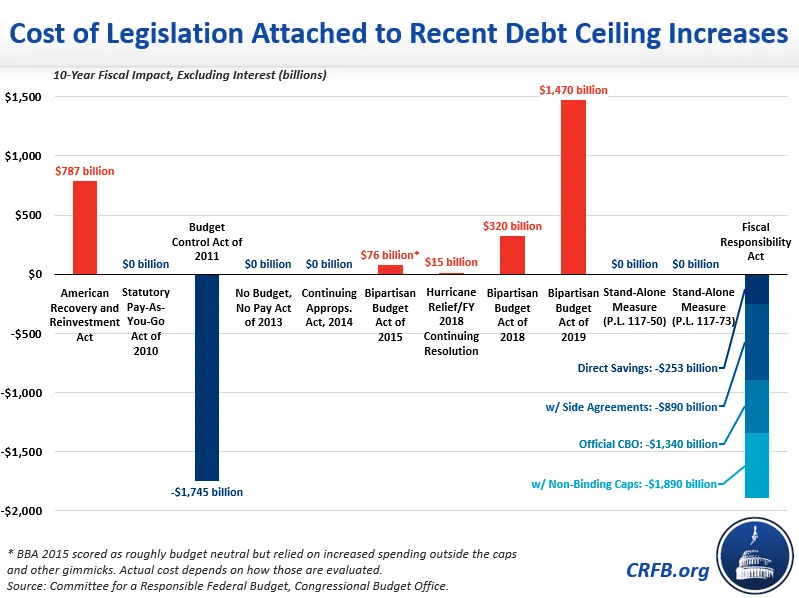

The debt ceiling was reinstated on January 2, 2025. Lawmakers should lift it as soon as possible rather than relying on extraordinary measures and waiting until the last minute. Some have suggested eliminating or reforming the debt ceiling to avoid the risk of default. While avoiding default is absolutely necessary, it is noteworthy that the debt ceiling is one of the federal government’s few fiscal constraints, and it has been accompanied by fiscal improvements many times in the past.

We recommend:

- Lawmakers lift the debt ceiling as soon as possible, ideally including measures that reduce the debt and absolutely not including measures that make it worse.

- Any debt ceiling reforms be structured to encourage fiscal improvements while avoiding the risk of default.

Select Past Debt Ceiling Increases and Their Fiscal Attachments

| Title of Bill/Package, Year | Debt Ceiling Change | Notable Attachments and Context |

|---|---|---|

| Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act, 1985 | Increased $175B | Set targets for balanced budget, enforced by sequestration |

| Gramm-Rudman-Hollings II, 1987 | Increased to $2.8T | Built on GRH with additional deficit reduction requirements, enforced by sequestration |

| Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, 1990 | Increased $915B | Nearly $500 B in deficit reduction over five years, statutory PAYGO, and spending caps |

| Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, 1993 | Increased $600B | Reduced deficits by ~$500 B in five years, extended 1990 spending caps, raised taxes on high earners |

| Contract with America Advancement Act, 1996 | Increased $600B | Passed with POTUS line-item veto power to strike certain narrow programs and tax benefits |

| Balanced Budget Act, 1997 | Increased $450B | Put in place ~$125 B of net deficit reduction over five years and $425 B over ten years |

| Statutory PAYGO Act, 2010 | Increased $1.9T | Reinstated statutory PAYGO, informally led to establishment of Simpson-Bowles Fiscal Commission |

| Budget Control Act (BCA), 2011 | Let POTUS increase $2.1T in tranches, subject to Congressional disapproval | $917 B in deficit reduction over ten years with interest, mostly with discretionary spending caps, established the “Super Committee” to save at least $1.2 T with interest |

| No Budget, No Pay Act, 2013 | Effectively suspended to 5/19/13 | Required each chamber to pass a budget, enforced by withholding compensation of Members of Congress |

| Default Prevention Act, 2013 | Suspended to 2/7/14 | Set up a bicameral budget conference to reconcile budgets for FY 2014; ended a government shutdown |

| Bipartisan Budget Act, 2015 | Suspended to 3/15/17 | Cost ~$76 B with interest removing gimmicks, increased BCA caps for 2016 and 2017 |

| Bipartisan Budget Act, 2018 | Suspended to 3/1/19 | Cost $420 B with interest, increased BCA caps for 2018 and 2019 |

| Bipartisan Budget Act, 2019 | Suspended to 7/31/21 | Cost $1.7 T ($360 B directly) with interest, by increasing caps for 2020 and 2021 (increases were built into baseline) |

| Fiscal Responsibility Act, 2023 | Suspended to 1/1/25 | $1.5 T in deficit reduction with interest over ten years, mostly through discretionary spending caps |

Options to Reform the Debt Ceiling

Link changes in the debt limit to achieving responsible fiscal targets

1. Grant Presidential authority to increase the debt limit if fiscal targets are met – Congress could set specific fiscal targets and grant the President the authority to raise the debt limit when necessary, so long as the targets are met. The targets could use a fiscal metric such as debt-to-GDP ratio being below a specific level or projected to reach that threshold at some point in the future under current law.

2. Grant Presidential authority to increase the debt limit if accompanied by a plan to put debt on a declining path as a share of GDP – Policymakers could grant the President the authority to raise the debt limit by the amount needed to accommodate the President’s budget as long as those policies would put debt-to-GDP on a downward path. Congress would retain the right to disapprove of that increase and would need to act separately if debt increased more than projected in the President’s budget. In other words, lawmakers would need to enact policies at least as fiscally responsible as the President’s budget to avoid a debt ceiling vote. Unforeseen budget or economic circumstances could also necessitate a debt limit vote.

3. Suspend the debt limit automatically if fiscal targets are met – Lawmakers could set fiscal targets and create a mechanism whereby the debt ceiling is automatically suspended contingent on enactment of policies that would meet those targets. The targets could be fiscal metrics such as current debt levels as a share of GDP, future projected debt, solvency of entitlement trust funds, total unfunded liabilities, or other measures of fiscal sustainability.

Incorporate the debt limit into Congress’s fiscal decision-making

4. Automatically increase the debt limit upon passage of budget resolution – Policymakers could adjust the budget process so that when the House and Senate pass a concurrent budget resolution, legislation providing for a debt limit increase automatically goes to the President for signature. In the past the House had such a rule, named after former Representative Richard Gephardt (D-MO), where the debt limit increase legislation was deemed to have passed the House upon passage of a budget resolution conference report. The Senate has not had such a rule in place.

5. Require reconciliation instructions to increase the debt limit to accommodate debt levels in the budget resolution – Currently, Congress can raise the debt limit via budget reconciliation, though that process is optional; this change would require those instructions in every budget resolution.

6. Require legislation with significant net costs to include an increase in the debt limit –Congress could require each piece of legislation that would increase net borrowing to also increase the debt limit. Lawmakers could set the standard to apply against the current law baseline or the deficit levels specified in a concurrent budget resolution. In other words, lawmakers would face a hurdle in violating their budget or increasing debt relative to current law.

Apply the debt limit to more economically meaningful measures

7. Subject debt held by the public instead of gross debt to the debt limit – The debt limit currently applies to the gross national debt, which includes debt the federal government owes itself. Instead, Congress could change the debt limit to apply to the more economically meaningful measure of debt, debt held by the public.

8. Index the debt limit to GDP growth, effectively capping debt-to-GDP – The debt limit currently applies to a fixed dollar amount. Instead, Congress could apply the debt limit to debt-to-GDP, which would effectively index debt growth and cap the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Replace the debt limit with a limit on future obligations

9. Apply the debt limit to future liabilities and unfunded obligations – The current debt limit applies to debt incurred from past liabilities. Congress could shift this to apply to future or unfunded liabilities, which could be achieved by capping the net liabilities of the federal government and net social insurance liabilities in excess of revenues estimated in the Treasury Department’s Financial Report of the United States Government.

10. Replace the debt limit with a “debt cap” – The debt limit is currently enforced by prohibiting any further borrowing. Congress could replace this with requirements to reduce future borrowing. One approach to do this would be to replace the statutory debt limit with a “debt cap” that requires Congress and the President to enact policies to ensure the debt-to-GDP ratio is within specified targets, enforced by automatic spending cuts and revenue increases if Congress and the President fail to act. The debt cap could apply to the upcoming fiscal year, or to a rolling five-year period.

Note: For more details, see our full paper.

Conclusion

As lawmakers continue discussions of changes to the debt limit, they should keep in mind any change should maintain the goal of forcing a conversation about our fiscal outlook among policymakers while reducing the potential harm from default. The debt limit is a flawed tool, but at times, it has served as an important reminder to assess the nation’s budget path and has been paired with the most significant laws to reduce the deficit in recent history.