Policymakers Should Reform Student Loan Programs

Lawmakers will need offsets to keep year-end legislation from substantially worsening the debt, and one area we've suggested in our Mini-Bargain and elsewhere is the Federal Direct Student Loan Program. President Obama and President Trump both proposed major savings from reforming the in-school interest subsidy, income-driven repayment plans, and the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, and a recent bill from the House Education and Workforce Committee includes many of President Trump's proposals.

Each of these policies is intended to help students finance their education, but accessing them means navigating a web of different programs and paperwork, and funds can end up going those who need the least help. The in-school interest subsidy is an ineffective, poorly targeted, and expensive policy. Income-driven repayment plans could be streamlined and modified to better help borrowers in distress rather than graduate school borrowers with large debts but promising careers. Public Service Loan Forgiveness currently benefits a much larger and better-off group of borrowers than was originally intended. Reforms to each could improve simplicity and progressivity while also generating substantial savings, some of which could be put towards more effective and better-targeted programs like Pell Grants or counseling services.

In-School Interest Subsidy

Most of the federal government’s direct loans to student borrowers are Stafford loans, which are available in both "unsubsidized" and "subsidized" varieties (though both actually receive a federal subsidy). Unsubsidized Stafford loans are open to all undergraduate and graduate borrowers regardless of income at terms that are generally much more favorable than private loans. Subsidized Stafford loans carry an extra benefit in that interest on the loan does not accrue while the borrower is in school.

Subsidized loans are limited to undergraduate students who meet certain eligibility requirements, but these requirements are not based strictly on income, and students from higher-income families attending expensive colleges are often able receive the in-school interest subsidy; about 18 percent of subsidized loans for dependent students went to borrowers with family incomes above $100,000. The subsidy is also an ineffective tool for helping low-income individuals pay for college, as the benefits only appear to borrowers after they have finished school, and even then, they are delivered in a nontransparent way.

President Obama's fiscal year (FY) 2012 budget recommended eliminating the in-school interest subsidy for graduate students, which was achieved in the Budget Control Act of 2011. President Trump's FY 2018 budget and the House Ed & Workforce bill would both eliminate the subsidy for undergraduate debt as well, saving $23 billion over ten years according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Another option would be to limit the subsidy to undergraduates eligible for Pell grants, which would save about $8 billion, or to limit the period interest does not accrue strictly to time spent as an undergraduate.

Income-Driven Repayment

The Department of Education offers a variety of repayment plans, with the standard plan requiring the borrower to make 120 fixed monthly payments over 10 years to fully repay the loan and any accrued interest. Borrowers can also opt for one of several different income-driven repayment (IDR) plans, where monthly payments are set at a specified percentage of their discretionary income (most commonly 10 percent) for a certain repayment period (usually 20 years), after which the outstanding balance is forgiven.

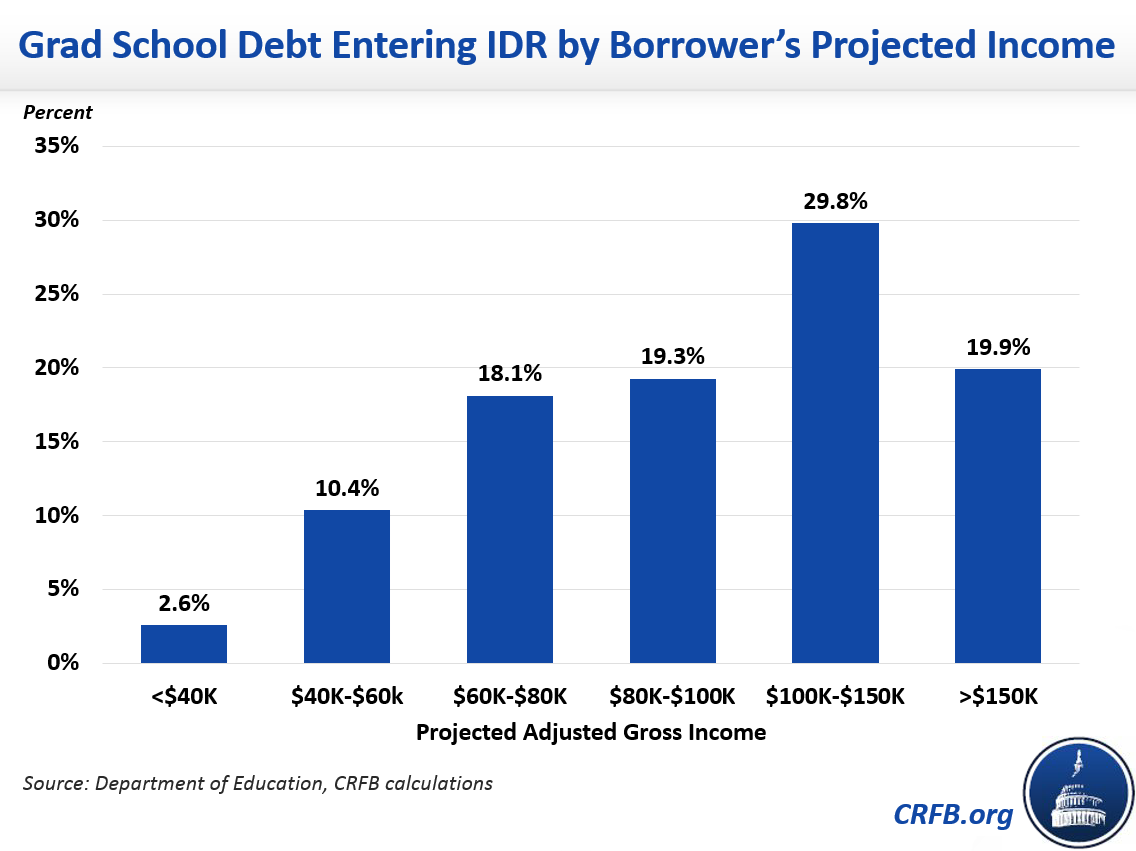

IDR plans are generally meant to help those who run into unexpected difficulties in paying off student loans, but they can unintentionally benefit individuals who choose to enroll in expensive colleges, opt for certain careers, or spend more years in school to earn advanced degrees. The biggest beneficiaries of IDR are those borrowing to pay for graduate and professional school, who usually borrow much larger amounts than undergraduate borrowers but in turn earn higher incomes. About 65 percent of debt entering IDR repayment in 2016 was held by graduate students, and the Department of Education estimates nearly 50 percent of graduate school debt in IDR was held by borrowers with projected incomes of more than $100,000 per year. In addition, monthly IDR plan payments are capped at whatever the borrower would be paying under a standard 10-year plan, which favors high-income borrowers and can cause some borrowers who would otherwise pay off their debt to receive loan forgiveness.

Presidents Obama and Trump have each proposed moving to a single IDR plan that eliminates the standard repayment cap and increases the repayment period for people who borrow to pay for graduate school, though President Trump’s proposal is more aggressive. President Trump’s IDR plan would set the monthly payment at 12.5 percent of discretionary income. The repayment period would be set at 15 years undergraduate debt and 30 years for graduate school debt, providing quicker debt relief to undergraduate borrowers while requiring graduate borrowers to make 15 years of additional payments before their loans are forgiven. CBO estimates these changes would save roughly $53 billion over the budget window (this estimate includes large interactive effects with other proposals).

President Obama's IDR proposal was similar, only the monthly payment would be set to 10 percent and the repayment period would be 20 years for undergraduates and 25 years for graduate school borrowers, saving approximately $17 billion. CBO has separately estimated that increasing the repayment period for graduate students to 25 years would save $12 billion, while eliminating the standard repayment cap would save about $5 billion (interactions would cause combined savings to be lower than the sum of the two options).

Public Service Loan Forgiveness

IDR borrowers can also qualify for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), which provides debt forgiveness after just 10 years of monthly payments if the borrower is employed full time in public service. Public service is defined very broadly, and includes any job at any level or government or at a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, which the Government Accountability Office has estimated covers about one-quarter of all jobs.

Like IDR, PSLF is especially generous to doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who can potentially have large unpaid graduate school debts forgiven after 10 years, even when they have high incomes that would allow them to eventually pay off their remaining debt with relatively little trouble. The result is a major incentive to borrow more for graduate school, and nearly 30 percent of PSLF enrollees carry more than $100,000 in federal student loan debt. And unlike IDR loan forgiveness, PSLF is tax-free, which delivers the largest benefit to higher-income borrowers in higher tax brackets.

President Obama proposed capping PSLF at $57,500 (the maximum that an independent undergraduate can borrow in federal loans) and shifting any remaining balance to an IDR plan, which would save roughly $7 billion over a decade. President Trump and the House bill would eliminate PSLF outright for new borrowers, saving $24 billion.

| Policy | Current Law | Trump FY18 | Obama FY17 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income-Driven Repayment Plans | Five IDR Plans (IBR, Original IBR, PAYE, REPAYE, and ICR) | Consolidated into a single plan | Consolidated into a single plan |

| Loan Payment Cap as a % of Discretionary Income | Varies by plan: 10% (PAYE, REPAYE, IBR); 15% (Original IBR); 20% (ICR) | 12.5% | 10% |

| Standard Repayment Cap | Repayment capped regardless of income | Eliminated | Eliminated |

| Forgiveness for Undergraduate Debt | After 20 years (PAYE, REPAYE, IBR); After 25 Years (Original IBR, ICR) | After 15 years | After 20 years |

| Forgiveness for Graduate School Debt | After 20 years (PAYE, REPAYE, IBR); After 25 Years (Original IBR, ICR) | After 30 years | After 25 years |

| Subtotal IDR Savings | $53 billion* | ~$17 billion | |

| In-School Interest Subsidy | Subsidized loans do not accrue interest during or immediately after school | Eliminated (savings: $23 billion) |

N/A (previously proposed eliminating subsidy for graduate school debt) |

| Public Service Loan Forgiveness | Debt forgiveness after 10 years of public service | Eliminated for new borrowers (savings: $24 billion) |

Capped at $57,500 (savings: $7 billion) |

| Other Policies | End account maintenance fee payments to guaranty agencies (savings: $1 billion) |

Reform and expand Perkins loan program (savings: $3 billion) |

|

| Total Savings | $100 billion | $26 billion |

Sources: Department of Education, Congressional Budget Office, Brookings Institution.

* = Includes substantial interactive effects with eliminating PSLF.

Note: Obama scores use the 2017-2026 budget window; actual savings would likely be slightly higher. All savings could be lower if scored using fair-value methods.

Smart changes to student loan programs could reduce incentives to take on additional debt while also helping the federal government manage its own debt problem. Policymakers could pursue one of the ambitious overhauls outlined by Presidents Trump and Obama or take a more incremental approach to improving and simplifying these programs. Either way, there are many options available for reforming federal student loans to better target assistance to those who need it and eliminate windfalls to those who do not.