Over Half of States Ending Federal Unemployment Benefits Early

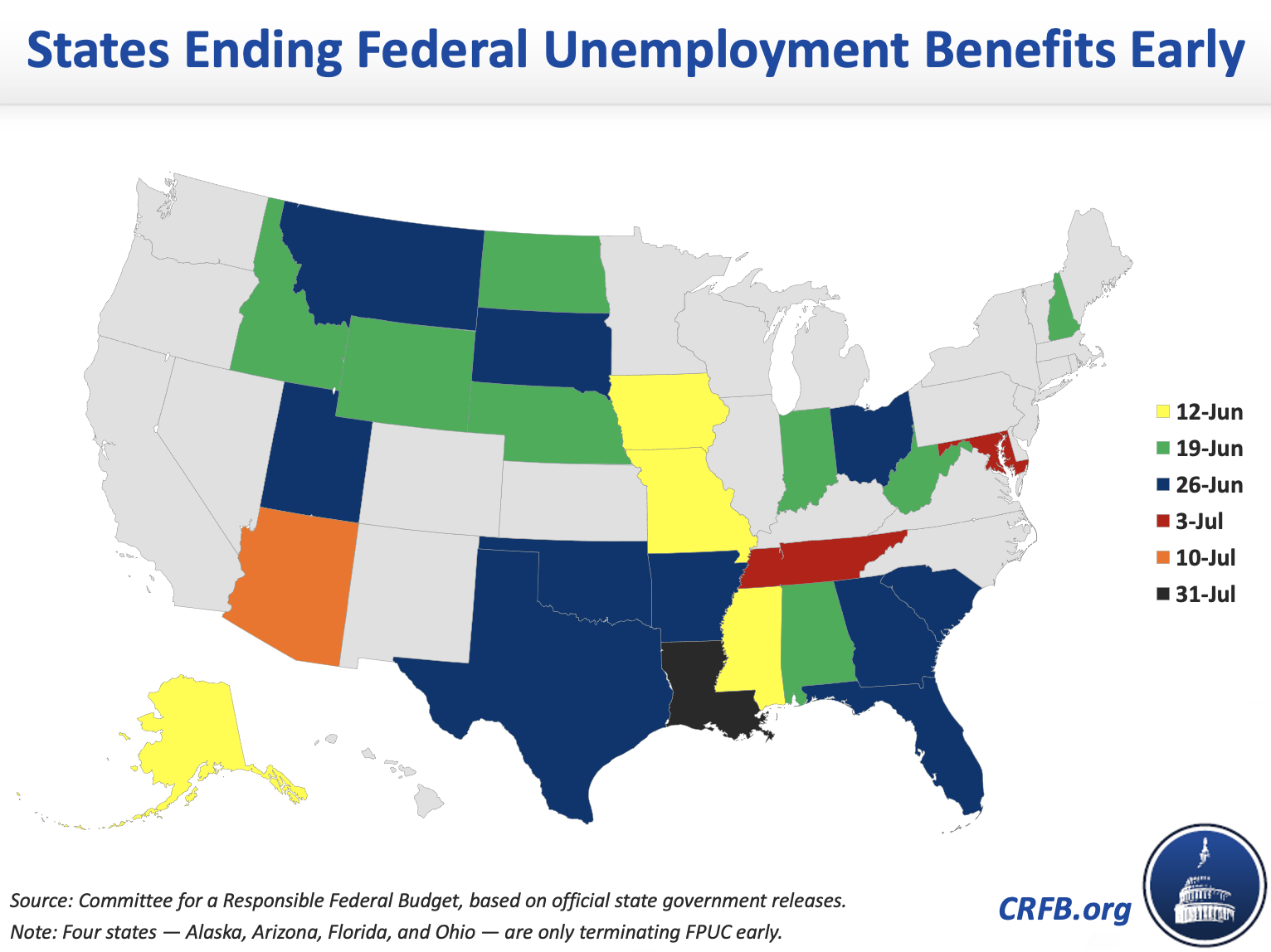

Twenty-six states have announced that they are ending the expanded federal unemployment benefits in the American Rescue Plan prior to their technical expiration date in early September. Twelve states have already terminated expanded benefits.1

The Congressional Budget Office originally estimated that combined spending on the three major emergency federal unemployment programs in the American Rescue Plan would total $206 billion. However, even before accounting for early state terminations, we estimate total spending on these programs will be about 20 percent lower than CBO’s estimate, due to lower-than-expected spending thus far. After accounting for early state terminations, we estimate the total deficit impact for these three programs will be a further 10 percent lower, or 27 percent lower than originally forecast — around $150 billion versus $206 billion.

The American Rescue Plan extended or reauthorized several federally-funded extensions and expansions of state unemployment insurance (UI) programs, including Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC), Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), and Federal Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC).2 In its current iteration, FPUC provides an additional $300 per-week for unemployed persons. PUA provides unemployment benefits to those not typically eligible for UI benefits, including gig economy and self-employed workers, and PEUC provides an additional 29 weeks of benefits for those who have exhausted regular state and federal UI.

All three benefits are payable through September 4 under the bill. However, over recent weeks, 26 states have decided to end federal UI benefits between two to three months earlier than their official September 4 deadline.3

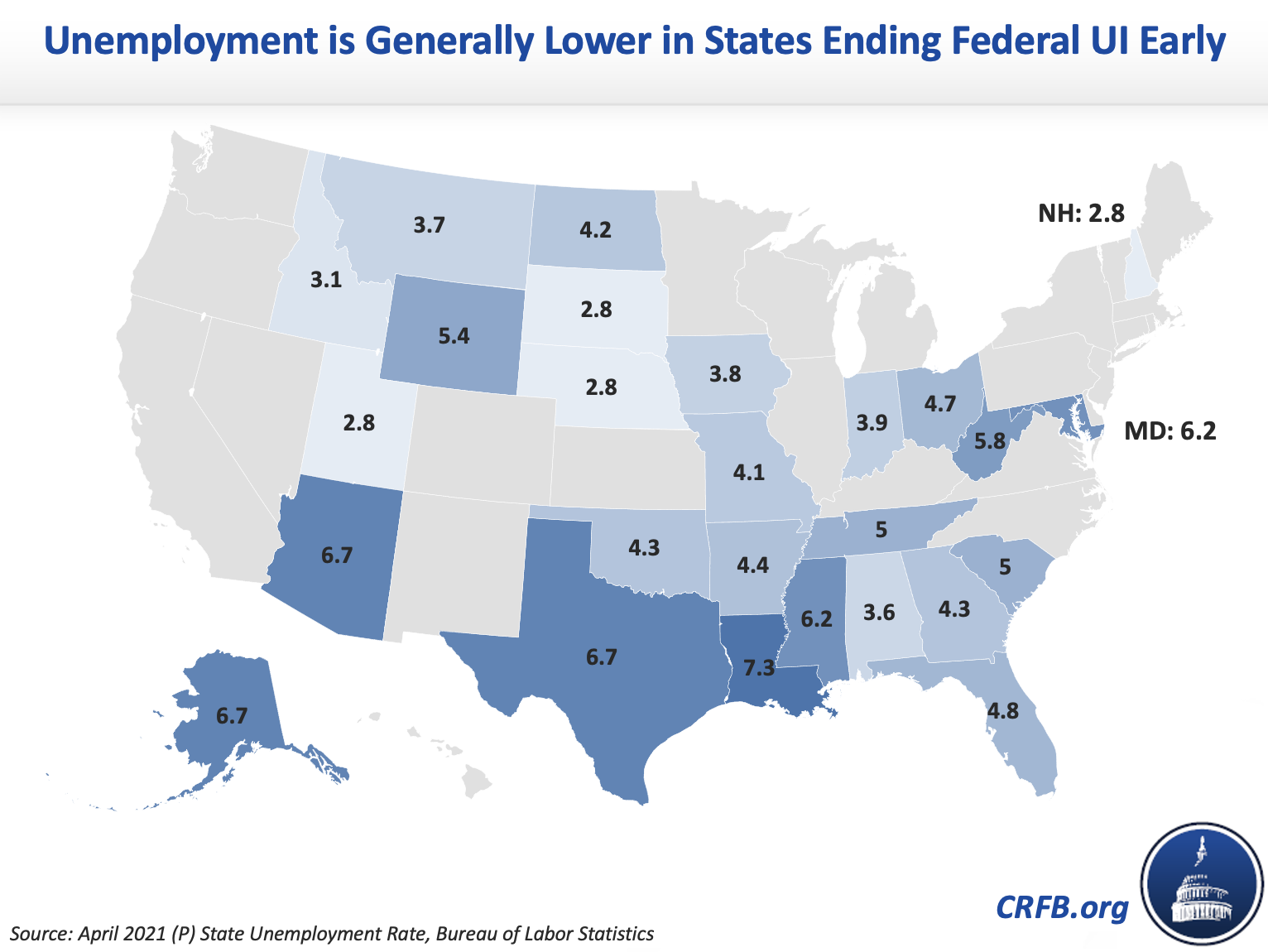

Many of the states terminating benefits early have cited labor shortages as the primary reason for the decision, although unemployment rates in most of these states are lower than the national average. In fact, two states that have announced a premature end to federal UI expansions – Nebraska and South Dakota – had lower unemployment rates in April of 2021 than in February of 2020, prior to the onset of the COVID pandemic.

There are signs of tightness in the labor market overall, however. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were approximately 9.3 million job openings in April – 2.3 million more than in February 2020 and significantly more than there would otherwise be given the pre-COVID Beveridge Curve.4 Furthermore, average wages grew by 0.6 percent in May (7.2 percent at an annual rate), making it the strongest month for wage growth since the early 1980s. While this could be a sign of rising productivity and greater worker bargaining power, it is more likely a reflection of some sectoral labor supply shortages.

Thus far, the 26 states ending federal unemployment benefits early have received over a quarter of the payments made under extensions of federal unemployment benefit expansions included in the American Rescue Plan, in terms of dollars. This is in part due to the population of these states as a share of the national total, and partly due to lower overall unemployment rates in these states.

The national unemployment rate in April was 6.1 percent, whereas the average unemployment rate of the states ending federal unemployment benefits early was 4.7 percent – 1.4 percentage points lower. Only six out of the 26 states – Alaska, Arizona, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, and Texas – had unemployment rates higher than the national unemployment rate in April.

Personal income has been boosted considerably by COVID relief since last April – thanks in no small part to expanded UI. Ending the federal UI expansions early will inevitably mean a significant reduction to this boost to personal income. However, the overall effect on personal income could be negative or positive depending on whether the early terminations result in more employment in the aggregate and, as a result, higher market income. Some states – including Arizona and Montana – are also offering return-to-work bonuses to compensate for the loss of expanded benefits.

Ending federal unemployment benefit expansions earlier than scheduled creates a cliff edge benefit cut particularly for those receiving unemployment through the PUA and PEUC programs, which is not ideal policy. Had benefits been linked to economic triggers such as state unemployment rates, or phased-down over time, perhaps states would not have acted unilaterally to end benefits early.

This blog post is a product of the COVID Money Tracker, an initiative of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget focused on identifying and tracking the disbursement of the trillions being poured into the economy to combat the crisis through legislative, administrative, and Federal Reserve actions.

1 Alaska is only terminating Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (i.e. the additional $300 payment per week to unemployed persons) early. Federal unemployment benefits for self-employed (Pandemic Unemployment Assistance) and persons who have exhausted regular benefits (Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation) will continue in the state through their scheduled expiry under the American Rescue Plan.

2 The vast majority of the cost of federal UI in the American Rescue Plan is from the three major programs, but there are other federal UI assistance programs that were continued or reauthorized by the legislation, including Mixed Earner Unemployment Compensation (MEUC), 100 percent federal funding of Extended Benefits and Short-Time Compensation, temporary full funding of the first week of UI benefits in states that waive waiting weeks, and partial (75 percent) reimbursement of UI benefits paid by government/tribal entities and non-profits.

3 Four states — Alaska, Arizona, Florida, and Ohio — are only terminating FPUC early.

4 The Beveridge Curve plots the job opening rate against the unemployment rate, with higher job opening rates associated with lower unemployment levels, and vice versa. The current job openings rate would not usually be this high given the current unemployment rate, and even though the curve tends to shift out during economic recoveries, the scale of the outward shift potentially signals a significant disconnect between the supply and demand of labor at least in the short-run.