The Mortgage Interest Deduction Should Be on the Table

As efforts for tax reform continue, there will be plenty of discussion about which tax breaks should be retained and which should be reduced or eliminated. We have already discussed reasons why eliminating the state and local tax deduction, as the unified framework for tax reform does, is worth considering. Another major tax break is the mortgage interest deduction (MID).

The framework does not directly reduce or eliminate the deduction, though it significantly reduces its value indirectly by increasing the standard deduction, eliminating other itemized deductions, and reducing tax rates. The framework did seem to leave open the possibility of a direct reform. Regardless, it would be a mistake to retain the deduction as is, since it is expensive, regressive, ineffective, and economically distorting, and there are many options for reform.

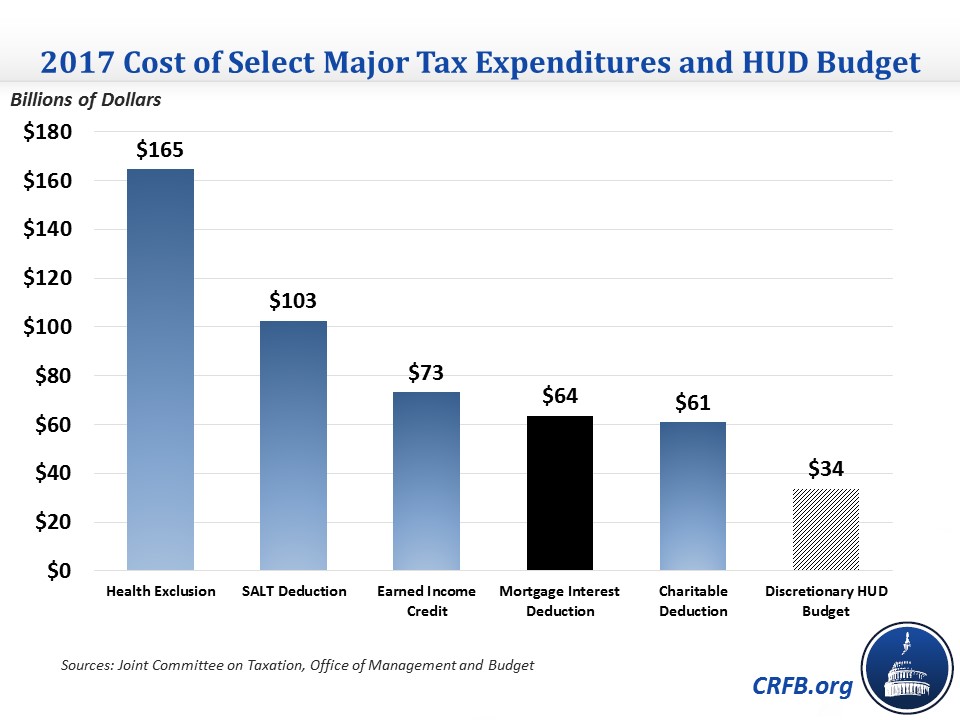

The mortgage interest deduction is expensive and is among the largest tax expenditures in the tax code. Despite the cap on the deduction to apply only to the interest on the first $1 million of a mortgage and the first $100,000 of a home equity loan, it still cost $64 billion in 2017 according to the Joint Committee on Taxation. This amount is almost double the entire discretionary budget for the Department of Housing and Urban Development, even before considering other housing tax breaks like the property tax deduction and the $500,000 exclusion for gains on home sales.

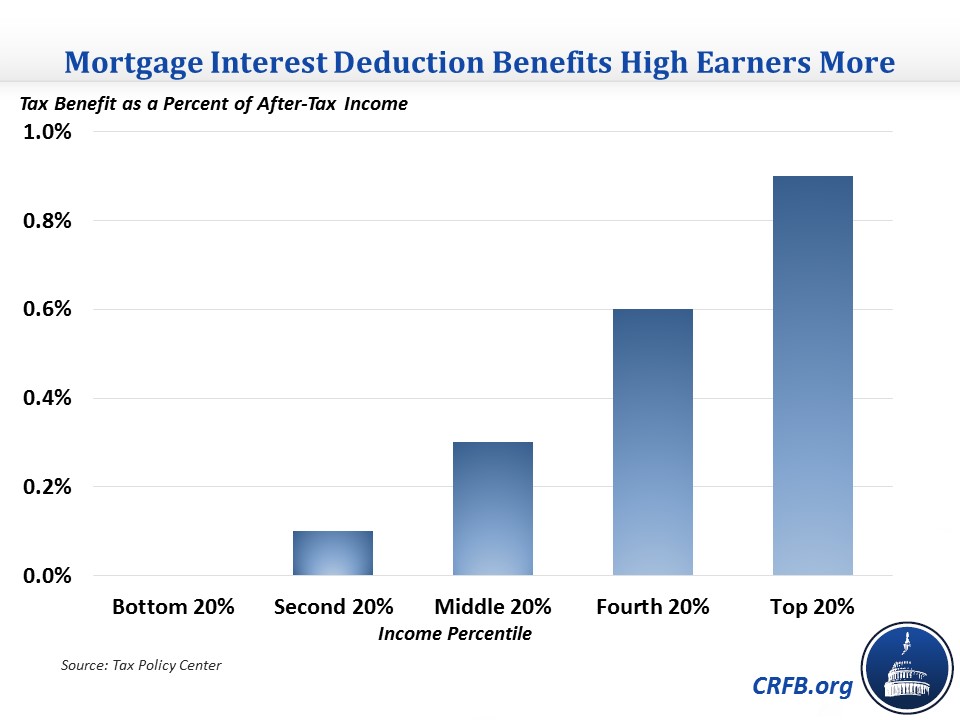

The mortgage interest deduction is regressive, providing larger benefits to higher-income taxpayers. In particular, it benefits those in the 80-99th percentiles of earnings; those in top 1 percent tend to benefit less since the existing cap on the deduction limits their benefits relative to income.

The deduction is regressive for several reasons. First, only one-fifth of taxpayers take the deduction because relatively few taxpayers itemize their deductions; 70 percent of those in the top fifth do while almost none of the bottom 40 percent do. Second, high-income people are more likely to buy homes and more likely to buy expensive homes that take fuller advantage of the deduction. Finally, the value of deductions rises with marginal tax rates, which are higher for those with higher incomes: someone in the bottom tax bracket only gets a 10-cent subsidy for $1 of deductions while someone in the top bracket gets 39.6 cents. These factors mean that the MID provides almost no benefit to the bottom 40 percent, a 0.3 percent of income benefit to the middle fifth of earners, and a 0.9 percent benefit to the top fifth.

According to estimates from the Tax Policy Center, the top fifth of earners receive nearly three-quarters of the benefit of the deduction, while the top tenth of earners receive half percent of the benefit.

The mortgage interest deduction is ineffective at accomplishing its goal of promoting homeownership. Other developed countries with no mortgage interest deduction have similar or higher homeownership rates. Several studies have shown, both in the U.S. and in other countries, that the mortgage interest deduction doesn't increase the rate of homeownership. These findings are perhaps not surprising given the fact that most of the benefit of the deduction goes to higher earners who would likely buy a home regardless of any tax incentives. It would be possible that a better-targeted incentive for homebuyers would be more effective, but it would have to take a different form than the current deduction.

On a related note, the mortgage interest deduction creates economic distortions. The deduction doesn't subsidize homeownership as much as it subsidizes debt. The economic literature has generally found that rather than increasing homeownership, the mortgage interest deduction encourages people to buy bigger homes and by taking on more debt. Several studies show using natural experiments that the willingness of homeowners to take on debt is sensitive to the tax benefits they receive, so the mortgage interest deduction causes homeowners to overleverage rather than using their funds for more economically productive purposes. This mechanism drives up housing prices, making it harder for new homebuyers to get into the market. The deduction also advantages homebuyers over renters since renters don't have a similar deduction at the federal level. Finally, as we saw ten years ago, overleveraging housing debt can have severe economic consequences.

Finally, there are many options to reform the mortgage interest deduction. Short of eliminating the deduction by gradually reducing the limit on deductibility to zero, there are several options to reform the deduction. Policymakers could gradually reduce the limit to a lower level, which would reduce the incentive to buy larger and more expensive homes, or limit the value of the deduction to a certain tax rate. They could also convert the deduction to a non-refundable or refundable tax credit, which would not only reduce the benefit for high earners but also provide a benefit for homeowners who don't currently itemize and potentially make it more effective at promoting homeownership. There are also smaller reforms to the deduction available like eliminating it for second homes, yachts, and late payment penalties. Any of these policies would help make the deduction fairer and less regressive.

For all of these reasons, several major tax reform plans have proposed to reform the mortgage interest deduction. The 2005 President's Advisory Panel on Tax Reform, the Simpson-Bowles illustrative tax plan, and the Domenici-Rivlin Debt Reduction Task Force Plan all proposed converting the deduction to a credit, though with different details. The 2005 President's Advisory Panel would have created a 15 percent credit with the size of the limited to the average regional housing price, Simpson-Bowles would have had a 12 percent credit limited to mortgages of $500,000, and Domenici-Rivlin would have had a 15 percent credit limited to $25,000 of interest expense. Former Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp's Tax Reform Act of 2014 would have gradually reduced the deduction limit from $1.1 million to $500,000 over four years. President Obama also proposed limiting the value of the deduction to 28 percent, which would reduce its value for taxpayers in the top three tax brackets.

Though the Big 6 framework has proposed to eliminate some tax breaks, like the state and local tax deduction, it has not thus far proposed direct changes to the mortgage interest deduction. Reforming it should be on the table, especially if the state & local tax deduction is retained in some form. There are many good reasons why the deduction should be reformed and scaled back, and doing so can help the framework become more fiscally responsible.