MedPAC's Prescriptions for Medicare

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has released its June 2012 report, detailing ways in which Congress can improve Medicare to better control costs and improve care.

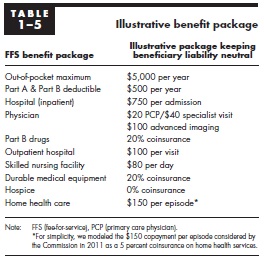

For budgeteers, the first chapter is a particularly helpful portion of the report, discussing Medicare's cost-sharing strucuture. MedPAC finds a number of issues with the structure that could be changed for the better. They note that there is no out-of-pocket maximum for cost-sharing, there are two separate and very different deductibles for Parts A and B, and the benefit design utilizes coinsurance more frequently than copayments despite the fact that copayments provide more predictable cost-sharing for beneficiaries. In addition, many beneficiaries have supplemental "first-dollar" coverage, which often shields them from the effects of cost-sharing, leading them to use perhaps unnecessary care (at least more than they would otherwise). As a result, they say:

In summary, the Commission believes that a new FFS benefit design should include:

- an OOP maximum (measured in cost-sharing liability incurred by the beneficiary) to protect beneficiaries from the financial risk of very high Medicare costs;

- deductible(s) for Part A and Part B services that may be combined or separate;

- copayments, rather than coinsurance, that may vary by type of service and provider;

- secretarial authority to alter or eliminate cost sharing based on the evidence of the value of services;

- no change in beneficiaries’ aggregate cost-sharing liability; and

- an additional charge on supplemental insurance to recoup at least some of the added costs imposed on Medicare.

They do not make specific recommendations, but they design an illustrative cost-sharing plan that would be deficit-neutral in terms of primary effects. However, the secondary effect of the cost-sharing on Medicare spending could have lowered spending by between 0.5 and 4 percent in 2009, based on how many people kept their supplemental coverage. In terms of distribution of the proposal, 70 percent of beneficiaries would see only a minor change, but about 20 percent of beneficiaries would see a greater than $250 annual increase in cost-sharing while 9 percent would see a greater than $250 decrease.

Obviously, adjustments could be made to make it a deficit-reducing package in terms of primary effects, as some major budget plans have done. For example, the Simpson-Bowles plan followed the MedPAC illustrative plan in having an out-of-pocket maximum (although it was higher) and restricting the amoun of cost-sharing that Medigap plans could cover, but it relied more on coinsurance than copayments varying by service. (For more on the Simpson-Bowles cost-sharing reforms, click here.)

Other chapters of the report deal more with health care delivery. The second chapter details the lack of care coordination within fee-for-service Medicare, while the third chapter deals with lack of coordination between Medicaid and Medicare with regards to "dual eligibles" (people who are eligible for both programs). Two other chapters deal with how to improve risk adjustments for payments in Medicare Advantage (Part C) and how to improve Medicare for rural beneficiaries.

Considering the importance of health care spending, especially Medicare, in our budget future, improving Medicare's cost-sharing structure and delivery system will be crucial. The full MedPAC report is well worth the read.