A Look at Medigap Reforms

The Washington Post had an editorial yesterday supporting efforts to restrict first-dollar coverage for Medigap. Medigap is a form of private, supplemental coverage that Medicare beneficiaries can purchase on top of traditional Medicare to help cover costs, and about one-sixth of Medicare recipients. It's encouraging to see continuing public debate on ways to go further on trying to control health care costs, and Medigap reforms can be a good place to look.

The editorial specifically mentions the Fiscal Commission's recommendation on Medigap reform, which would prohibit supplemental plans from covering the first $500 of cost-sharing and 50 percent of the next $5,000; this change would save $53 billion over ten years. In conjunction with this change, they would simplify Medicare's cost-sharing rules and introduce a new out-of-pocket limit for total cost sharing. Also, the editorial mentions President Obama's Medigap reform, which would impose a premium surcharge starting in 2017 on Medigap plans that had first-dollar coverage; this would save only $2.5 billion.

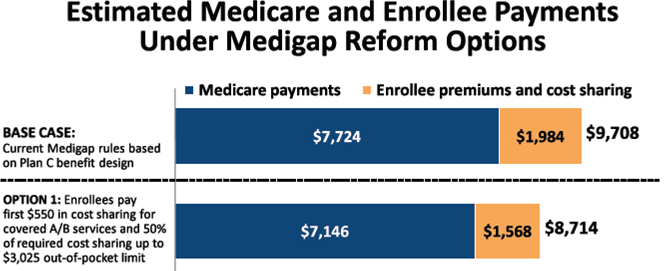

Reforming Medigap policies not only makes sense for reducing overall Medicare spending, but also when considering beneficiaries' costs. A Kaiser Family Foundation study that looked at a proposal very similar to the Commission (one with a lower out-of-pocket limit) found that total beneficiary cost-sharing would actually go down on average. Because Medigap policies would be restricted on how much they could cover, seniors would pay significantly less premiums for Medigap policies. Kaiser finds that these savings would outweigh the increased cost-sharing for about 80 percent of current Medigap users, by an average of $415 (or about a 20 percent reduction), and a majority of Medigap users (57 percent) would see savings of more than $500. Since many seniors do not utilize Medicare much in a given year, they would on average not face as much increased cost-sharing as they would decreased Medigap premiums.

The graph below is reproduced from Kaiser's report, which shows both the average per-person Medicare and beneficiary savings.

Of course, this reform is not painless. Among the minority of those who would pay more, they would more frequently be in poorer health and of more modest income. The Kaiser Foundation study estimated that approximately one-third of beneficiaries in low health and one-quarter of beneficiaries with low incomes would face increases in out of pocket expenses that exceed their savings from lower Medigap premiums. Of course, this means that the large majority of beneficiaries with poor health or modest incomes would see net savings from this policy.

However, distributional effects can be addressed in other parts of a comprehensive Medicare reform plan or overall fiscal plan. For example, the Social Security reform plan proposed by the Fiscal Commission would establish a new minimum benefit and an old-age bump up that would benefit seniors most likely to be negatively impacted by this policy. Overall, a Medigap reform along the lines of the Fiscal Commission plan or the Lieberman-Coburn proposal makes sense as a way to make Medicare spending more sustainable over time.

Note: This blog has been updated since its original posting.